Thorpe Affair UK Parliamentary Scandal

ThorpeAffairUKParliamentaryScandal

'A Very English Scandal': The Real Story Of Jeremy Thorpe, Norman Scott And The Alleged Murder Plot That Rocked British Politics

Jeremy Thorpe scandal: Suspect might not be dead, police say

The BBC is bringing to life one of the biggest stories to ever rock British politics on Sunday (20 May) night with big-budget drama ‘A Very English Scandal’.

Starring Hugh Grant and Ben Whishaw, it tells the tale of the Thorpe scandal back in the 1970s, which saw MP Jeremy Thorpe stand trial for conspiracy to murder his former lover, Norman Scott.

The three-part series is based on John Preston’s true-crime non-fiction novel of the same name, and the script has been penned by esteemed writer and former ‘Doctor Who’ boss Russell T. Davies, with ex-‘EastEnders’ head honcho Dominic Treadwell-Collins serving as executive producer.

“It’s a great story and is tabloid-y and it’s funny and sensational, but actually these are real people. This really happened,” Russell says. “The fascinating story, the consequences and the ramifications of this go on through the decades.”

But for those not old enough to remember what happened, we took a look at the story that shocked the nation...

Who was Jeremy Thorpe?

Jeremy Thorpe was a former leader of the Liberal party who took office in 1967, but he is now better known for being the first politician to ever stand trial for conspiracy to murder.

He was born in 1929 into a Conservative family, but after studying at Eton and Oxford, he found his political ideas aligned more closely with the Liberal party. His career as a Liberal MP began in 1959 when he was elected to represent the North Devon constituency.

After taking over as leader, the once-struggling party saw its popularity soar, and by 1974, it seemed as if they stood a chance at being voted into power.

However, Thorpe was hiding the truth about his sexuality, as he had enjoyed relationships and liaisons with men, despite being twice married - first to Caroline Allpass, who died in a car crash in 1970, and then to Marion Stein from 1973.

His double life was hugely risky, as it was illegal to be homosexual in Britain until 1967, and even after the law changed, Thorpe believed the truth being uncovered would put an instant end to his political career.

One man who he’d had an affair with long before taking over as leader of the Liberal party and the decriminalisation of homosexuality, was a man named Norman Scott...

Who is Norman Scott?

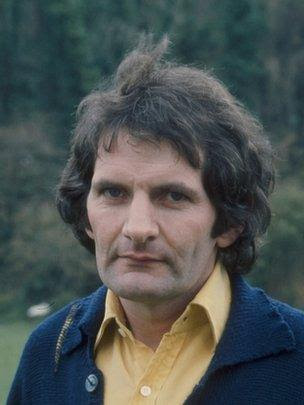

Norman Scott was an accomplished horseman and one-time model, who was working as a groom at the stables of the self-made son of a coalminer, Brecht Van de Vater, in the early 1960s.

During this time, Thorpe paid a visit to the stables and took a shine to him. He told Scott - then going by the name of Norman Josiffe - if he ever experienced problems with his employer to get in touch.

Months later, Scott left the stables after a row with Vater and suffered a mental breakdown, spending time in a psychiatric hospital for his severe depression.

Having been estranged from his family years prior, upon his release from hospital, Scott found himself penniless and homeless. He had also left Vater’s employment without a National Insurance Card, which he needed to be able to claim work and access to benefits. It was then he contacted Thorpe for help...

How did Jeremy and Norman’s affair begin?

According to Scott’s testimonial in court, after visiting Thorpe for assistance, he was taken to the house of his wealthy mother, Ursula, in Oxted. He claimed that during the night, Thorpe slipped into his room and the pair had sex for the first time.

A relationship soon ensued, and Thorpe showered Scott with gifts, paid his rent and tried to help him find work. He also acted as his guardian in 1962 when he was questioned about the theft of a leather jacket from the psychiatric hospital he was treated at.

Thorpe soon assumed the role of his employer, but their relationship soured by later that year, with Scott claiming Thorpe had retained his replacement National Insurance Card. This remained an on-going source of tension between them.

Thorpe always maintained he and Scott did not have a relationship and he had never employed him, stating they had only ever been friends.

What happened to Scott after the affair?

Suffering another spell of depression, Scott confided in a friend he wanted to shoot the MP and commit suicide. This friend told the police, and Scott was forced to provide letters between him and Thorpe proving their affair. However, it was not enough for them to take any action.

He spent the ensuing years moving around, while finding it difficult to find stable employment thanks to the missing National Insurance Card. He blamed Thorpe for his troubles, regularly attempting to contact him for help.

He had, however, briefly married a woman in 1969, and fathered a son who he became estranged from.

Meanwhile, Thorpe had washed his hands of the affair, and enlisted fellow MP Peter Bessell to help sort the situation with Scott.

But with his regular demands, Scott remained a threat to Thorpe’s reputation.

What is alleged to have happened next?

In the ensuing court case, the prosecution alleged that in 1969, Thorpe tried to persuade Bessell and friend David Holmes to kill Scott.

While initially they rejected the idea, years later, it is claimed Holmes began recruiting for a hit man, who was eventually found in the form of an airline pilot called Andrew Newton.

In October 1975, a plot was allegedly set up where Newton - calling himself Peter Keen - drove to Barnstaple and approached Scott telling him to get in his car as he had been hired to protect him from a suspected hit man.

What Newton hadn’t anticipated was that Scott would have his dog with him - an animal he was terrified of.

They stopped at a pre-determined point, but as Scott got out of the car, he was followed by his Great Dane, so Newton shot her. He then turned the gun on Scott, but the pistol failed several times and he rode off into the night.

Newton was later arrested after police found Scott, but insisted he had only ever been hired to intimidate Scott, although he did not reveal whose orders he was following. He was later convicted and sent to prison.

How did details of their affair come out?

While many newspapers knew of Thorpe’s liaisons with men, they were not able to publish the details, being wary of libel.

However, the claims about their relationship came to light when Scott appeared in a magistrates court on an unrelated minor social security fraud charge, where he stated he was being hounded over his and Thorpe’s romance.

As the claims were made in court - and therefore safe from libel laws - this meant newspapers were able to publish them, and the story became front page news.

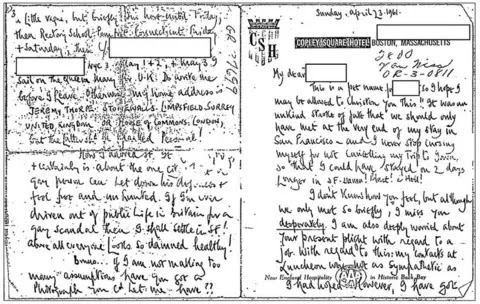

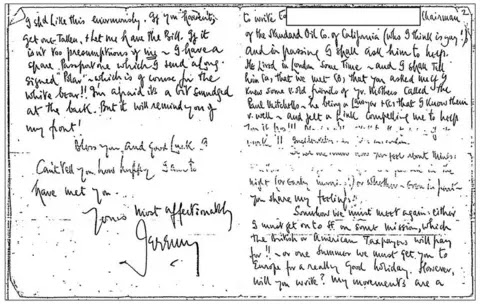

Thorpe tried to quash the story by publishing what he claimed was a platonic letter he’d sent to Scott in 1962, but his use of his pet name “Bunnies” raised suspicion he was not telling the truth.

Under increasing pressure, Thorpe was forced to step down as leader of the Liberal party in May 1976. However, he still maintained they had not had a romantic relationship, explaining how he was quitting because of the damage the story had caused the party.

While press coverage died down, things blew up again when Newton was released from prison in October 1977 and he sold his story to the press, claiming he had been paid to kill Scott.

Thorpe, Holmes and two other men involved in hiring Newton were arrested and charged with conspiracy to murder. Thorpe was additionally charged with incitement to murder, due to his initial meetings in 1969 with Holmes and Bessell. The former MP maintained his innocence and vowed to clear his name when the case went to trial.

What happened at the trial?

The trial began at the Old Bailey on 8 May 1979 under Judge Joseph Cantley.

Thorpe, Holmes and one of the other two men did not testify in court, choosing to remain silent, believing the testimonies of Scott, Newton and Bessell did not make a good case for the prosecution.

Thorpe’s lawyer, George Carman, had also managed to paint the trio as untrustworthy and amoral, and in his closing speech, he suggested Holmes and others might have organised a conspiracy to kill Scott without Thorpe’s knowledge.

Over a month later on 20 June, the jury retired.

They returned to court after just two days, acquitting all four men of all charges, noting that Thorpe, a man of “hitherto unblemished reputation” and “a national figure with a very distinguished public record” could not be capable of the crime.

Judge Cantley also branded Scott a “crook, liar and parasite” following the verdict.

What happened to Thorpe after the trial?

Despite being found not guilty, Thorpe’s reputation was left in tatters after the trial and it never recovered. He did not return to politics, although he was appointed a director of Amnesty International in 1982, but staff protested and he withdrew from the position.

Shortly after, he first started showing signs of Parkinson’s Disease - a condition that gradually worsened over the ensuing years.

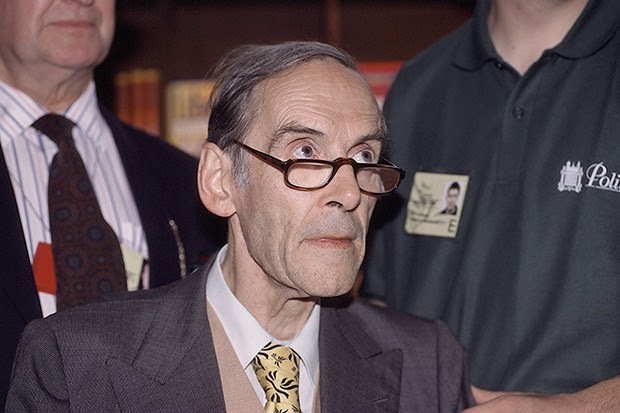

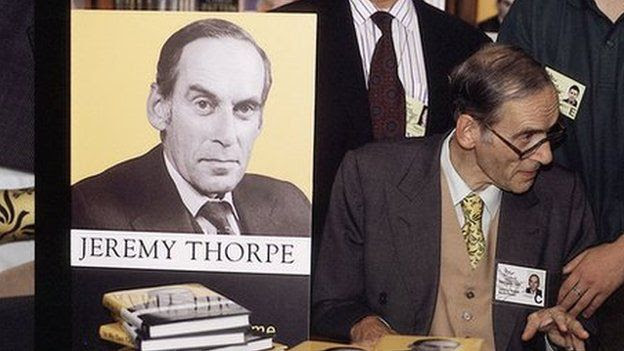

In 1999, after years away from public life, he published his memoirs, In My Own Time, in which he justified his silence at the trial and stated he never doubted the outcome.

Nine years later, he gave his first press interview in 25 years to The Guardian, where he said of the affair: “If it happened now I think the public would be kinder. Back then they were very troubled by it ... It offended their set of values.”

His health declined further declined, and he was cared for by his wife Marion until her death in March 2014.

Thorpe lived for a further nine months after her death, dying on 4 December 2014 at the age of 85.

What happened to Scott after the trial?

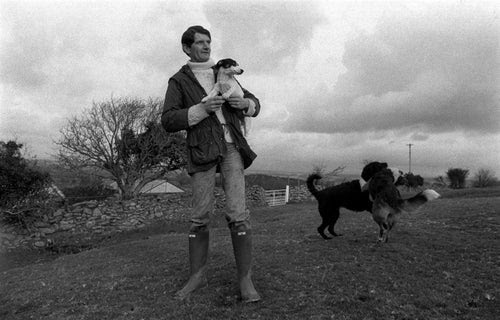

Now 78, Norman Scott has been in a happy relationship for 20 years, and lives in a Devon farmhouse. He has always maintained Thorpe wanted him dead.

In an interview published in The Times last month, he said: “I think he should have gone to prison. And that also would have made my life so different, because people would have believed me.”

‘A Very English Scandal’ begins on Sunday 20 May at 9pm on BBC One.

Jeremy Thorpe scandal: Suspect might not be dead, police say

https://www.bbc.com/news/uk-

2 June 2018

A probe into a scandal involving former Liberal leader Jeremy Thorpe is to be revisited, after police admitted that a key suspect may still be alive.

A 2015 investigation into the alleged attempted murder of Mr Thorpe's lover - Norman Scott - was closed in 2017.

Gwent Police believed Andrew Newton - who claimed he was paid to kill Mr Scott - had died. But the force has now told the BBC this may not be the case.

Mr Scott said he thought police were continuing a "cover-up".

The revelations have been made in the BBC Four documentary The Jeremy Thorpe Scandal.

Following the BBC's revelations, the Mail on Sunday said it had tracked down Mr Newton - living under a different name - in Surrey.

The paper has published what it claims is a picture of Mr Newton, taken on Saturday. The man's face cannot be seen.

New information

Mr Thorpe, who died in 2014, was accused of hiring a hitman to murder Mr Scott but was acquitted at an Old Bailey trial in 1979.

The fresh investigation was launched by Gwent Police in 2015 after new claims emerged.

But the police's belief that Newton - who was convicted of shooting Mr Scott's dog in 1975 - had died, led the Crown Prosecution Service to close it last year.

Gwent Police told documentary makers enquiries made as part of the investigation had "indicated Newton was deceased".

But they added: "We have now revisited these enquiries and have identified information which indicates that Newton may still be alive."

The force said it planned to assess if Mr Newton "is able to assist the investigation".

When asked on Saturday night about the Mail on Sunday's claims to have tracked Mr Newton to Surrey, Gwent Police said it had "lines of inquiry open" but would not provide further comment "at this time".

What was the Jeremy Thorpe scandal?

What was the Jeremy Thorpe scandal?

- Jeremy Thorpe was the MP for North Devon for 20 years, and leader of the Liberal Party between 1967-76. He died in 2014

- He was offered a cabinet post after the February 1974 election by then-Prime Minister Edward Heath

- In late 1960 or early 1961 he met Norman Scott, who worked for one of Mr Thorpe's friends in Oxfordshire. Mr Scott said the two were lovers, at a time when homosexuality was illegal

- Mr Scott spent years attempting to reveal the pair's relationship to the public, then claimed Mr Thorpe conspired with colleagues to have him assassinated

- In 1975, Andrew Newton shot Mr Scott's Great Dane, Rinka, on a rural road in Exmoor, but failed to kill Mr Scott after his gun jammed

- Newspapers began reporting Mr Scott's claims after he spoke about the relationship in court, meaning they were protected from libel laws

- Mr Thorpe resigned as leader of the Liberal Party in 1976 over the reports, but denied Mr Scott's allegations. He lost his seat in North Devon in 1979

- Mr Thorpe, along with three co-defendants, stood trial. Ex-Liberal MP Peter Bessell, and the failed assassin Newton, gave details of the alleged plot. A jury acquitted all four in 1979

BBC Panorama journalist Tom Mangold, who has investigated the case since the 1970s, said the 2015 investigation hinged on the story of a man he had met called Dennis Meighan.

Mr Meighan told the veteran reporter he was originally approached to carry out the murder - but he claims his police statement was later doctored to remove incriminating references to the Liberal Party and to Mr Thorpe.

Following Gwent Police's admission that Newton could still be alive, Mr Mangold insisted the investigation "must start again".

And reacting to the news, Mr Scott, 78, told the documentary: "I just don't think anyone's tried hard enough to look for him. I really don't.

"There must be people who knew him and there would surely be a record of him dying.

"I thought [Gwent Police] were doing something at last, and soon found out that absolutely they weren't, they were continuing the cover up as far as I can see."

The programme includes unearthed footage from a Panorama programme from 1979 that was never broadcast for legal reasons, after Mr Thorpe and his three co-defendants were acquitted of conspiracy to murder.

The director general at the time kept a master copy of the programme but ordered all other copies to be destroyed. But journalist Tom Mangold kept his copy of the report.

The programme will air after the end of the dramatisation A Very British Scandal, which stars Hugh Grant as Jeremy Thorpe and Ben Whishaw as Norman Scott.

A Very 'bone-chilling' English Scandal

Hugh Grant, politics and a murdered dog

Revealed: Letter that silenced Thorpe

Obituary: Jeremy Thorpe

How accurate is A Very English Scandal? What's the true story and who was Jeremy Thorpe? BBC1, BBC First | Radio Times

The real history behind A Very English Scandal and the Jeremy Thorpe affair

Hugh Grant and Ben Whishaw star in Russell T Davies' new show about the first British politician to stand trial for murder – but what is the truth behind the drama?

Russell T Davies's new drama A Very English Scandal is adapted from the "non-fiction novel" by John Preston and tells the true story of the 1970s Thorpe affair, in which former Liberal Party leader Jeremy Thorpe was accused of conspiring to murder his alleged former lover Norman Scott.

Who was Jeremy Thorpe MP?

Jeremy Thorpe was the first British politician to stand trial for murder.

He was leader of the Liberal Party from 1967 until 1976, when revelations about a homosexual relationship with former model Norman Scott and an alleged murder plot came to light. He was tried and acquitted at the Old Bailey after one of the most notorious judgements in the court's history.

Born in 1929, he came from a line of Conservative MPs, but his political ideas aligned with the small and struggling Liberal Party and he set his sights on becoming a Liberal MP. After Eton and Oxford and a few years working in law and television, Thorpe was elected to Parliament for North Devon and became a rising star in the Party. Eight years later he had manoeuvred his way to the top and became the Leader.

Was Jeremy Thorpe homosexual?

Thorpe had many relationships and liaisons with men, but this was a hugely risky secret life: all homosexual activity was illegal in the United Kingdom until 1967, and the truth about his sexuality would have instantly ended his political career.

More like this

Meet the cast of A Very Royal Scandal

He was married twice, first to Caroline and then – when she died in a car crash – to the formidable Marion. On his first wedding, he reportedly told his friend Bessell: "If it's the price I've got to pay to lead this old party, I'll pay it."

Long before he was married and before homosexual activity was decriminalised, Thorpe had a short-lived affair with a man named Norman Scott (then known as Norman Josiffe). This would haunt him for the rest of his career.

Who was Norman Scott and what was his relationship with Jeremy Thorpe?

In 1961, Norman Scott had been suffering from severe depression and was fresh out of a psychiatric hospital. He was 21 and penniless, estranged from his mother, unknown to his father, and working as a groom at the stables of Brecht Van de Vater. It was while visiting his pal Vater that Jeremy Thorpe met Scott for the first time.

It was a chance encounter that would change the direction of his life.

Thorpe had urged Scott to get in touch if there were any problems with Vater as his employer, and sure enough, problems soon arose. Scott went to see his political friend in a state of great distress.

That same night he and his beloved Jack Russell Mrs Tish were taken to the house of Thorpe's wealthy mother Ursula. During the night, Thorpe slipped into Scott's room and – according to Scott's testimony – had sex with him for the first time. Thorpe nicknamed his new lover "Bunnies".

Scott had no money or prospects, but Thorpe paid his rent and bought him expensive new clothes and introduced him to friends. When the police questioned Scott about the alleged theft of a suede jacket from a fellow former patient of the psychiatric hospital, Thorpe insisted on acting as his guardian and seeing off the threat of legal action. But the relationship soon soured.

Why was Norman Scott a problem?

Over the next 15 years, Scott found employment here and there, moving around the country and trying out everything from modelling to monasteries. He had a disastrous and brief marriage, and fathered a son who he was barely allowed to see. He often lived in poverty, and went through periods of severe mental illness, attempting suicide.

Frequently he appealed for financial and practical help from Thorpe, who he blamed for his troubles: the MP had kept (and possibly lost) his National Insurance card, which was absolutely vital for him to get a job or benefits.

Thorpe washed his hands of the affair as much as possible, instead turning to his friend and admirer Peter Bessell MP to clean up his mess.

One particular mess came when Scott casually mentioned to Bessell that he'd lost his suitcase somewhere in Switzerland, containing several letters that Thorpe had written to him. The suitcase was hastily located and sent to the British Consulate in Zurich, where it was forwarded to Victoria station in London. Thorpe went along with Bessell's secretary Diana Stainton to collect it – with an ulterior motive: as she looked on in horror, he grabbed the case, forced open the locks and extracted the incriminating letters before sending it on to Scott in Dublin.

But the problem refused to disappear. Scott remained a threat to the politician's reputation – so Thorpe decided to do something about it.

What was Jeremy Thorpe alleged to have done?

"The higher he climbed on the political ladder, the greater was the threat to his ambition from Scott," the prosecution lawyer began at Thorpe's 1979 trial. "His anxiety became an obsession and his thoughts desperate."

The prosecution alleged that, early in 1969, Thorpe had invited his colleague Bessell and friend David Holmes to his room at the House of Commons, where he tried to persuade Holmes to kill Scott. Both men were pretty taken aback. For the next few years they humoured him, tried to dissuade him, and suggested alternatives. But the idea of murdering Scott never went away.

Bessell was having his own difficulties and left the country, but Holmes was finally convinced. He began a farcical attempt to recruit an assassin, enlisting the help of a dealer in carpets and a dealer in fruit machines. The men tracked down an airline pilot called Andrew Newton who, after 16 pints, agreed to kill Scott for £10,000. The money was funnelled away from the Liberal Party election funds.

Newton's nickname was "chicken-brains" and his initial plan, as he testified in court, was to attack his victim with a chisel hidden inside a bouquet of flowers. His eventual plan involved a gun – but didn't go any more smoothly.

In October 1975, pretending he'd been sent to protect Scott from a would-be killer, Newton persuaded him to get into his car. But Scott insisted on bringing along his giant Great Dane Rinka. Newton was terrified of dogs.

When Newton pulled over in the Exmoor fog and jumped out at a pre-determined spot, there was a complication: the excited hound apparently thought she was going for a walk and clambered out alongside Scott. So Newton shot her to death. He then turned the gun on Scott, but it did not go off and Scott scrambled away. (Newton later claimed he'd never intended to kill his victim, just to frighten him.)

The hapless gunman was caught and sent to prison for a couple of years for destruction of property (Rinka) and for intent to endanger life. Still, Scott's testimony about Jeremy Thorpe – and the ludicrous idea of a murder plot – was laughed out of court.

When – and how – was homosexuality legalised?

In 1957, the Wolfenden Report had recommended that "homosexual behaviour" between consenting adults in private should no longer be criminalised, but it was some time before Parliament was ready to consider the issue in earnest.

One politician who was determined to change the law was a Welsh Labour MP called Leo Abse. Unfortunately, despite his best attempts, in the early 1960s he was getting nowhere: the Lord Chancellor Lord Kilmuir refused to sit in any Cabinet meeting where the "filthy subject" would be discussed. What Abse needed was an ally in the Lords.

In 1965 he went to see the eighth Earl of Arran, known to friends as "Boofy". Lord Arran and his wife were utterly obsessed with badgers. At their home in Hemel Hempstead badgers were given the run of the place, so all humans were advised to wear gumboots and watch out for ringworm. But aside from badgers, he was also passionate about homosexual law reform – for undisclosed reasons.

It wasn't until later that Abse learned that Boofy's elder brother had been gay, and had killed himself.

The bill made steady progress through Parliament, but was sidelined when the Prime Minister called a general election; Abse and Arran persevered and managed to get it back on the table once a new government was formed. The Sexual offences Act was passed in 1967.

How did the Jeremy Thorpe affair come to light?

Up until this point, Thorpe had mainly kept rumours about his sexuality and his relationship with Scott under wraps, with the help of political colleagues, a compliant press, friends like Bessell, and the police. But in December 1975 the Private Eye and the Sunday Express caught on to a story from the local press about the mystery of the "dog in the fog".

As Preston writes, "in the tea rooms and corridors, people began to talk. And, as the gossip swirled, so did half-remembered rumours from years before."

The press started to dig, finding out that Thorpe's men had paid thousands to buy back potentially incriminating letters. Statements were made by Holmes and Bessell and Scott and Thorpe and the whole messy story began to emerge. Old letters between Thorpe and Scott were published in the newspapers, showing their once-affectionate relationship: "Bunnies can (and will) go to France," the MP wrote to his young lover. No one quite knew what it meant.

Thorpe was forced to resign his leadership of the Liberal Party in 1976. In 1978 he was arrested and charged, alongside Holmes and two other men: the carpet dealer and the fruit machine dealer who had allegedly conspired to find the hitman.

What happened at the Thorpe trial?

The choice of trial judge came as a surprise. The Honourable Sir Joseph Donaldson Cantley, as Preston explains, "was so little known outside legal circles that not a single news agency possessed a photograph of him. Hesitant of manner, fond of laughing at his own jokes and looking like a startled dormouse in his ermine robes, Cantley was not considered to be an intellectual heavyweight. He was also reckoned to be a crashing snob." Cantley was a gift to Thorpe.

Thorpe also benefitted from a talented lawyer, George Carman. In court he painted Bessell and Scott and Newton as hypocritical, untrustworthy and amoral liars – but his master stroke was to ban Thorpe from entering the witness box. This was a gamble: calling "no evidence" for Thorpe could make him look like he had something to hide. But it also saved him from facing questions from the prosecution that he may have found difficult to answer. It was a gamble that paid off.

And when it came to summing up, Cantley's extraordinary speech became so notorious that it inspired a Peter Cook sketch, Entirely A Matter For You.

"It is right for you to pause and consider whether it is likely that such persons would do the things these persons are said to have done," he told the jury. While the accused were of "hitherto unblemished reputation," Bessell was a "humbug" and Newton a "chump". As for Scott, he was "a hysterical, warped personality, accomplished sponger and very skilful at exciting and exploiting sympathy... he is a crook. He is a fraud. He is a sponger. He is a whiner. He is a parasite."

Unbelievably, he added: "But of course he could still be telling the truth... you must not think that because I am not concealing my opinion of Mr Scott I am suggesting that you should not believe him. That is not for me. I am not expressing any opinion."

Having not expressed any opinion whatsoever, and having warned the jury that they must be beyond all doubt that the witnesses were telling the truth, he called the case to a close.

The jury acquitted all four men on all charges.

What happened to Jeremy Thorpe after the trial?

Thorpe's public reputation had been damaged irreparably. Preston writes: "Although he had been acquitted, Thorpe soon discovered that almost everyone thought he was guilty – and treated him accordingly."

He had already lost his seat in the May 1979 General Election before the trial began, and the fact that he turned down the chance to speak in court and give his own side of the story left many things unexplained. He was never able to return to public life: when he was chosen as Director of Amnesty International's British arm in 1982, there was such a public outcry that the job offer was retracted. His long-running campaign to secure himself a peerage also came to nothing.

Are Jeremy Thorpe and Norman Scott still alive?

In the mid 1980s Thorpe was diagnosed with Parkinson's Disease, which progressively robbed him of his power to communicate. He died in 2014 at the age of 85, outliving his ever-faithful wife Marion by just a few months.

And what of Norman Scott, formerly Norman Josiffe? Now 78, he lives in an ancient farmhouse on Dartmoor in Devon alongside a collection of chickens, horses, and dogs, and has spent the last 20 years in a relationship with an artist. "I’ve got the most lovely life and have had for years," he recently told The Times. But does he think justice has been done? “Not at all.”

He told the newspaper: "I think he should have gone to prison. And that also would have made my life so different, because people would have believed me.”

Few of the other players in the story are still around. Peter Bessell had already been suffering from incurable emphysema at the time of the trial; he died in 1985, having lived his final days in Oceanside, California.

David Holmes was arrested in 1981 for "importuning for an immoral purpose" – that is, approaching men for sex – and exposed in the tabloids. His reputation also suffered because of the Thorpe case, and so he quit the financial and political world and instead became a manager of a roller-disco in Camden.

How accurate is A Very English Scandal?

The BBC drama has been adapted by Russell T Davies from the "non-fiction novel" A Very English Scandal by John Preston, which was published in 2016, with additional research by the production team. But Davies also left space for his imagination.

- For the latest news and expert tips on getting the best deals this year, take a look at our Black Friday 2021 and Cyber Monday 2021

"We did kind of re-research everything," Davies says. "The book had done an awful lot of research and had been published without John Preston being sued. At the BBC you have to re-prove everything, and go through that, and have two sources of evidence for everything.

"Also, at the same time, that's all very well, it's not a documentary – they get me in, I've got a good career as a writer, I have to say, ‘What am I being brought in for?’ And that's to imagine what those people said. And why they said it.

"That's an act of imagination, there's no proof in that, and that's what I'm actually good at. That's what I write about in my career, the madness of men."

This article was originally published on 3 June 2018

The Thorpe affair of the 1970s was a British political and sex scandal that ended the career of Jeremy Thorpe, the leader of the Liberal Party and Member of Parliament (MP) for North Devon. The scandal arose from allegations by Norman Josiffe (otherwise known as Norman Scott) that he and Thorpe had a homosexual relationship in the early 1960s, and that Thorpe had begun a badly planned conspiracy to murder Josiffe, who was threatening to expose their affair.

Thorpe on the trial

All three [principal prosecution witnesses] had ... been destroyed in cross-examination, and the prosecution's case at its close was shot through with lies, inaccuracies and admissions to such an extent that the defence decided not to give evidence. To have done so would have prolonged the trial unnecessarily.

Jeremy Thorpe, In My Own Time[14

Bessell's evidence against Thorpe, reported in the Daily Mirror during the pre-trial committal proceedings, November 1978

Obituary: Jeremy Thorpe - BBC News

https://www.bbc.com/news/uk-

James Landale looks back at the life of Jeremy Thorpe

Jeremy Thorpe, who has died aged 85 after a long battle with Parkinson's Disease, led the Liberal Party with flair and flamboyance.

His energetic campaigning and powerful oratory attracted many voters and he came close to achieving a share of government for his party.

Under his leadership, the Liberals looked to be regaining their position as a strong force in British politics.

But his political career ended when his life was engulfed in scandal and he faced trial on charges of conspiracy and incitement to murder.

John Jeremy Thorpe was born in Surrey on 29 April 1929.

He came from a Conservative family - both his father and grandfather were Tory MPs. One of his ancestors was parliamentary Speaker Thomas Thorpe, who was beheaded by a mob in 1461.

Election success

He was sent to a school in Connecticut in 1940 to escape the Blitz.

One historian has suggested that the liberal regime at his American school played a large part in formulating his political thinking and was, no doubt, a huge contrast to Eton where he went from 1943.

He read law at Trinity College, Oxford where he cut a dash, both by wearing Edwardian-style clothes and as a noted debater. He became chairman of the Liberal Club and then the Oxford Union.

Image caption,

Acknowledging his supporters in the 1974 election

While training as a barrister he set out to find a parliamentary seat and was selected for Conservative-held North Devon, firmly in the west country Liberal heartland.

His energetic campaigning, and inspiring performances as an orator saw him halve the Conservative majority in the 1955 general election.

Just four years later, he won the seat by the narrowest of margins, a rare Liberal triumph in what had been a poor election showing for the party elsewhere in the country.

Conference favourite

He entered the 1960s as a pioneering campaigner for human rights, attacking South Africa's policy of apartheid and the post-colonial excesses in South East Asia.

He also achieved a reputation as something of a wit exemplified by his observation on Harold Macmillan's dismissal of a third of the Conservative cabinet in 1962.

"Greater love hath no man than this," quipped Thorpe, "that he lay down his friends for his life".

He became a favourite at Liberal party conferences and served as the party's treasurer before being elected leader in 1967 promising to turn the Liberals into a radical pioneering force.

Norman Scott claimed a sexual relationship with Thorpe

Norman Scott claimed a sexual relationship with Thorpe

However Edward Heath's win in the 1970 general election dashed hopes of a Liberal revival and shortly after it Thorpe's young wife Caroline was killed in a car crash.

Three years later he married Marion Stein, a noted concert pianist and the divorced wife of the Queen's first cousin, the Earl of Harewood.

Helped by Thorpe's elegant appearance and charismatic style, the Liberals won 14 seats in the February 1974 election.

With a hung parliament, Conservative leader, Edward Heath, approached Thorpe to discuss a possible coalition.

Thorpe was attracted by the offer of a seat in Cabinet, but met opposition from his own MPs.

Denial

In the event, Harold Wilson's clear victory in the October 1974 election ended any hopes that the Liberals might have a share of power.

Within two years, stories were circulating about Thorpe's relationship with a former male model, Norman Scott.

It was made worse because the relationship was alleged to have started in 1961, when male homosexual acts were illegal.

The story broke when Scott was appearing at a court in Barnstaple on a minor social security charge.

During the hearing, Scott shouted out, "I am being hounded because of my sexual relationship with Jeremy Thorpe." He gave a statement to the police but no action was taken.

Trial

Thorpe issued an immediate denial but when an affectionate letter between them appeared in the press, Thorpe resigned as leader.

But worse was to come. Eighteen months later, a man called Andrew Newton was released from prison.

He had been jailed on charges arising from an incident on Exmoor in which Norman Scott's dog, Rinka, was shot.

He claimed that he had been paid by a leading Liberal supporter to kill Scott because of his blackmail threats but said he had lost his nerve and shot the dog instead.

Arriving at the Old Bailey in 1979 with wife Marion

Nine more months of police investigation led to Thorpe and three associates being charged with conspiring to murder Scott.

The 1979 trial was postponed for eight days at Thorpe's request so that he could contest his North Devon seat in the May general election. He was heavily defeated.

The trial attracted reporters from all over the world. It took 20 days for the prosecution to present its case to the jury while defence evidence occupied just a single day.

Trial

Thorpe issued an immediate denial but when an affectionate letter between them appeared in the press, Thorpe resigned as leader.

But worse was to come. Eighteen months later, a man called Andrew Newton was released from prison.

He had been jailed on charges arising from an incident on Exmoor in which Norman Scott's dog, Rinka, was shot.

He claimed that he had been paid by a leading Liberal supporter to kill Scott because of his blackmail threats but said he had lost his nerve and shot the dog instead.

Arriving at the Old Bailey in 1979 with wife Marion

Arriving at the Old Bailey in 1979 with wife Marion

Nine more months of police investigation led to Thorpe and three associates being charged with conspiring to murder Scott.

The 1979 trial was postponed for eight days at Thorpe's request so that he could contest his North Devon seat in the May general election. He was heavily defeated.

The trial attracted reporters from all over the world. It took 20 days for the prosecution to present its case to the jury while defence evidence occupied just a single day.

Amnesty International

On the advice of his barrister, George Carman QC, Thorpe and his co-defendants elected not to go into the witness box.

Eventually, after six weeks, the charges were dismissed. For two years Jeremy Thorpe stayed out of the public eye.

But the affair resurfaced again when one of his co-defendants, David Holmes, a former deputy treasurer of the Liberal Party, wrote a series of articles for the News of the World newspaper.

In the first of them he claimed that Thorpe did incite him to murder Norman Scott. Thorpe's solicitor immediately issued a rebuttal and the director of public prosecutions said there was no question of another trial.

At a book signing in 1999

But Thorpe's public life was finished.

Shortly after his acquittal he was offered the post of director general of the British section of Amnesty International.

He had previously been a valuable source of information to the organisation, particularly on the subject of human rights abuses in Ghana.

But there was huge opposition from Amnesty's members and the appointment was never made.

His later years saw the onset of Parkinson's Disease. But he kept in close touch with the Westminster he loved, despite painful memories.

He became the President of the North Devon Liberal Association, later Liberal Democrat Association, and received a standing ovation when he appeared at the 1997 Liberal Democrat conference.

In an interview in 2009 the ailing former politician reflected on the events that had brought him down

"If it happened now," he said, " I think the public would be kinder."

Norman Josiffe

Norman Josiffe (born 12 February 1940), better known in the media as Norman Scott, is an English former dressage trainer[citation needed] and model who was a key figure in the Thorpe affair, a major British political scandal of the 1970s. The scandal revolved around the alleged plot by his ex-boyfriend, Liberal Party leader Jeremy Thorpe, to murder Scott after Scott threatened to reveal their sexual relationship to the media.

Early life, 1940–1960

Josiffe was born in Sidcup, Kent,[1] to Ena Dorothy Josiffe (née Lynch,[2] formerly Merritt,[3] 1907–1985), and Albert Norman Josiffe (1908–1983),[2][4] her second husband, who abandoned his wife and child soon after Norman's birth.[5] Educated at Bexleyheath, he later changed his surname to "Lianche-Josiffe" by amending his mother's maiden name, Lynch, and for a time called himself "the Hon Norman Lianche-Josiffe".[6][7]

Relationship with Jeremy Thorpe, murder attempt and trial, 1961–1979

In 1961, Josiffe was working as a groom for Brecht Van de Vater (born Norman Vivian Vater),[8] at Kingham Stables in Chipping Norton, Oxfordshire, when he met Jeremy Thorpe, MP, a friend of Vater. After Josiffe left his job at Vater's stables, he suffered from mental illness and spent some time in a psychiatric hospital. On 8 November 1961, a week after discharging himself from the Ashurst clinic in Oxford, he went to the House of Commons in London to see Thorpe. He was penniless, homeless and, worse, had left Vater's employment without his National Insurance card which, he believed he needed to obtain regular work and access to social and unemployment benefits. Thorpe promised he would help.[9] This was when the relationship between the two men was alleged to have started. Thorpe gave him the nickname "Bunnies"[10] but always denied any physical element in the relationship. When Thorpe took him to stay with his mother, Ursula Thorpe, Josiffe introduced himself as "Peter Johnson".[6] Josiffe's claims of mistreatment by Thorpe led to Josiffe being reported to the police, in the course of which the relationship was revealed.[11]

The relationship allegedly led indirectly to the 1975 attempted murder of Josiffe, who was by then calling himself Norman Scott.[12] His attacker, Andrew Newton, was arrested[13] after shooting dead Josiffe's dog, Rinka, but it was not until later that Josiffe's accusations against Thorpe became public.

Although the Sexual Offences Act 1967 had decriminalised homosexual acts in most of the UK, the resulting scandal lost Thorpe his popular support and he was forced to stand down as leader of the Liberal Party. In 1979, Scott testified at Thorpe's trial, whereat Thorpe and three others were acquitted of conspiracy to murder.

Personal life

On 13 May 1969,[14] after his relationship with Thorpe, Josiffe (now calling himself Scott) married Angela Mary Susan Myers (1945–1986), sister-in-law of the English comedy actor Terry-Thomas. Susan Scott was already two months pregnant at the time of their marriage and her family were not supportive of the marriage – her mother and sister refused to attend the ceremony and Captain Myers (Josiffe's new father-in-law) denounced Scott as homosexual at the wedding reception stating that the marriage "was doomed". The couple had a son – Diggory Benjamin W. Scott [15], who was born, later in 1969, in Spilsby, Lincolnshire.[11][16] Susan Scott left Scott in 1970, subsequently divorced, remarried in 1975 and died in 1986.

In 1971, while living in Tal-y-Bont in North Wales, where he found casual work, Scott met widow Gwen Parry-Jones, whose late husband had been a soldier in the Welsh Guards. She was a former local village postmistress and was an acquaintance of Liberal MP Emlyn Hooson. Parry-Jones arranged a meeting with Hooson, who interviewed Scott (with Liberal MP David Steel) about his relationship with Thorpe and started his own investigations, but could not substantiate the allegations. After the break-up with Scott, Parry-Jones became very depressed. In 1972, her aunt failed to get any response at her home for several weeks and the police discovered that she had died, which the coroner subsequently recorded as alcohol poisoning.[16]

In 1975, he began a relationship with a woman named Hilary Arthur, with whom, in May 1976, he had a daughter, Bryony.[17][18]

After 1979, Scott retreated into obscurity. At the time of Thorpe's death in 2014, he was living in Ireland,[12] but by the time of the 2018 dramatisation of his relationship with Thorpe, he had returned to the UK and was living again in Devon.[19]

In popular culture

In 2016, A Very English Scandal, by John Preston about the Thorpe scandal and subsequent trial was published.[20]

In 2018, a BBC miniseries also called A Very English Scandal was aired in which Scott was portrayed by Ben Whishaw.[21] Scott remarked to The Irish News: "I'm portrayed as this poor, mincing, little gay person ... I also come across as a weakling and I've never been a weakling."[22]

The mini-series' director, Stephen Frears, has described Scott as "erratic", stating that his reactions to both book and television series are inconsistent.[23] Andrew Rawnsley, reviewing Thorpe's biography by Michael Bloch, described both Thorpe and Josiffe as "liars" and "fantasists".[24]

References

Citation

- ^ General Register Office; United Kingdom; Birth Register Indexes; Reference: Volume 2a, p. 2064

- ^ Jump up to:a b General Register Office. England and Wales Civil Registration Indexes. London: General Register Office. Bromley, Q4

- ^ General Register Office. England and Wales Civil Registration Indexes. London: General Register Office. Dartford, Q2

- ^ General Register Office. England and Wales Civil Registration Indexes. London: General Register Office. Bromley, Q2

- ^ Simon Freeman with Barrie Penrose: Rinkagate: The Rise and Fall of Jeremy Thorpe. Bloomsbury, 1996. p. 37.

- ^ Jump up to:a b "Murder most Liberal". The Telegraph. 19 October 1996. Archived from the original on 18 December 2009. Retrieved 28 May 2018.

- ^ Leonard Downie, Jr. (3 June 1979). "Murder Conspiracy Trial Leaves Thorpe a Ruined Man". Washington Post. Retrieved 28 May 2018.

- ^ "Murder most Liberal". telegraph.co.uk. 18 October 1996. Archived from the original on 18 December 2009. Retrieved 9 July 2018.

- ^ Freeman and Penrose, pp. 40–43

- ^ "Who was Norman Scott and what was his relationship with Jeremy Thorpe?". Radio Times. Retrieved 28 May 2018.

- ^ Jump up to:a b Ash Percival (20 May 2018). "'A Very English Scandal': The Real Story Of Jeremy Thorpe, Norman Scott And The Alleged Murder Plot That Rocked British Politics". HuffPost. Retrieved 28 May 2018.

- ^ Jump up to:a b Gordon Rayner (4 December 2014). "Jeremy Thorpe scandal: where are they now?". The Telegraph. Retrieved 28 May 2018.

- ^ Preston, John (2016). A Very English Scandal. London: Viking. pp. 207–208. ISBN 978-0241215722.

- ^ General Register Office. England and Wales Civil Registration Indexes. London, England: General Register Office. Kensington, Q2

- ^ https://archive.spectator.co.uk/article/16th-december-1978/6/another-voice

- ^ Jump up to:a b "Did Norman Scott really get married and have a baby?". Radio Times. Retrieved 28 May 2018.

- ^ https://archive.spectator.co.uk/article/16th-december-1978/6/another-voice

- ^ Preston, John (5 May 2016). "Chapter 28". A Very English Scandal: Now a Major BBC Series Starring Hugh Grant. Penguin Books Limited. p. 518. ISBN 978-0-241-97375-2.

- ^ Helen Rumbelow (12 April 2018). "Jeremy Thorpe tried to kill me – Norman Scott on the scandal that shook Seventies Britain". The Times. Retrieved 3 June 2018.

- ^ Chris Mullin (9 May 2016). "A Very English Scandal review – Jeremy Thorpe's fall continues to fascinate". The Guardian. Retrieved 31 December 2019.

- ^ Emma Nolan (21 May 2018). "A Very English Scandal: Who was Norman Scott? Who was his wife?". The Express. Retrieved 28 May 2018.

- ^ "Norman Scott criticises 'weakling' portrayal in BBC's A Very English Scandal". The Irish News. 6 May 2018. Retrieved 28 May 2018.

- ^ Mark Brown (3 June 2018). "Stephen Frears queries reopening of Jeremy Thorpe investigation". The Guardian. Retrieved 31 December 2019.

- ^ Andrew Rawnsley (18 January 2015). "Jeremy Thorpe review – Michael Bloch's gripping and insightful biography". The Guardian. Retrieved 28 May 2018.

Sources

- Freeman, Simon; Penrose, Barrie (1997). Rinkagate: The Rise and Fall of Jeremy Thorpe. London: Bloomsbury Publications. ISBN 978-0-7475-3339-9.

Thorpe, while admitting that the two had been friends, denied any such relationship. With the help of political colleagues and a compliant press, he was able to ensure that rumours of misconduct went unreported for more than a decade. Scott's allegations were a persistent threat, however, and by the mid-1970s he was regarded as a danger both to Thorpe and to the Liberal Party, which was then enjoying a resurgence of popularity and was close to a place in government. Attempts to buy or frighten Scott into silence were unsuccessful, and the problem deepened, until the fallout following the shooting of his dog during a possible murder attempt by a hired gunman in October 1975 brought the matter into the open. After further newspaper revelations, Thorpe was forced to resign the Liberal leadership in May 1976, and subsequent police investigations led to him being charged, along with three others, with conspiracy to murder Scott. Before the case came to trial, Thorpe lost his parliamentary seat at the 1979 general election.

At the trial in May 1979, the prosecution's case depended heavily on the evidence of Scott, Thorpe's former parliamentary colleague Peter Bessell, and the hired gunman, Andrew Newton. None of these witnesses impressed the court. Bessell's credibility was undermined by the revelations of his financial arrangements with The Sunday Telegraph. In his summing-up the judge was scathing about the prosecution's evidence, and all four defendants were acquitted. Nevertheless, Thorpe's public reputation was damaged irreparably by the case. He had chosen not to testify at the trial, which left several matters unexplained amid public disquiet.

Thorpe's retirement into private life was followed by the onset of Parkinson's disease in the mid-1980s, and he made few public statements afterwards. He eventually achieved a reconciliation with the North Devon Liberal Democrat constituency party, of which he was honorary president from 1988 until his death in 2014. Allegations of suppression of evidence by the police before the trial were under investigation from 2015, culminating in June 2018 when the police said that there was no new evidence and the case would remain closed.

Background

Homosexuality and English law

editBefore the passage of the Sexual Offences Act 1967, which decriminalised most homosexual acts in England and Wales (but did not apply to Scotland or Northern Ireland), all sexual activity between men was illegal throughout the United Kingdom, and carried heavy criminal penalties. Antony Grey, a secretary of the Homosexual Law Reform Society, wrote of "a hideous aura of criminality and degeneracy and abnormality surrounding the matter".[1]

Political figures were particularly vulnerable to exposure; William Field, the Labour MP for Paddington North, was forced to resign his seat in 1953 after a conviction for soliciting in a public lavatory.[2] In the following year Lord Montagu of Beaulieu, the youngest peer in the House of Lords, was imprisoned for a year after being convicted of "gross indecency", victim of a virulent "drive against male vice" led by the Home Secretary, Sir David Maxwell Fyfe.[3]

Four years later public attitudes had changed little. When Ian Harvey, a junior Foreign Office minister in Harold Macmillan's government, was found guilty of indecent behaviour with a Coldstream Guardsman in November 1958, he lost both his ministerial job and his parliamentary seat at Harrow East. He was ostracised by the Conservative Party and by most of his former friends, and never again held a position in public life.[4] Thus, anyone entering politics at that time knew that revelations of homosexual activity would likely bring such a career to a swift end.[5]

Barnstaple, the main town in Thorpe's North Devon constituency

Thorpe

John Jeremy Thorpe was born in 1929, the son and grandson of Conservative MPs. He attended Eton, then studied law at Trinity College, Oxford, where, having decided on a political career, he devoted his main energies to making a personal impact rather than to his studies.[6] Rejecting his Conservative background, he joined the small, centrist Liberal Party—which by the late 1940s was a declining force in British politics, but still offered a national platform and a challenge to an ambitious young politician.[7] He became secretary and eventually President of the Oxford Liberal Club, and met many of the party's leading figures. In the Hilary term (January–March) of 1950–51 Thorpe served as President of the Oxford Union.[8]

John Jeremy Thorpe was born in 1929, the son and grandson of Conservative MPs. He attended Eton, then studied law at Trinity College, Oxford, where, having decided on a political career, he devoted his main energies to making a personal impact rather than to his studies.[6] Rejecting his Conservative background, he joined the small, centrist Liberal Party—which by the late 1940s was a declining force in British politics, but still offered a national platform and a challenge to an ambitious young politician.[7] He became secretary and eventually President of the Oxford Liberal Club, and met many of the party's leading figures. In the Hilary term (January–March) of 1950–51 Thorpe served as President of the Oxford Union.[8]

In 1952, while studying at the Inner Temple prior to his call to the bar, Thorpe was adopted as prospective Liberal parliamentary candidate for the North Devon constituency, a Conservative-held seat where, at the 1951 general election, the Liberals had finished in third place behind Labour.[9] Thorpe worked in the constituency tirelessly, using the slogan "A Vote for the Liberals is a Vote for Freedom", and at the 1955 general election, had halved the sitting Conservative MP James Lindsay's majority.[8] Four years later, in October 1959, he captured the seat with a majority of 362, one of six successful Liberals in what was generally an electoral triumph for the Conservative Macmillan government.[10][11]

The writer and former MP Matthew Parris described Thorpe as one of the more dashing among the new MPs elected in 1959.[12] Thorpe's chief political interest lay in the field of human rights, and his speeches criticising apartheid in South Africa attracted the attention of the South African Bureau of State Security (BOSS), who took note of this rising star in the Liberal Party.[8][13] Thorpe was briefly considered as best man at the 1960 wedding of his Eton contemporary Antony Armstrong-Jones to Princess Margaret, but was rejected when vetting checks indicated that he might have homosexual tendencies.[14][15][16] The security agency MI5, which routinely keeps records on all Members of Parliament, added this information to Thorpe's file.[5][17]

Josiffe, later named Scott

editNorman Josiffe was born in Sidcup, Kent, on 12 February 1940[18]—he did not assume the name Scott until 1967. His mother was Ena Josiffe, née Lynch; Albert Josiffe, her second husband, abandoned the family home soon after Norman's birth. Norman's early childhood was relatively happy and stable. After leaving school at 15 with no qualifications, he acquired a pony by means of an animal charity, and became a competent rider.[19][20] When he was 16 he was prosecuted for the theft of a saddle and some pony feed, and was put on probation. With the encouragement of his probation officer he took lessons at Westerham Riding School at Oxted in Surrey, and eventually found work at a stable in Altrincham in Cheshire. After moving there he chose to cut all links with his family, and began to call himself "Lianche-Josiffe" ("Lianche" being a stylised version of "Lynch"). He also hinted at an aristocratic background, and of family tragedies that had left him orphaned and alone.[21]

In 1959 Josiffe moved to the Kingham Stables in Chipping Norton, Oxfordshire, where he learned dressage while working as a groom. The stables were owned by Norman Vater, the self-made son of a coalminer who, like Josiffe, had inflated his name and was known as "Brecht Van de Vater". In the course of his rise, Vater had made numerous friends in higher social circles, among them Thorpe. Initially, Josiffe was settled and happy at the stables, but his relationship with Vater deteriorated in the face of the latter's assertive and demanding manner, and he was unable to form good relationships with his fellow-workers.[22] He began to evidence the kind of behaviour which a journalist would later summarise as his "extraordinary talent for wheedling his way into people's sympathy before turning their lives to misery with his hysterical temper-tantrums."[23]

Bessell

editPeter Bessell, eight years older than Thorpe, had a successful business career before entering Liberal politics in the 1950s.[24] He came to the party leadership's attention in 1955 when, as the Liberal candidate in the Torquay by-election, he substantially increased his party's vote in the first of a series of impressive Liberal results during the 1955–59 parliament.[25] He was subsequently selected as candidate for the more winnable constituency of Bodmin, and became both an admirer and personal friend of Thorpe, who in turn was impressed by Bessell's apparent business acumen.[26] At Bodmin in the 1959 general election, Bessell reduced the Conservative majority, and he followed this in the October 1964 election with victory by over 3,000 votes.[24] With the prestige of the letters "MP" after his name, Bessell set out in pursuit of serious money-making, while staying close to Thorpe whom he considered the likely next leader of the Liberal Party.[27]

Bessell noted that Thorpe, for all his gregariousness and warmth, appeared to have no female friends and lacked any interest in women. The former Liberal MP Frank Owen confided to Bessell his suspicions that Thorpe was homosexual; other West Country Liberals had formed the same opinion.[28] Aware that exposure as a gay man would end Thorpe's career, Bessell became his self-appointed protector, even to the extent, he later said, of falsely claiming to be bisexual, as a means of acquiring his friend's confidence.[29]

Holmes

editDavid Holmes, one of four assistant treasurers of the Liberal Party appointed by Thorpe in 1965, had been best man at Thorpe's wedding and was completely loyal to him.[30] He was godfather to Thorpe's son Rupert, born in 1969.[31] Holmes took over the role of Thorpe's protector after Bessell moved to the United States in January 1974.[32] When charged in 1978, he was described as David Malcolm Holmes (48), merchant banker, of Eaton Place, Belgravia.[33][34] He died in 1990, leaving a substantial fortune.[35]

Origins

editThorpe–Scott friendship

editIn late 1960 or early 1961, Thorpe visited Vater at the Kingham Stables, and briefly met Josiffe. He was sufficiently taken with the young man to suggest that, should Josiffe ever need help, he should call on him at the House of Commons.[21] Soon after this, Josiffe left the stables after a serious disagreement with Vater. He then suffered a mental breakdown, and for much of 1961 was under psychiatric care. On 8 November 1961, a week after discharging himself from the Ashurst clinic in Oxford, Josiffe went to the House of Commons to see Thorpe. He was penniless, homeless and, worse, had left Vater's employment without the National Insurance card which, at that time, was essential for obtaining regular work and access to social and unemployment benefits. Thorpe promised he would help.[36]

According to Josiffe's account, a homosexual liaison with Thorpe began that same evening, at the home of Thorpe's mother Ursula Thorpe (née Norton-Griffiths, 1903–1992) in Oxted and continued for several years.[37][38] Thorpe, while acknowledging that a friendship developed, denied any sexual dimension in the relationship.[39][n 1] Thorpe organised accommodation for Josiffe in London, and a longer-term stay with a family in Barnstaple, in the North Devon constituency. He paid for advertisements in Country Life magazine, in an effort to find work with horses for his friend,[40] arranged various temporary jobs, and promised to help Josiffe to realise an ambition to study dressage in France. On the basis of Josiffe's claim that his father had died in an air crash, Thorpe's solicitors investigated whether any money was due, but found that Albert Josiffe was alive and well in Orpington.[41]

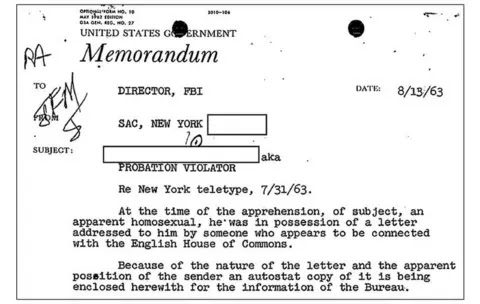

When, early in 1962, the police questioned Josiffe about the alleged theft of a suede jacket, Thorpe persuaded the investigating officer that Josiffe was recovering from mental illness, and was under his care. No further action was taken.[37][42] In April 1962 Josiffe obtained a replacement National Insurance card which, he later said, was retained by Thorpe who had assumed the role of his employer. This was denied by Thorpe, and the "missing card" remained an ongoing source of grievance for Josiffe.[43] He began to feel marginalised by Thorpe, and in December 1962, in a fit of depression, confided to a friend his intention to shoot the MP and commit suicide. The friend alerted the police, to whom Josiffe gave a detailed statement of his sexual relations with Thorpe, and produced letters to support his story.[44] None of this evidence impressed the police sufficiently for them to take action, although a report on the matter was added to Thorpe's MI5 file.[44]

In 1963, a relatively calm period in Josiffe's life as a riding instructor in Northern Ireland ended after he was seriously hurt in an accident at the Dublin Horse Show.[45] He moved back to England, and eventually found a job at a riding school in Wolverhampton, where he stayed for several months before his erratic behaviour proved too much, and he was asked to leave.[46] After a period of aimlessness in London, Josiffe saw an advertisement for a groom's post in Porrentruy in Switzerland. Thorpe used his influence to secure him the job. Josiffe left for Switzerland in December 1964, but returned to England almost immediately with complaints that conditions were impossible. In his hurry to depart he left his suitcase behind, which contained letters and other documents that, he believed, supported his claims to a sexual relationship with Thorpe.[47]

Threats and counter-measures

Thorpe proved to be a lively and witty performer in the cut and thrust of parliamentary debates, and his presence in the House of Commons was soon noticed. In July 1962, in the wake of some disastrous Conservative by-election performances, Macmillan sacked seven cabinet ministers in what was known as the "Night of the Long Knives". Thorpe's comment—"Greater love hath no man than this, that he lay down his friends for his life"—was widely regarded in the press as the most apt verdict on the prime minister.[13] Thorpe raised his political profile with effective attacks on government bureaucracy, and in the October 1964 general election was returned in North Devon with an increased majority.[48] A year later he secured the office of Liberal Party treasurer, a significant step towards his ambition to become the next party leader.[49]

By early 1965 Josiffe was in Dublin, where he worked at various horse-related jobs while continuing to harass Thorpe by letter about his missing luggage and the continuing National Insurance card issue.[50] Thorpe rejected any responsibility for these matters.[51] In mid-March 1965 Josiffe wrote a long letter to Thorpe's mother, which began: "For the last five years, as you probably know, Jeremy and I have had a homosexual relationship." The letter blamed Thorpe for awakening "this vice that lies latent in every man", and accused him of callousness and disloyalty.[52] Ursula Thorpe gave the letter to her son, who drafted a quasi-legal statement rejecting the "damaging and groundless accusations" and accusing Josiffe of attempting to blackmail him. The document was never sent; instead, Thorpe turned to Bessell for advice.[53]

Bessell, anxious to be of service to his party's highest-profile figure, flew to Dublin in April 1965. He found that Josiffe was being advised by a sympathetic Jesuit priest, Father Sweetman,[54] who believed that at least some of Josiffe's allegations might be true; otherwise, he asked Bessell, why had he flown all the way from London to deal with them?[55] Bessell warned Josiffe of the consequences of attempting to blackmail a public figure, but in a more conciliatory vein promised to help recover the missing luggage and insurance card. He also hinted at the possibility of an equestrian job in America.[54] Bessell's intervention appeared to contain the problem, particularly as Josiffe's suitcase was recovered shortly afterwards—although letters implicating Thorpe had been removed.[56] For most of the following two years Josiffe remained largely quiescent in Ireland, attempting to establish himself in various careers; part of this time was spent in a monastery. It was during this period that he formally adopted the name of Scott.[57][n 2]

In April 1967 Scott wrote to Bessell from Ireland, asking for help in obtaining a passport in his changed name so that he could begin a new life in America.[57] A second, less positive letter, dated July, indicated that Scott had returned to England and was once again in difficulties, with medical bills and other debts. His lack of an insurance card prevented him from claiming benefits.[59] By this time, Thorpe had succeeded Jo Grimond as leader of the Liberal Party.[60][n 3] To resolve Scott's immediate problems, and to prevent a resumption of his tirades against the new party leader, Bessell began paying him a "retainer" of between £5 and £10 a week, ostensibly in lieu of lost national insurance benefits.[61] Bessell also arranged Scott's new passport, but by this time Scott had abandoned his American plans and wished to establish a career as a model. He asked Bessell for £200 to set him up; Bessell refused, but in May 1968 gave him £75, on the understanding there would be no further demands for a year.[62]

Developments

editIncitement

editThorpe's leadership of the Liberals was not, initially, an unqualified success; his local campaigning skills did not readily transfer to set speeches on national or international issues, and some sections of the party became restless.[63] His engagement to Caroline Allpass, announced in April 1968, reassured those in the party who had reservations about his private life; others were shocked by Thorpe's emphasis on the political motivation for the marriage—worth five points in the polls, he opined to Mike Steele, the party's press officer.[64] For much of 1968 Thorpe was untroubled by Scott, who had acquired new friends and, according to Bessell, had burned his Thorpe letters.[65] His reappearance in November 1968, again penniless and without prospect of work, was particularly unwelcome to Thorpe, as he fought to establish his leadership credentials. Bessell provided immediate relief by resuming the weekly cash retainer, but this was a short-term respite.[30]

Early in December 1968 Bessell was summoned to Thorpe's office in the House of Commons. According to Bessell, Thorpe said of Scott: "We've got to get rid of him", and later: "It is no worse than shooting a sick dog."[66] Bessell said later that he was unsure whether Thorpe was serious, but decided to play along, by discussing various ways of getting rid of Scott's body. Thorpe supposedly thought that disposal down one of Cornwall's many disused tin mines offered the best option, and also suggested his friend David Holmes as an appropriate assassin.[30]

Bessell further maintained that in January 1969 Thorpe called him to a meeting together with Holmes, and that again Thorpe put forward suggestions for eliminating Scott. These were dismissed as impractical or ridiculous by Bessell and Holmes, who nevertheless agreed to give the matter further consideration. They hoped, said Bessell, that if they stalled, Thorpe would see the absurdity of his murder scheme and abandon it. Holmes, who largely confirmed Bessell's account of the meeting, later justified this decision on the grounds that "if we had simply said no, he might have gone elsewhere—and that might have led to an even greater disaster."[30] According to Bessell and Holmes, discussions of the plan ended in May 1969, after the surprising news of Scott's wedding that month.[66]

Party enquiry

By early 1971, Thorpe's political career had stalled. He had led the party to a disastrous performance in the general election of June 1970; in an unexpected victory for the Conservatives under Edward Heath, the Liberals lost seven of their thirteen parliamentary seats, and Thorpe's majority in North Devon fell to below 400.[67] Bessell, with mounting business worries, did not stand for re-election in Bodmin.[24] Thorpe faced censure for his conduct of a campaign during which he had spent extravagantly and left the party on the verge of bankruptcy; but the matter was put aside in a wave of sympathy when his wife Caroline was killed in a road accident 11 days after the election. Thorpe was devastated; he continued as leader, but for the next year performed little beyond routine party duties.[67]

The village of Tal-y-bont, North Wales, where Scott lived in 1971

Meanwhile, Bessell's efforts ensured that for the time being the Scott threat was kept at bay. The missing insurance card meant that Scott's wife, who was pregnant, could not claim maternity benefits. Scott threatened to talk to newspapers, but the matter was resolved by the issue of an emergency card after Bessell's intervention at the Department of Health and Social Security.[68] In 1970 Scott's marriage collapsed; he blamed Thorpe, and again threatened exposure.[69] Bessell successfully prevented Thorpe's name being mentioned in court during the divorce proceedings, and arranged that Thorpe would anonymously pay the legal costs.[70][71] Early in 1971 Scott moved to a cottage in the village of Tal-y-bont in North Wales, where he befriended a widow, Gwen Parry-Jones. He sufficiently persuaded her of his mistreatment at the hands of Thorpe that she contacted the Liberal MP for the adjoining constituency of Montgomeryshire—Emlyn Hooson, on the right wing of the party and a friend of neither Thorpe nor Bessell. Hooson suggested a meeting at the House of Commons.[72]

On 26 and 27 May 1971 Scott told his story to Hooson and David Steel, the Liberals' chief whip. Neither was fully convinced, but felt the matter warranted further investigation. Against Thorpe's wishes, a confidential party enquiry was arranged for 9 June, to be chaired by Lord Byers, the leader of the Liberals in the House of Lords. At the enquiry Byers took a tough line against Scott, failing to offer him a chair and treating him, Scott said, "like a boy at school up before the headmaster."[73] Byers's unsympathetic manner quickly unsettled Scott, who changed the details of his story several times and frequently broke down in tears. Byers suggested that Scott was a common blackmailer who needed psychiatric help. Declaring that Byers was a "pontificating old sod", Scott fled the room.[66] The enquiry then questioned police officers about letters which Scott had shown to the police in 1962, but were told that these were inconclusive.[74] Thorpe persuaded the Home Secretary, Reginald Maudling, and the Metropolitan Police Commissioner, John Waldron, to inform Byers that there was no police interest in Thorpe's activities, and no evidence of wrongdoing on his part.[75] As a result, the enquiry dismissed Scott's allegations.[66]

Further threats

Angry at his treatment by the Byers inquiry, Scott sought other means of pursuing his vendetta against Thorpe. In June 1971 he met Gordon Winter, a South African journalist who was also an agent for the South African intelligence agency BOSS. Scott provided details of his supposed seduction by Thorpe, a story which Winter assured his BOSS masters would destroy Thorpe and the Liberal Party. He found that no newspaper would print the story on largely uncorroborated and unreliable evidence.[76] In March 1972 Scott's friend Gwen Parry-Jones died; Scott used the inquest to denounce Thorpe for ruining his life and driving Parry-Jones to her death. None of these accusations were published.[77] Depressed, Scott retreated into a state of torpor, assisted by tranquillisers, and for a while presented no threat to Thorpe.[78]

In 1972 and 1973 Thorpe's political fortunes, and those of the Liberals, revived. Thorpe's personal standing was enhanced when, on 14 March 1973, he married Marion, Countess of Harewood, whose former husband was a first cousin to the Queen.[80] After a series of by-election victories and local government gains, an electoral breakthrough for the party looked plausible when Heath called a general election in February 1974. In that election, with more than six million votes (19.3% of those cast), the Liberals achieved by far their best election result since the Second World War,[81] but under the first-past-the-post voting system this large vote translated into only 14 seats. As neither major party won an overall majority, these seats gave Thorpe (whose personal majority in North Devon increased to 11,072)[82] significant leverage.[83] He was briefly in coalition discussions with Heath, who was prepared to give cabinet posts to Thorpe and other senior Liberals. Thorpe later denied that there was any serious prospect of agreement,[84] and in March 1974 Harold Wilson formed a minority Labour government. In the second 1974 general election, in October, Wilson achieved a narrow majority; the Liberals lost ground, with 5.3 million votes and 13 MPs.[83][n 4]

After Parry-Jones's death Scott lived quietly for a while in the West Country.[86] In January 1974 he met Tim Keigwin, Thorpe's Conservative opponent in North Devon, and gave his version of his relationship with Thorpe. Keigwin was advised by the Conservative leadership that the material should not be used.[87] Scott also confided in his doctor, Ronald Gleadle, who was treating him for depression. He had shown Gleadle his dossier of documents; the doctor, without Scott's knowledge or consent, sold the papers to Holmes, who had assumed the role of Thorpe's protector after Bessell settled permanently in California in January 1974. Holmes paid £2,500 for the documents, which were promptly burned in the home of Thorpe's solicitor.[32] A further cache of papers was discovered in November 1974, by builders renovating a London office formerly used by Bessell. They found a briefcase containing letters and photographs that apparently compromised Thorpe, among them Scott's 1965 letter to Ursula Thorpe. Undecided what to do with their find, they took it to the Sunday Mirror newspaper. Sidney Jacobson, the paper's deputy chairman, decided not to publish the material and passed the briefcase and its content to Thorpe.[80] Copies of the documents were kept in the newspaper's files.[88]

Alleged conspiracy

In their analysis of the case, the journalists Simon Freeman and Barry Penrose state that Thorpe probably formed the outline of a plan to silence Scott early in 1974, after the latter's re-emergence became a matter of increasing concern.[89] Holmes later said that Thorpe was insistent that Scott be killed: "[Jeremy felt] he would never be safe with that man around".[90] Uncertain how to proceed, late in 1974 Holmes approached a business acquaintance, a carpet salesman named John Le Mesurier (not to be confused with the actor of that name). Le Mesurier introduced Holmes to George Deakin, a fruit machine salesman who, he thought, would have contacts with people who might be prepared to deal with Scott. Holmes and Le Mesurier concocted a story involving a blackmailer who needed to be frightened off; Deakin agreed to help.[91] In February 1975 Deakin met Andrew Newton, an airline pilot, who said he was willing to deal with Scott for an appropriate fee—between £5,000 and £10,000 was suggested.[92] Deakin put Newton in touch with Holmes. Newton always said that he had been hired to kill, not frighten, citing the size of the fee that he was offered—too much, he said, simply to scare someone.[93]

While these arrangements proceeded, Thorpe wrote to Sir Jack Hayward, the Bahamas-based millionaire businessman, who had given generously to the Liberal Party in the past. In the wake of the Liberals' February 1974 election successes, Thorpe asked for £50,000 to replenish the party's funds. He further requested that £10,000 of this sum be paid, not into the party's regular accounts but to Nadir Dinshaw, an acquaintance of Thorpe's who was resident in the Channel Islands. Thorpe explained that this subterfuge was necessary to deal with a special category of unspecific election expenses. Hayward trusted Thorpe, and sent the £10,000 to Dinshaw who, instructed by Thorpe, passed the money to Holmes.[89] After the October 1974 election Thorpe again requested funds from Hayward, and again asked that £10,000 be sent via the Dinshaw route. Hayward obliged, though this time with more reluctance and after some delay. No accounting of this £20,000 was ever provided; Holmes, Le Mesurier and Deakin all said that it was used to finance a "conspiracy to frighten", although they disagreed as to how much was spent.[93] Thorpe later changed the story he had given Hayward about special categories of election expenses, and said he had deposited the sum with accountants "as an iron reserve against any shortage of funds at any subsequent election." He denied that he had authorised any payment to Newton or to anyone else connected with the case.[94]

Shooting

Newton met Holmes early in October 1975 when, according to Newton, Holmes was given a down payment on a fee of £10,000. Holmes later denied any such transaction, admitting only an agreement that Newton would carry out a frightening operation.[93] On 12 October Newton, calling himself "Peter Keene", drove to Barnstaple in a yellow Mazda car where he approached Scott, claiming to have been hired to protect Scott from a supposed Canadian hit man.[95] This seemed plausible to Scott, who had been beaten up a few weeks earlier,[96] and he agreed to meet "Keene" at a later date. He was sufficiently cautious to ask a friend to make a note of the stranger's car registration number.[97]