Putin Scares World Leaders

PutinScaresWorldLeaders

-

Handy Easy Email and World News Links WebMail

GoogleSearch INLTV.co.uk YahooMail HotMail GMail - news.sky.com/watch-live New York Post nypost.com YouTube

Putin misled by 'yes men' in military afraid to tell him the truth, White House and EU officials say | Reuters

The evolution of the conflict between Russia and Ukraine has brought back the fear of nuclear war and with just cause. Despite the signing of the Non-Proliferation Treaty, the world is still far from a situation of total disarmament.

Many countries have a considerable number of nuclear weapons in their arsenals. In recent years, world peace has been guaranteed by the simple fact that none of them have been used.

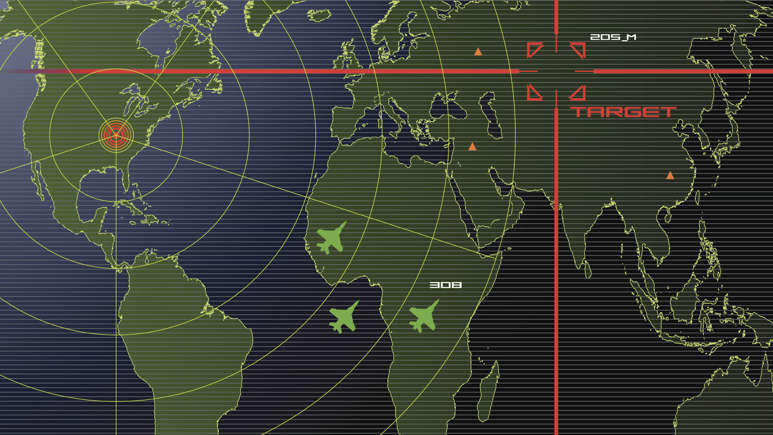

This simulation reveals how a US-Russia nuclear war would play out Story by Zeleb.es

This simulation reveals how a US-Russia nuclear war would play out (msn.com)

The Daily Digest

The Daily DigestThis simulation reveals how a US-Russia nuclear war would play out Story by Zeleb.es

This warning brought back old fears about atomic warfare: What cities would be attacked in such a conflict? How many victims? What would a nuclear war look like?

This simulation reveals how a US-Russia nuclear war would play out (msn.com)

The scenario would involve many countries in the conflict, mainly those where NATO has military bases

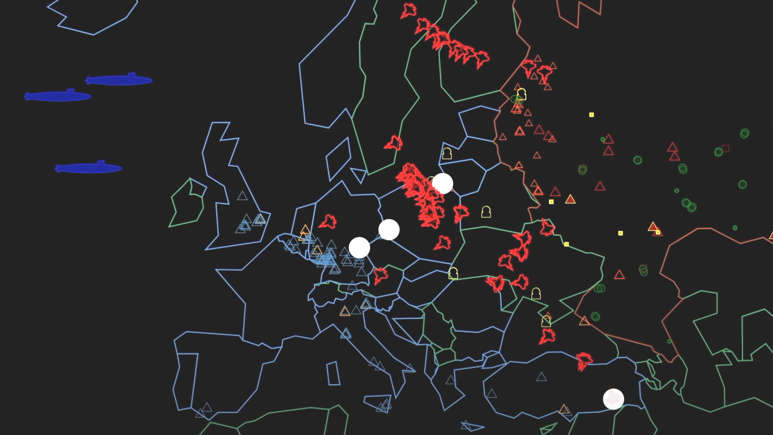

According to the Princeton simulation, Russia would attack first with approximately 300 nuclear warheads and short-range missiles, striking NATO bases and troops. NATO would respond with around 180 warheads carried by aircraft over Russian objectives. Casualties? 2.6 million in the span of three hours.

Image: Screencap from the Princeton University simulation.

With Europe in ruins, NATO launches 600 warheads from US soil and submarine-based missiles aimed at Russian nuclear forces. Russia counterattacks with missiles launched from silos, submarines, and road-mobile vehicles. This conflict continuation would last only 45 minutes and have a toll of up to 3.4 million victims.

Image: Screencap from the Princeton University simulation.

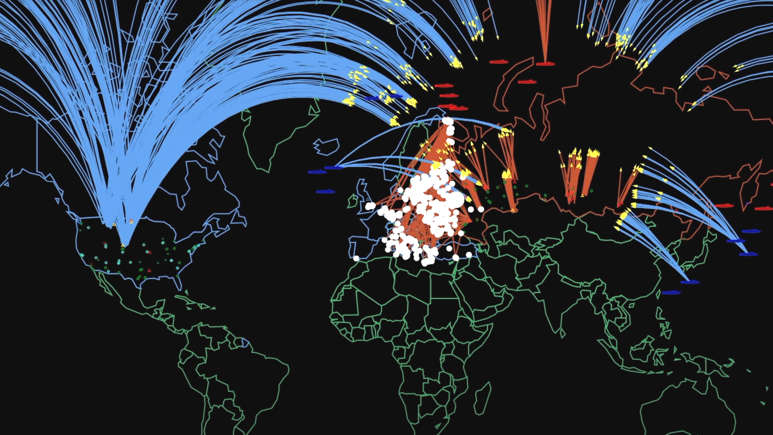

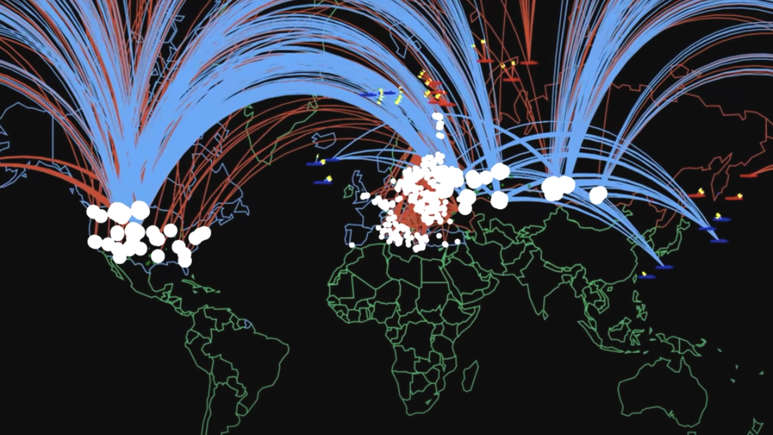

NATO and Russia, following the scenario elaborated by Princeton University, would launch attacks on important economic and population centers to hamper the other side's recovery. Five to ten nuclear warheads would be used for each city. Thermonuclear warfare would kill 85.3 million people in 45 minutes.

Image: Screencap from the Princeton University simulation.

The study estimates that, in total, a nuclear war would immediately affect 91.5 million people, which would cause 34.1 million deaths and 57.4 million wounded within the first four or five hours.

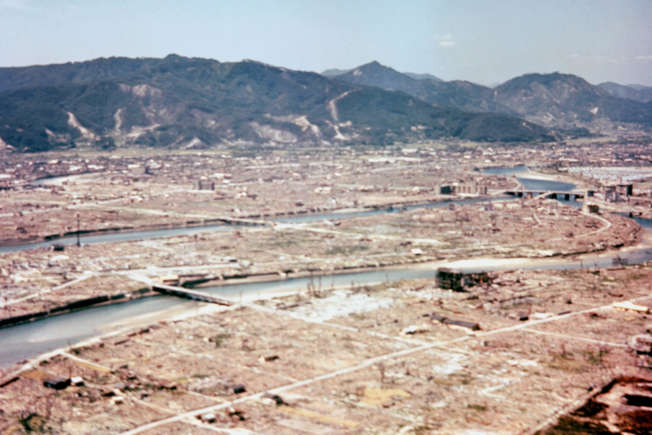

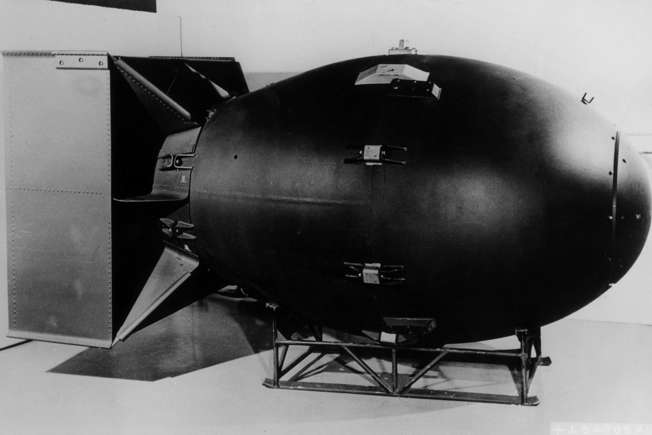

The landscape after the conflict would be something like that: Hiroshima in 1945, when an atomic bomb dropped by the United States leveled an entire city. Over 800,000 people died and some 70,000 were wounded. Those affected by radiation would raise the death toll over the following years.

The Princeton University simulation started off from the idea that, in a conflict between Russia and the United States, Moscow would strike with nuclear weapons first.

If the United States is the first to start a nuclear strike, the result would be more or less the same. The scenario presented is based on how the NATO defensive strategy is thought out in case of Russian aggression.

There really isn't much that can be done during a nuclear war: Everything is programmed and there's virtually no time to stop Armageddon.

The fragile principle that held together peace during the Cold War between the United States and Russia was Mutual Assured Destruction, also known as MAD. The idea was that no side would dare to push the button since nobody would win.

The phrase is attributed to nuclear scientist John von Neumann, seeing here receiving the Freedom Medal from President Eisenhower in 1956. The German-born scientist translated the idea into mathematic terms as 1 + 1 = 0.

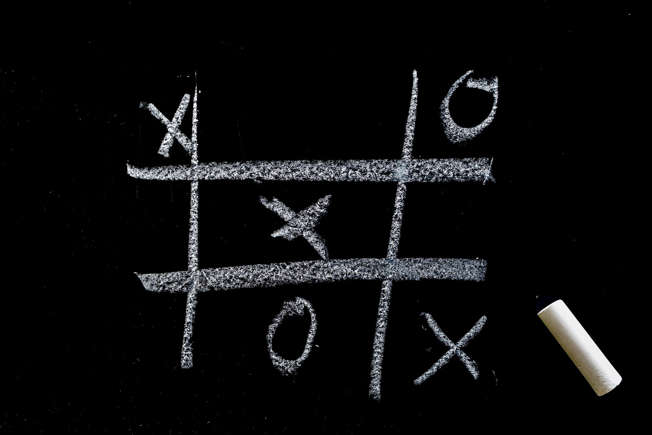

Film buffs might remember The Doomsday Machine from 'Dr. Strangelove', a Soviet supercomputer that would automatically start a nuclear strike in case the US started a nuclear war. A 2009 piece by NPR reveals that such a system was real and that it was still functioning.

A relatively more recent example was the 1983 John Badham movie 'WarGames'. The premise rests on the tension on how to stop a military supercomputer once it has started to run its attack protocol.

'WarGames' spoilers ahead: The supercomputer programmed to start the nuclear war plays tic-tac-toe against itself and figures out that nobody can win a game like that.

However, life isn't a Hollywood movie, especially when it comes to war. When a conflict begins, it's hard to say how it will end. Just look at recent cases in Iraq or Afghanistan.

The threat of the nuclear apocalypse loomed over the 1980s. Is the world regressing to this scenario? Will humanity go from a global pandemic to a new world war?

24 June 2023 Russia-Ukraine war

Ukraine conflict: Who's in Putin's inner circle and running the war? - BBC News

Ukraine conflict: Who's in Putin's inner circle and running the war? - BBC News

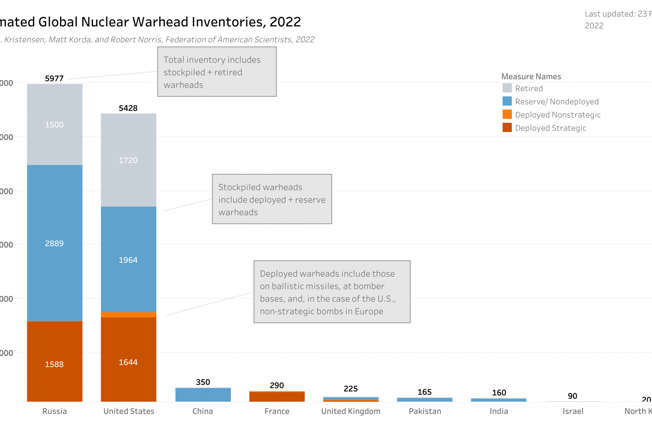

According to data from the Federation of American Scientists, in 2022, there are about 12,700 nuclear warheads worldwide.

"Not a single day has passed where some deputy minister or some deputy governor [has not been] raided or arrested or so on. They're under 24/7 FSB security service surveillance, all of them, if they make one wrong move it's immediately reported and they could face, basically, jail time."

Nine nations own these weapons: Russia, United States, France, United Kingdom, Israel, Pakistan, India, China, and North Korea.

Weapons of mass destruction you won't believe are being created

Weapons of mass destruction (WMD) have been developed, produced, and used on some occasions. The nuclear bomb was a game changer when it came to the amount of damage a WMD could inflict, but technology has evolved, and so have WMDs. Cyber warfare is nothing new, nor is the use of biological weapons, but these are much more sophisticated now. Plus, we have a few new weapons, both hypothetical and real ones, that are worth mentioning.

When it comes to the development of such weapons, countries with enormous military budgets like the US and Israel are at the forefront. The war between Israel and Palestine that broke out in October 2023 has sadly seen some of their advanced technology put to use. As Israel prepares for a ground invasion of Gaza, they are formulating a plan to take over the underground tunnels that have been built under the tiny enclave. As they enter the tunnels, they are reportedly going to employ "sponge bombs" to block off passageways from which they might be ambushed. These bombs don't actually explode, but instead combine two chemical compounds which creates a burst of foam. The foam quickly expands and hardens, sealing off tunnels and exits.

While the tunnels are used by Hamas and other Palestinian armed groups, they are also essential lifelines being used to smuggle essential supplies to the civilians trapped inside Gaza. The enclave has been blockaded on all sides, with no access to food, water, electricity, or medical supplies. Israel has yet to commence its ground operation but has dropped an estimated 6,000 bombs per day on Gaza since the outbreak of the conflict.

In this gallery, we look at what you need to know about the future of weapons of mass destruction. Click on to learn more.

What Putin Fears Most | Journal of Democracy

https://www.

Russian president Vladimir Putin wants you to believe that NATO is responsible for his February 24 invasion of Ukraine—that rounds of NATO enlargement made Russia insecure, forcing Putin to lash out. This argument has two key flaws. First, NATO has been a variable and not a constant source of tension between Russia and the West. Moscow has in the past acknowledged Ukraine’s right to join NATO; the Kremlin’s complaints about the alliance spike in a clear pattern after democratic breakthroughs in the post-Soviet space. This highlights a second flaw: Since Putin fears democracy and the threat that it poses to his regime, and not expanded NATO membership, taking the latter off the table will not quell his insecurity. His declared goal of the invasion, the “denazification” of Ukraine, is a code for his real aim: antidemocratic regime change.

Russia’s brutal invasion of Ukraine has ignited the largest war in Europe since the Second World War, indiscriminately spilling the blood of thousands of Ukrainian soldiers and innocent civilians. Russian president Vladimir Putin wants you to believe that NATO is to blame. He has frequently claimed that NATO expansion—not the 200,000 Russian soldiers and sailors attacking Ukraine’s ports, airfields, roads, railways, and cities—is the central driver of this crisis. Following John Mearsheimer’s provocative 2014 Foreign Affairs article arguing that “the Ukraine crisis is the West’s fault,” the narrative of Russian backlash against NATO expansion has become a dominant framework for explaining—if not justifying—Moscow’s ongoing war against Ukraine.1 This notion has been repeated not only in Moscow but in the United States, Europe, and elsewhere by politicians, analysts, and writers. Multiple rounds of enlargement, they argue, exacerbated Russia’s sense of insecurity as NATO forces crept closer to Russia’s borders, finally provoking Putin to lash out violently, first by invading Georgia in 2008, then Ukraine in 2014, and now a second, likely far larger, invasion of Ukraine today. By this telling, the specter of Ukraine’s NATO membership points both to the cause of the conflict and its solution: Take membership off the table for Ukraine, so the argument goes, and future wars will be prevented.

This argument has two flaws, one about history and one about Putin’s thinking. First, NATO expansion has not been a constant source of tension between Russia and the West, but a variable. Over the last thirty years, the salience of the issue has risen and fallen not primarily due to waves of NATO expansion, but instead as a result of waves of democratic expansion in Eurasia. In a very clear pattern, Moscow’s complaints about the alliance spike after democratic breakthroughs. While the tragic invasions and occupations of Georgia and Ukraine have secured Putin a de facto veto over their NATO aspirations, since the alliance would never admit a country under partial occupation by Russian forces, this fact undermines Putin’s claim that the current invasion is aimed at NATO membership. He has already blocked NATO expansion for all intents and purposes, thereby revealing that he wants something far more significant in Ukraine today: the end of democracy and the return of subjugation. On February 24, in an hour-long, meandering rant explaining his decision to invade, he said so directly.

This reality highlights the second flaw: Because the primary threat to Putin and his autocratic regime is democracy, not NATO, that perceived threat would not magically disappear with a moratorium on NATO expansion. Putin would not stop seeking to undermine democracy and sovereignty in Ukraine, Georgia, or the region as a whole if NATO stopped expanding. As long as citizens in free countries exercise their democratic rights to elect their own leaders and set their own course in domestic and foreign politics, Putin will continue to try to undermine them. Putin’s declared goal of “denazification” in Ukraine is a code word for regime change—antidemocratic regime change.

How We Got Here

To be sure, NATO and its expansion have always been sources of tension in U.S.-Soviet and U.S.-Russian relations. Two decades ago, one of us coauthored (with James Goldgeier) a book on U.S-Russia relations, Power and Purpose, that includes a chapter called “NATO Is a Four-Letter Word.”2 To varying degrees, Kremlin leaders Mikhail Gorbachev, Boris Yeltsin, Putin, and Dmitri Medvedev have expressed concerns about the expansion of the alliance.

Since its founding in 1949, NATO has kept its door open to new members who meet the criteria for admission. After the collapse of the USSR in 1991, no one should be surprised that countries formerly annexed, subjugated, and invaded by the Soviet Union might seek closer security ties to the West. The United States and other NATO allies have worked hard not to deny the aspirations of those newly free societies while also partnering with Russia on European and other security issues. They have sometimes had success and sometimes not.

Many of those who blame the current Ukraine conflict on NATO overlook the fact that in the thirty years since the end of the Cold War, Moscow’s rejection of NATO expansion has veered in different directions at different times.

When President Boris Yeltsin agreed to sign the Russia-NATO Founding Act in 1997, Russia and the alliance codified into this agreement a comprehensive agenda of cooperation. At the signing ceremony Yeltsin declared,

What is also very important is that we are creating the mechanisms for consultations and cooperation between Russia and the Alliance. And this will enable us—on a fair, egalitarian basis—to discuss, and when need be, pass joint decisions on major issues relating to security and stabilities, those issues and those areas which touch upon our interests.3

In 2000 while visiting London, Putin, then serving as acting Russian president, even suggested that Russia could join NATO someday:

Why not? Why not . . . I do not rule out such a possibility . . . in the case that Russia’s interests will be reckoned with, if it will be an equal partner. Russia is a part of European culture, and I do not consider my own country in isolation from Europe . . . Therefore, it is with difficulty that I imagine NATO as an enemy.4

Why would Putin want to join an alliance allegedly threatening Russia?

After the 9/11 terrorist attacks, U.S. president George W. Bush and Putin forged a close, cooperative relationship to fight a common enemy: terrorism. At the time, Putin was focused on cooperation with NATO, not confrontation. The only time the alliance has ever invoked Article 5 on collective defense was to support a NATO intervention in Afghanistan, an action that Putin supported at the UN Security Council. He then followed up this diplomatic support with concrete military assistance for the alliance, including helping the United States to establish military bases in Uzbekistan and Kyrgyzstan. If NATO was always a threat to Russia and its “sphere of influence,” why did Putin facilitate the opening of these bases in the former Soviet Union?

During his November 2001 visit to the United States, Putin struck a realistic but cooperative tone:

We differ in the ways and means we perceive that are suitable for reaching the same objective . . . [But] one can rest assured that whatever final solution is found, it will not threaten . . . the interests of both our countries and of the world.5

In an interview that month, Putin declared,

Russia acknowledges the role of NATO in the world of today, Russia is prepared to expand its cooperation with this organization. And if we change the quality of the relationship, if we change the format of the relationship between Russia and NATO, then I think NATO enlargement will cease to be an issue—will no longer be a relevant issue.6

When NATO announced in 2002 its plan for a major (and last big) wave of expansion that would include three former Soviet republics—Estonia, Latvia, and Lithuania—Putin barely reacted. He certainly did not threaten to invade any of the countries to keep them out of NATO. Asked specifically in late 2001 whether he opposed the Baltic states’ membership in NATO, he stated, “We of course are not in a position to tell people what to do. We cannot forbid people to make certain choices if they want to increase the security of their nations in a particular way.”7

Putin even maintained the same attitude when it was a question of Ukraine someday entering the Atlantic Alliance. In May 2002, when asked for his views on the future of Ukraine’s relations with NATO, Putin dispassionately replied,

I am absolutely convinced that Ukraine will not shy away from the processes of expanding interaction with NATO and the Western allies as a whole. Ukraine has its own relations with NATO; there is the Ukraine-NATO Council. At the end of the day, the decision is to be taken by NATO and Ukraine. It is a matter for those two partners.8

A decade later, under President Medvedev, Russia and NATO were cooperating once again. At the 2010 NATO summit in Lisbon, Medvedev declared,

The period of distance in our relations and claims against each other is over now. We view the future with optimism and will work on developing relations between Russia and NATO in all areas . . . [as they progress toward] a full-fledged partnership.9

At that summit, he even floated the possibility of Russia-NATO cooperation on missile defense. Complaints about NATO expansion never arose.

From the end of the Cold War until Putin’s invasion of Ukraine in 2014, NATO in Europe was drawing down resources and forces, not building them up. Even while expanding membership, NATO’s military capacity in Europe was much greater in the 1990s than in the 2000s. During this same period, Putin was spending significant resources to modernize and expand Russia’s conventional forces deployed in Europe. The balance of power between NATO and Russia was shifting in favor of Moscow.

These episodes of substantive Russia-NATO cooperation undermine the argument that NATO expansion has always and continuously been the driver of Russia’s confrontation with the West during the last three decades. The historical record simply does not support the thesis that an expanding NATO bears sole blame for Russian antagonism with the West and Moscow’s aggression against Ukraine since 2014. Rather, we must look elsewhere to understand the genuine source of Putin’s hostility to Ukraine and its Western partners.

The more serious cause of tensions has been a series of democratic breakthroughs and popular protests for freedom in postcommunist countries throughout the 2000s, which many, including Putin, refer to as the “color revolutions.”10 Putin believes that Russian national interests have been threatened by what he portrays as U.S.-supported coups. After each of them—Serbia in 2000, Georgia in 2003, Ukraine in 2004, the Arab Spring in 2011, Russia in 2011–12, and Ukraine in 2013–14—Putin has pivoted to more hostile policies toward the United States, and then invoked the NATO threat as justification for doing so.

Boris Yeltsin never supported NATO expansion but acquiesced to the first round of expansion in 1997 because he believed that his close ties to President Bill Clinton and the United States were not worth sacrificing over this comparatively smaller matter. Through NATO’s Partnership for Peace program and especially the NATO-Russia Founding Act, Clinton and his team made a considerable effort to keep U.S.-Russian relations positive while at the same time managing NATO expansion. The 1999 NATO bombing of Serbia to stop ethnic cleansing in Kosovo severely tested that strategy but survived in part because Clinton gave Yeltsin and Russia a role in the negotiated solution. When the first postcommunist color revolution overthrew Slobodan Miloševiæ a year later, Russia’s new president, Putin, deplored the act but did not overreact. At that time, he still entertained the possibility of cooperation with the West, including NATO.

Yet the next round of democratic expansion in the post-Soviet world, the 2003 Rose Revolution in Georgia, escalated U.S.-Russian tensions significantly. Putin blamed the United States directly for assisting this democratic breakthrough and helping to install someone whom he saw as a pro-American puppet, President Mikheil Saakashvili. Immediately after the Rose Revolution, Putin sought to undermine Georgian democracy, ultimately invading in August 2008 and recognizing two Georgian regions—Abkhazia and South Ossetia—as independent states. U.S.-Russian relations reached a new post-Soviet low in 2008.

A year after the Rose Revolution, the most consequential democratic expansion in the post-Soviet world, the Orange Revolution, erupted in Ukraine in 2004.11 In the years prior to that democratic breakthrough, Ukraine’s foreign-policy orientation under President Leonid Kuchma was relatively balanced between east and west, but with gradually improving ties between Kyiv and Moscow. That changed when a falsified presidential election in late 2004 brought hundreds of thousands of Ukrainians into the streets, eventually sweeping away Kuchma’s—and Putin’s—handpicked successor, Viktor Yanukovych.12 Instead, the prodemocratic and pro-Western Orange Coalition led by President Viktor Yushchenko and Prime Minister Yuliya Tymoshenko took power.

Compared to Serbia in 2000 or Georgia in 2003, Ukraine’s Orange Revolution was a much larger threat to Putin. First, the Orange Revolution occurred suddenly and in a much bigger and more strategic country on Russia’s border. The abrupt pivot to the West by Yushchenko and his allies left Putin facing the prospect that he had “lost” a country on which he placed tremendous symbolic and strategic importance.

To Putin, the Orange Revolution undermined a core objective of his grand strategy: to establish a privileged and exclusive sphere of influence across the territory that once comprised the Soviet Union.13 Putin believes in spheres of influence—that as a great power, Russia has a right to veto the sovereign political decisions of its neighbors. Putin also demands exclusivity in his neighborhood: Russia can be the only great power to exercise such privilege (or even to develop close ties) with these countries. This position has hardened significantly since Putin’s conciliatory stance of 2002 as Russia’s influence in Ukraine has waned and Ukraine’s citizens have repeatedly signaled their desire to escape Moscow’s grasp. Subservience is now required. As Putin explained in a recent article, in his view Ukrainians and Russians are “one people” whom he is seeking to reunite, even if through coercion.14 For Putin, therefore, the 2004 “loss” of Ukraine to the West marked a major negative turning point in U.S.-Russian relations that was far more salient than the second wave of NATO expansion that was completed the same year.

Second, those Ukrainians who rose up in defense of their freedom were, in Putin’s own assessment, Slavic brethren with close historical, religious, and cultural ties to Russia. If it could happen in Kyiv, why not in Moscow? Several years later, it almost did occur in Russia when a series of mass protests erupted in Moscow, St. Petersburg, and other cities in the wake of fraudulent parliamentary elections in December 2011.15 They were the largest protests in Russia since 1991, the year the Soviet Union collapsed. For the first time in Putin’s decade-plus in power, ordinary Russians showed themselves to have both the will and the capability to threaten his grip on power.16 That popular uprising in Russia occurred the same year as the Arab Spring and was followed by Putin’s return to the Kremlin as president for a third term in 2012. The combination of these mass protests and Putin’s reelection as president caused another major negative turn in U.S.-Russian relations and ended the “reset” launched by Presidents Barack Obama and Dmitri Medvedev in 2009.17 Democratic mobilization, first in the Middle East and then across Russia—not NATO expansion—ended this last chapter of U.S.-Russian cooperation. There have been no new chapters of cooperation since.

U.S.-Russian relations deteriorated even further in 2014, again because of new democratic expansion, not NATO expansion. The next democratic mobilization to threaten Putin happened again in Ukraine in 2013–14. After the Orange Revolution in 2004, Putin did not invade Ukraine, but wielded other instruments of influence to help his protégé, Viktor Yanukovych, narrowly win the Ukrainian presidency six years later. Yanukovych, however, turned out not to be a loyal Kremlin servant, but tried to cultivate ties with both Russia and the West. Putin finally compelled Yanukovych to make a choice, and the Ukrainian president chose Russia in November 2013 when he reneged on signing an EU association agreement in favor of pursing membership in Russia’s Eurasian Economic Union.

To the surprise of everyone in Moscow, Kyiv, Brussels, and Washington, Yanukovych’s decision to scuttle this agreement with the EU triggered mass demonstrations in Ukraine again, with hundreds of thousands of Ukrainians pouring into the streets in what would become known as the EuroMaidan or “Revolution of Dignity” to protest Yanukovych’s turn away from the democratic West. The street protests lasted several weeks, punctuated tragically by the killing of dozens of peaceful protestors by Yanukovych’s government, the eventual collapse of that government and Yanukovych’s flight to Russia in February 2014, and a new pro-Western government taking power in Kyiv. Putin had “lost” Ukraine for the second time in a decade, again because of democratic regime change.

But this time, Putin struck back with military force to punish the alleged U.S.-backed, neo-Nazi usurpers in Kyiv. Russian armed forces seized Crimea; Moscow later annexed the Ukrainian peninsula. Putin also provided money, equipment, and soldiers to back separatists in eastern Ukraine, fueling a simmering eight-year war in Donbas that claimed the lives of approximately fourteen-thousand people. After invading—not before—Putin amped up his criticisms of NATO expansion to justify his belligerent actions.

In response to this second Ukrainian democratic revolution, Putin concluded that cooptation through elections and other nonmilitary means had to be augmented with greater coercive pressure, including military intervention. Since the Revolution of Dignity, Putin has waged an unprecedented assault against Ukraine’s democracy using a full spectrum of military, political, informational, social, and economic weapons in an attempt to destabilize and eventually topple Ukraine’s democratically elected government.18 Ukraine’s relationship with NATO and the United States was just a symptom of what Putin believes is the underlying disease: a sovereign, democratic Ukraine.

Putin’s Real Casus Belli: Ukrainian Democracy

Amazingly, eight years of unrelenting Russian pressure did not break Ukraine’s democracy. Just the opposite. After Putin’s annexation and ongoing support for the war in Donbas, Ukrainians are now more united across ethnic, linguistic, and regional divides than at any other point in Ukrainian history. In 2019, Volodymyr Zelensky won the Ukrainian presidency in a landslide election, winning popular support in every region of the country. Not surprisingly, Putin’s war in eastern Ukraine also has fueled greater enthusiasm for joining NATO among Ukrainians.

In February 2022, Putin embarked on a new strategy for ending Ukrainian democracy: massive military intervention. Putin claims that his purpose is to stop NATO expansion. But that is a fiction. Nothing in Ukraine-NATO relations has changed in the past year. It is true that Ukraine aspires to join NATO someday. (The goal is even embedded in the Ukrainian constitution.) But while NATO leaders have remained committed to the principle of an open-door policy, they also clearly stated prior to the war that Ukraine was not yet qualified to join. Putin’s casus belli is his own invention.

On the eve of his invasion, Putin’s strategy to undermine Ukrainian democracy looked as if it might succeed without military force. The very threat of war did significant damage to the Ukrainian economy and fueled new divisions among Ukraine’s political parties over how Zelensky handled the leadup to the crisis. Some argued that Zelensky should have created a new grand coalition or unity government; others lamented his alleged inadequate preparations for war. And some claimed that Zelensky showed his diplomatic inexperience by arguing with U.S. president Joe Biden about the probability of a Russian invasion at a time when unity with the West was most needed.

But an impatient and angry Putin could not wait anymore. He attacked with the full might of the Russian armed forces. As this essay goes to print, the war is still raging.

Putin’s strategy has backfired thus far. Contrary to his expectations, Putin’s use of force has strengthened Ukrainian democracy, not weakened it. His decision to invade Ukraine has united Ukrainians and strengthened Zelensky’s popularity and image as a leader of the nation. While Putin has remained isolated from his subjects and even his own courtiers while his bombs wreak devastation in a far-off land, the charismatic Zelensky has vowed to stay in Kyiv with his soldiers and fight for Ukraine’s democratic future, rallying public opinion in Ukraine and around the world. Putin may still believe that there is no such thing as a Ukrainian nation, as he has claimed on multiple occasions. But just as warfare has forged national identities for centuries, Russia’s aggression has galvanized a Ukrainian people who will forevermore turn their backs on Muscovy’s autocracy, choosing instead to embrace the universal value of freedom—freedom from Russian domination, freedom to choose their own destiny, freedom to live in peace.

But despite early Ukrainian successes on the battlefield, the long-term survival of Ukraine’s democracy hangs in the balance. Putin’s continued bellicose rhetoric and rejection of any serious attempts to negotiate a ceasefire suggest that Moscow’s assault will continue unabated. Russia’s initial military operations suggest that Putin envisioned a blitzkrieg invasion from multiple fronts that would face little resistance and rapidly encircle Kyiv, resulting in Zelensky’s forcible removal from power. New elections held at gunpoint would then deliver Putin his desired puppet government, just as they did in post–World War II Eastern Europe in the shadow of Soviet tanks. In one Ukrainian city, Melitopol, in a facsimile of Stalin’s methods in Eastern Europe after 1945, Russia’s occupying forces have already removed the mayor and installed a Moscow puppet. At the time of this writing, however, Russia’s military has been bogged down by fierce Ukrainian resistance and is now settling in for the unpleasant prospect of a long, bloody slog across miles of inhospitable Ukrainian territory. Russia’s armies will be treated by Ukrainians as the occupiers of 1941, not the liberators of 1945. It is too early to predict the outcome of this gruesome war. But despite the Russian army’s poor performance so far, there is no evidence to suggest that Putin has abandoned his objective to remove Zelensky from power and subjugate Ukraine to Moscow’s control.

Putin may dislike NATO expansion, but he is not genuinely frightened by it. Russia has the largest army in Europe, engorged by two decades of lavish spending. NATO is a defensive alliance. It has never attacked the Soviet Union or Russia, and it never will. Putin knows that. But Putin is threatened by a flourishing democracy in Ukraine. He cannot tolerate a successful and democratic Ukraine on Russia’s border, especially if the Ukrainian people also begin to prosper economically. That would undermine the Kremlin’s own regime stability and proposed rationale for autocratic state leadership. Just as Putin cannot allow the will of the Russian people to guide Russia’s future, he cannot allow the people of Ukraine, who have a shared culture and history, to realize the prosperous, independent, and free future that they have voted and fought for.

Although the chance of a stable ceasefire seems remote today, unprecedented sanctions and growing public dissent within Russia could, in theory, force Putin to the negotiating table. The fog of war is dense. But regardless of where the Russian invaders are stopped—be it Luhansk and Donetsk or Kharkiv, Mariupol, Kherson, Odesa, Kyiv, or Lviv—the Kremlin will remain committed to undermining Ukrainian (and Georgian, Moldovan, Armenian, and the list goes on) democracy and sovereignty for as long as Putin remains in power and maybe longer if Russian autocracy continues. And the Ukrainian people have already proved their mettle: They will fight for their democracy until the day Russian forces leave Ukraine.

NOTES

1. John J. Mearsheimer, “Why the Ukraine Crisis Is the West’s Fault: The Liberal Delusions That Provoked Putin,” Foreign Affairs 93 (September–October 2014): 77.

2. James M. Goldgeier and Michael McFaul, Power and Purpose: U.S. Policy Toward Russia After the Cold War (Washington D.C.: Brookings Institution Press, 2003).

3. White House Office of the Press Secretary, “NATO-Russia Founding Act Signing,” 27 May 1997, https://

4. David Hoffman, “Putin Says ‘Why Not?’ to Russia Joining NATO,” Washington Post,6 March 2000, www.washingtonpost.com/

5. Bob Kemper, “Bush, Putin Downplay Differences,” Chicago Tribune, 16 November 2001, www.chicagotribune.com/

6. “Transcript of Robert Siegel Interview with Vladimir Putin,” NPR, 15 November 2001, https://legacy.npr.org/

7. “Transcript of Robert Siegel Interview with Vladimir Putin.”

8. “Press Statement and Answers to Questions at a Joint News Conference with Ukrainian President Leonid Kuchma,” President of Russia, 17 May 2002, http://en.kremlin.ru/

9. “News Conference Following NATO-Russia Council Meeting,” President of Russia, 20 November 2010, http://en.kremlin.ru/

10. Michael McFaul, “Transitions from Postcommunism,” Journal of Democracy 16 (July 2005): 5–19.

11. Anders Åslund and Michael McFaul, Revolution in Orange: The Origins of Ukraine’s Democratic Breakthrough (Washington, D.C.: Carnegie Endowment for International Peace, 2006).

12. McFaul, “Transitions from Postcommunism,” 5.

13. Robert Person, “Four Myths About Russian Grand Strategy,” Center for Strategic and International Studies, 22 September 2020, https://www.csis.org/

14. Vladimir Putin, “On the Historical Unity of Russians and Ukrainians,” President of Russia, 12 July 2021, http://en.kremlin.ru/

15. Denis Volkov, “Putinism Under Siege: The Protesters and the Public,” Journal of Democracy 23 (July 2012): 55–62.

16. Robert Person, “Balance of Threat: The Domestic Insecurity of Vladimir Putin,” Journal of Eurasian Studies 8, no. 1 (2017): 44–59.

17. Michael McFaul, From Cold War to Hot Peace: An American Ambassador in Putin’s Russia (New York: Houghton Mifflin Harcourt, 2018).

18. Taras Kuzio, Putin’s War Against Ukraine: Revolution, Nationalism, and Crime (CreateSpace Independent Publishing Platform, 2017).

The views expressed in this essay are the authors’ own and do not reflect the official position of the U.S. Army, Department of Defense, or U.S. Government.

About the Authors

Robert Person

Robert Person is associate professor of international relations at the U.S. Military Academy, director of its international affairs curriculum, and faculty affiliate at its Modern War Institute. His next book, Russia’s Grand Strategy in the 21st Century, is forthcoming. His Twitter is @RTPerson3.

View all work by Robert Person

Michael McFaul

Michael McFaul, former U.S. ambassador to Russia, is professor of political science at Stanford University, director of the Freeman Spogli Institute for International Studies, and Peter and Helen Bing Senior Fellow at the Hoover Institution. His most recent book is From Cold War to Hot Peace: An American Ambassador in Putin’s Russia (2018).

View all work by Michael McFaul

Photo: Federation of American Scientists

Putin misled by 'yes men' in military afraid to tell him the truth, White House and EU officials say | Reuters

March 31, 20228

WASHINGTON, March 30 (Reuters) - Russian President Vladimir Putin was misled by advisers who were too scared to tell him how poorly the war in Ukraine is going and how damaging Western sanctions have been, White House and European officials said on Wednesday.

Russia's Feb. 24 invasion of its southern neighbor has been halted on many fronts by stiff resistance from Ukrainian forces who have recaptured territory even as civilians are trapped in besieged cities.

“We have information that Putin felt misled by the Russian military, which has resulted in persistent tension between Putin and his military leadership,” Kate Bedingfield, White House communications director, told reporters during a press briefing.

“We believe that Putin is being misinformed by his advisers about how badly the Russian military is performing and how the Russian economy is being crippled by sanctions because his senior advisors are too afraid to tell him the truth,” she said.

The U.S. was putting forward this information now to show “this has been a strategic error for Russia,” she said.

The Kremlin made no immediate comment about the assertions after the end of the working day in Moscow, and the Russian embassy in Washington did not immediately reply to a request for comment.

Washington's decision to share its intelligence more publicly reflects a strategy it has pursued since before the war began. In this case, it could also complicate Putin's calculations, a second U.S. official said, adding, "It's potentially useful. Does it sow dissension in the ranks? It could make Putin reconsider whom he can trust."

Russian President Vladimir Putin chairs a meeting with members of the Security Council via a video link at the Novo-Ogaryovo state residence outside Moscow, Russia March 24, 2022. Sputnik/Mikhail Klimentyev/Kremlin via REUTERS/File Photo Acquire Licensing Rights

One senior European diplomat said the U.S. assessment was in line with European thinking. "Putin thought things were going better than they were. That's the problem with surrounding yourself with 'yes men' or only sitting with them at the end of a very long table," the diplomat said.

Russian conscripts were told they were taking part in military exercises, but had to sign a document before the invasion that extended their duties, two European diplomats said.

"They were misled, badly trained and then arrived to find old Ukrainian women who looked like their grandmothers yelling at them to go home," one of the diplomats added.

There were no indications at the moment that the situation could foster a revolt among the Russian military, but the situation was "unpredictable" and Western powers "would hope that unhappy people would speak up," the senior European diplomat said.

Military analysts say Russia has reframed its war goals in Ukraine in a way that may make it easier for Putin to claim a face-saving victory despite a woeful campaign in which his army has suffered humiliating setbacks. read more

Russian forces bombarded the outskirts of the capital Kyiv and the besieged city of Chernihiv in northern Ukraine on Wednesday, a day after Russia promised to scale down military operations in both cities in what the West dismissed as a ploy to regroup by invaders suffering heavy losses. read more

Russia says it is carrying out a "special operation" to disarm and "denazify" its neighbor. Western countries say Moscow launched an unprovoked invasion.

Reporting by Steve Holland and Andrea Shalal; Writing by Doina Chiacu; Editing by Chizu Nomiyama and Jonathan Oatis

These are huge numbers, especially if we compare the amount of nukes Russia has with those of other NATO countries. Putin, in fact, has more nuclear warheads available to him than all the NATO countries put together.

Of the 5,977 Russian nuclear warheads, however, 1,500 are obsolete and ready for decommissioning.

According to the Federation of American Scientists, there are still 1,588 nukes in Russia that are ready to be used on a moments notice - on Vladimir Putin's command.

The United States has a good idea of how many strategic nuclear weapons are in Russia's arsenal because both Washington and Moscow must disclose this information under the terms of New START, the last remaining arms control treaty.

According to the Bulletin of the Atomic Scientists, the Russian arsenal includes a total of 2.565 strategic warheads. Strategic nuclear weapons are the most destructive of the two kinds of nuclear weapons.

However, Moscow also has a large number of tactical nuclear weapons, with less destructive potential compared to strategic ones (up to 50 kilotons) and with a shorter range.

The Bulletin of the Atomic Scientists states that Russia has 1,912 non-strategic warheads which are being held in reserve.

Putin's absurb, angry spectacle will be a turning point in his long reign

Analysis: This was a supreme leader marshalling his minions for a decision that will change the security architecture in Europe and may well lead to horrific war

Sitting alone at a desk in a grand, columned Kremlin room, Vladimir Putin looked across an expanse of parquet floor at his security council and asked if anyone wished to express an alternative opinion.

He was met with silence.

A few hours later, the Russian president appeared on state television to give an angry, rambling lecture about Ukraine, a country that in Putin’s telling had become “a colony with a puppet regime”, and had no historical right to exist.

Putin’s double bill, which was immediately followed by the signing of an agreement on Russian recognition of the two proxy states in east Ukraine as independent entities, is likely to go down in history as one of the major turning points in his 22-years-and-counting rule over Russia.

This was not a politician convening his team for discussions, this was a supreme leader marshalling his minions and ensuring collective responsibility for a decision that, at minimum, will change the security architecture in Europe, and may well lead to a horrific war that consumes Ukraine.

Putin appeared genuinely angry and passionate in his speech, which he almost certainly wrote himself.

Belarus should face same sanctions as Russia in event of invasion, says EUIn a symbolic sign of his increasing isolation, with no equals who can talk back to him or debate ideas, Putin has recently taken to meeting politicians, including his own ministers, across ostentatiously large tables, apparently as a Covid precaution. But at the security council meeting on Monday, when a long table for once would have seemed appropriate, Putin sat alone, surveying his subordinates from absurdly far away, as they squirmed awkwardly in chairs waiting their turn to be grilled by the boss.

From behind his desk, frequently smirking, Putin listened one-by-one to his security council. The body contains some of the few people who have Putin’s ear, but even some of them appeared overawed by the situation and nervous at fluffing their lines.

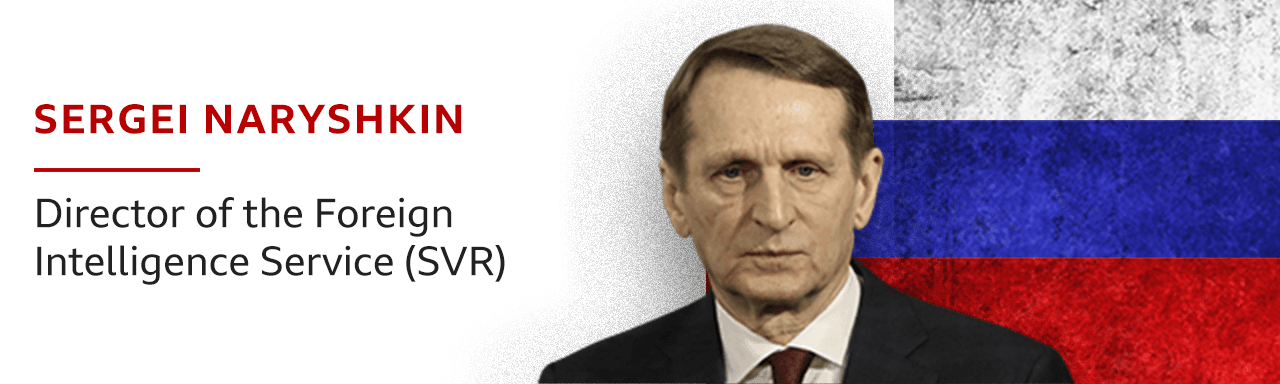

Sergei Naryshkin, the hawkish head of Russia’s spy service, known for making aggressively anti-western statements, stuttered uncomfortably as Putin grilled him on whether he supported the decision.

“Speak directly!” Putin snapped, twice.

Eventually, when he was able to get the words out, Naryshkin said he supported “the LNR and DNR becoming part of Russia.” Putin told him that wasn’t the subject of the discussion; it was only recognition being weighed up.

'Speak plainly!': Putin has tense exchange with his spy chief – video

Some suggested this might have been a carefully scripted encounter to show the West what other options might be available, but Naryshkin’s genuinely flustered expression suggested otherwise.

It is hard to tell whether or not Putin had decided his plan for Ukraine months ago, or whether he has been making plans on the hop, but it was certainly clear that the decision on recognition had been taken well before this strange, stage-managed event.

There was very little exchange of opinion, and the idea that it was all spontaneous was further undermined by the fact that closeups of the watches of certain participants appeared to suggest that the “live” broadcast had in fact been filmed several hours earlier.

This did not stop Putin specifically emphasising that the event really was a frank exchange of views.

“Every one of you knows, and I specially want to underline it … I did not discuss any of this with you before. I did not ask your opinion before. And this is happening spontaneously, because I wanted to hear your opinions without any preliminary preparation,” he said.

The appearance of Putin just a few hours later with his long, pre-prepared and wide-ranging speech made the claim this was all a real-time decision-making process even more implausible.

Many of Putin’s team give the impression of genuinely believing the propaganda narrative Russia has built to justify its continuing aggression against Ukraine. Valentina Matviyenko, the only woman on the security council, gave an elongated harangue cobbled together from the more outlandish talking points of Russian news bulletins: innocent Russia facing down the nefarious west, which was backing the “genocidal” Kyiv regime.

UK says ‘serious doubts’ exist within Russian military about invading Ukraine

Not everyone was so enthusiastic: the prime minister, Mikhail Mishustin, spoke briefly and drily, looking visibly uncomfortable. Not willing to let him off the hook without swearing fealty to the decision that was already inevitably on the way, Putin asked him directly whether he supported it; Mishustin mumbled that he did. Everyone was now publicly on record as supporting this move; nobody will be able to weasel out of it later and claim they put up a fight.

The recognition decision answers some questions but others remain. There is a chance Putin may simply recognise the two republics “as they are”. This, after months of apocalyptic scenarios, would probably be privately accepted as a good outcome by Ukraine and the west.

But it seems likely that Putin has much more in mind than simply taking a nibble out of Ukraine’s east and taking formal responsibility for territories he already de facto controlled.

Putin’s final words, that if Kyiv did not stop the violence they would bear responsibility for the “ensuing bloodshed”, were ominous in the extreme. It sounded, quite simply, like a declaration of war.

Putin's strength now looks like his main weakness, with people too loyal - or scared - the challenge him

https://www.cnbc.com/2022/03/31/russias-putin-is-so-powerful-everyone-is-scared-to-tell-him-the-truth.htmlnge him

- Declassified U.S. intelligence suggests Russian President Vladimir Putin feels he was misled by military leaders over the dire invasion of Ukraine.

- There are major question marks over whether Putin's inner circle feels able to question his rationale or strategy when it comes to Russia's invasion.

President Vladimir Putin's immense power looks like it might now be a key weakness for the Russian leader, with those around him seemingly too scared to tell him the truth, or to question his rationale or strategy when it comes to Russia's invasion of Ukraine.

"Putin systematically got rid of people who could have challenged him, leaving only the most loyal and fearful ones," Anton Barbashin, a Russian political analyst and editorial director of the journal Riddle, told CNBC on Thursday.

"Any autocrat or dictator, the longer he stays in power, eventually surrounds himself with people that are first loyal, and only then (even if so) are competent," he added.

"We have a fix for it — it is called the separation of power and office term limits, but Putin believed he could work around it. No one can. So we have both the nations of Ukraine, and to a lesser degree Russia, paying for it."

Newly declassified U.S. intelligence released on Wednesday suggested that Putin has not been given the whole truth about Russia's botched invasion of Ukraine and that the president feels misled by his military leaders who did not tell him key details about the war — which has not gone to plan with Russian forces bogged down in fighting in the north, east and south — because they feared angering him.

Barbashin said that while he was cautious about accepting the veracity of the U.S. intelligence update wholesale, it was likely that the information Putin receives — mostly coming from his security agencies or his own presidential administration — is biased and inaccurate.

Such information, Barbashin noted, "can and most likely is always manipulated by people around him.

"No one wants to deliver bad news and every agency that works for him wants to be the one that proves its value before him," he said. "We don't know what exactly is happening there. But clearly, judging by some noise ... Putin is not happy with how war is going."

CNBC has contacted the Kremlin for a response to the intelligence report and is awaiting a response.

Analysts say it's not just military commanders who are scared of Putin, and that it's a pervasive problem throughout Russian government circles, from the heights of Putin's inner circle to highly qualified civil servants who are scared to question the regime or the war in Ukraine.

"They're very much afraid — very much afraid," Vladimir Milov, a Russian opposition politician and former deputy energy minister, who now lives in Lithuania, told CNBC on Wednesday.

"Believe me, I have a lot of sources in the Russian government and nobody is actually supporting the war — maybe save for a few people in Putin's inner circle — nobody is supporting what Putin is doing."

"I would say that among government circles, support for what Putin is doing is near zero," he added.

When asked why many civil servants don't just quit their posts, Milov said most feel trapped and scared of the consequences.

"They have nowhere else to go. They will not be accepted in the West after essentially assisting Putin to launch the war, so most of them are really trapped and feel like they have no choice but to sit and wait."

Milov added that Russian government personnel have been "persecuted" to a larger extent than even opposition figures lately.

"Not a single day has passed where some deputy minister or some deputy governor [has not been] raided or arrested or so on. They're under 24/7 FSB security service surveillance, all of them, if they make one wrong move it's immediately reported and they could face, basically, jail time."

As the war in Ukraine enters its sixth week on Thursday, there is little sign of the invasion coming to a swift conclusion and every indication it is becoming a war of attrition, with each side trying to wear the other down.

Putin is widely believed to have expected Russian forces to easily occupy the country with the aim of unseating the Ukrainian government and installing a pro-Russian regime as Moscow looks to expand its sphere of influence over former Soviet states.

Defense analysts have said that Russian troops were ill-prepared for the invasion but this may not have been communicated to Putin by military commanders eager to please, and reluctant to look incompetent — or indeed for the forces under their command to look incapable.

"We've seen Russian soldiers — short of weapons and morale — refusing to carry out orders, sabotaging their own equipment and even accidentally shooting down their own aircraft," Jeremy Fleming, the head of the U.K.'s cyber-intelligence agency GCHQ, said in a speech Thursday, stating that Putin "overestimated the abilities of his military to secure a rapid victory."

"And even though we believe Putin's advisors are afraid to tell him the truth, what's going on and the extent of these misjudgments must be crystal clear to the regime," he added.

No speaking truth to power

Experts are asking whether the invasion of Ukraine — which has had unintended consequences for Russia — could backfire spectacularly on Putin, leaving him vulnerable to an uprising at home, as living standards fall, or a coup led from within by members of his political and business elite.

Analysts note that there appears to be very little pressure on Putin to bring the war to an end, with little evidence that any members of Russia's political or business elite were mobilizing against the Ukraine war.

"Certainly Russia has suffered higher casualties than it expected ... and certainly sanctions are more significant than Russia was counting on, but at the end of the day the Kremlin is insulated from much domestic political pressure," Christopher Miller, assistant professor of international history at the Fletcher School of Law and Diplomacy at Tufts University, told CNBC on Wednesday.

Whether these misjudgments have made him more vulnerable to a potential overthrow or coup is uncertain, however.

Putin is widely seen to have derived his power from protecting and enriching a business elite, as well as persecuting Russia's political opposition, among whom the most prominent figure is Alexei Navalny who was imprisoned on what are widely seen as trumped-up charges.

Putin is also said to be surrounded by "siloviki," or "strongmen," who were former colleagues of his in the KGB (the predecessor of the FSB, Russia's security service) or who come from the military and security services such as the GRU (the foreign military intelligence agency) or the FSO — the Federal Protective Service, a federal government agency believed to have around 50,000 personnel who are responsible for protecting high-ranking state officials, of course including the president.

As such, Putin is seen as having a cocoon of protection around him, making him virtually untouchable.

Since the war started in Ukraine in February, there has been talk of the "nuclear triad" in the media. According to Britannica Academic, "both the United States and Russia have had the strongest and longest-living triads."

A nuclear triad is a military structure that includes land-launched atomic missiles, submarines armed with nukes, and aircraft armed with nuclear missiles and bombs. This approach helps to ensure the opponent cannot easily destroy all of a nation's nuclear weapons in one attack.

Recently, as part of the analysis of the possible sabotage of the Nord Stream, one of Russia's submarines with nuclear weapons was mentioned: the K-329 Belgorod. (Pictured here at the top.)

Combined with the anechoic coverings with which the K-329 Belgorod is equipped, which allows it to create an acoustic screen, making it difficult to detect, the Belgorod is one terrifying weapon.

Codenamed "Status-6", the Poseidon is a 78 feet long (24 meters), nuclear-powered crewless submarine vehicle equipped with two-megaton Cobalt-60 nuclear warheads.

If detonated near a coast, this nuclear torpedo would cause a "radioactive tsunami," with waves up to 1640 feet (500 meters) high, which would also inflict damage inland and, according to simulations by Russian state TV, would demolish entire countries, such as the UK.

But the Belgorod is not the only Russian weapon that keeps the West on high alert: to keep it company, there are intercontinental ballistic missiles, including the Sarmat.

The Sarmat is considered the flagship of the new Russian military programs. According to Al Jazeera, Putin once declared it a weapon that "has no equal" in the world and is "capable of evading any missile defense system." All while carrying 15 nuclear warheads along a flight path up to 11,184 miles (18,000 kilometers).

Whether or not Russia will resort to a nuclear weapons or it is only a threat remains to be seen. For example, newspapers such as the New York Times recognize the war potential of the tactical nuclear weapons available to Moscow.

One must also consider another element: the high long-term cost that could discourage the use of such weapons. In addition, such a drastic measure would surely result in a loss of the few allies Putin has left.

Other newspapers, such as The Guardian, have questioned which target Moscow might try to hit. One of the hypotheses that most convince analysts is that if Putin decided to use nuclear arms, it would be with a tactical nuclear weapon limited to the Ukrainian territory, towards a strategic base, or a specific unit of the Ukrainian army.

In this case, NATO, in theory, could not intervene directly to defend Ukraine by attacking Russian territory. Nor could NATO intervene by using either conventional or nuclear weapons since, despite Zelensky's repeated requests, Ukraine is not a part of the Alliance. If NATO intervened, then the scale of the conflict would most likely become global.

In the aftermath of the referendum on the annexation of the four Ukrainian territories to Russia, in a press conference, Jens Stoltenberg (pictured), NATO secretary, clarified the Alliance's position regarding "nuclear blackmail." Stoltenberg called the Russian leader's "nuclear rhetoric" dangerous, warning that "NATO is vigilant, monitors what Russia's military forces do."

The national security advisor of the United States, Jake Sullivan, made the country's stanceHere’s what Beijing has added to its military might this past year

China has undergone a major expansion of its nuclear arsenal according to new reports and the numbers far exceed past projections. Here’s what we know about China’s latest nuclear capabilities and what that means for the world. on Putin's nuclear threats clear during a press conference at the White House on September 30, 2022. Sullivan told reporters that the United States was taking the risk very seriously and communicating directly with Russia about the issue, including about decisive responses the United States would take if Moscow went down "that dark road."

Russia's nukes and why Putin scares world leaders so much (msn.com)

The Daily Digest, China has seriously expanded its nuclear arsenal and that's worrying, Story by Zeleb.e

The Daily Digest

China has seriously expanded its nuclear arsenal and that's worrying (msn.com)

https://ChChina’s success

A key to China’s future success will be its “new fast breeder reactors and reprocessing facilities” the report commented, which it noted will be used to “produce plutonium for its nuclear weapons program” despite China saying the tech is used for peaceful purposes. ina’s success

A key to China’s future success will be its “new fast breeder reactors and reprocessing facilities” the report commented, which it noted will be used to “produce plutonium for its nuclear weapons program” despite China saying the tech is used for peaceful purposes. www.msn.com/en-ie/

images/PutinScaresWorldLeadersP30.png

China has undergone a major expansion of its nuclear arsenal according to new reports and the numbers far exceed past projections. Here’s what we know about China’s latest nuclear capabilities and what that means for the world.

The U.S. Department of Defense believes that China has roughly 500 nuclear warheads in its arsenal as of May 2023 according to the department's annual China Military Power Report. This should be worrying for any government.

China’s Developing a larger nuclear arsenal

China is developing its nuclear arsenal at a scale and complexity that has not been seen in the country before, which includes expanding the amount of land, sea, and air-based delivery platforms China can draw in the future. current nuclear inventory includes one hundred more warheads than it did in the previous year, a statistic that shows the country’s ability to rapidly assemble advanced nuclear weaponry on par with other leading states.

images/PutinScaresWorldLeadersP33.png

The Department of Defense noted in its report on China’s military power that Beijing will continue to “rapidly moderDeveloping a larger nuclear arsenal

China is developing its nuclear arsenal at a scale and complexity that has not been seen in the country before, which includes expanding the amount of land, sea, and air-based delivery platforms China can draw in the future. nize, diversify, and expand its nuclear forces” and added that the country’s modernization dwarfs previous efforts.

images/PutinScaresWorldLeadersP34.png

China is developing its nuclear arsenal at a scale and complexity that has not been seen in the country before, which includes expanding the amount of land, sea, and air-based delivery platforms China can draw in the future.

Moreover, investment and construction have also expanded and the report remarked that China will “probably have over 1,000 operational nuclear war China’s readiness level

Many of the new nuclear weapons being added to China’s arsenal will be deployed at a level of readiness that will allow Beijing to continue the growth of its nuclear arsenal and put China on track to complete its modernization. warheads by 2023.”

However, this isn’t the most worrying finding of the report.

images/PutinScaresWorldLeadersP35.png

Many of the new nuclear weapons being added to China’s arsenal will be deployed at a level of readiness that will allow Beijing to continue the growth of its nuclear arsenal and put China on track to complete its modernization.

The Department of Defense estimated that China will reach President Xi Jinping’s goal of becoming a world-class military power by 2049, meaning Beijing would be able to go toe-to-toe with the United States in a possible war.

images/PutinScaresWorldLeadersP38.png

“What they’re doing now, if you compare it to what they were doing about a decade ago, it really far exceeds that in terms of scale and complexity,” an unnamed Department of Defense official told Politico about China’s efforts.

images/PutinScaresWorldLeadersP38.png

“They’re expanding and investing in their land, sea, and air-based nuclear delivery platforms, as well as the infrastructure that’s required to support this quite major expansion of their nuclear forces,” the official added.

A key to China’s future success will be its “new fast breeder reactors and reprocessing facilities” the report commented, which it noted will be used to “produce plutonium for its nuclear weapons program” despite China saying the tech is used for peaceful purposes.

The construction of three new solid-propellent fuel silo fields was completed in 2022 and these fields can house as many as 300 new intercontinental ballistic missile silos, which will give the country a greater nuclear readiness.

“This obviously raises a lot of concerns for us,” a senior defense official explained about the Chinese nuclear issue on October 18th. “What we’d really like to see is for them to be more transparent about their nuclear buildup.

CNN noted the defense official added the United States wanted to see “greater interest” on the Chinese side to discuss “strategic stability and risk reduction issues.” However, it is unclear if that will happen in the future.

China has moved toward a far more aggressive international posture in recent years as part of the country’s mission to revamp the Chinese image on the world stage and turn China into one of the world’s leading powers.

Military expansion in China isn’t limited to its nuclear arsenal according to the report by the Department of Defense, which wrote that Beijing has also expanded the country’s submarine and surface ships assets by 30 vessels.

China has seriously expanded its nuclear arsenal and that's worrying (msn.com)

China has seriously expanded its nuclear arsenal and that's worrying (msn.com)

China’s defense budget was also increased by 7.1% which may help Beijing bridge its current military gaps. At present, China is far behind the U.S. and Russia in its nuclear capacity with America’s arsenal sitting at 5224 and Russia’s at 5,880, Politico reported.

Putin’s closest media ally warns about coming world war, Story by Zeleb.es •

The Daily Digest

Putin’s closest media ally warns about coming world war (msn.com)

One of Vladimir Putin’s closest allies in Russian media warned of a coming world war he claims will be fought between the West and Muslim nations supported by Russian arms and weapons. Here’s what was said and why it matters.

Vladimir Solovyov is believed to be one of the “most influential propagandists in Russia” according to Politico and has been the host of the popular television show “Evening with Vladimir Solovyov” on the Russia-1 channel since 2012.

The U.S. The State Department reported Solovyov was once a fierce critic of the Kremlin but has become one the greatest uncritical supporters of President Putin and often uses his platform to spread both propaganda and disinformation.

With that in mind, it would make sense that during one of Solovyov’s latest episodes, he spent time railing against the U.S. for sending Army Tactical Missile Systems (ATACMS) to Ukraine, calling on Russia to supply America’s enemies.

Solovyov’s remarks were translated on YouTube by Russian Media Monitor, which is an independent project dedicated to monitoring Russian media and propaganda, and were reported on by Newsweek. Here’s what Solovyov said.

"They delivered ATACMS. We should deliver everything America's enemies need," the Russian media figure remarked. "To all of them! Any weapons that they need!” Solovyov continued before adding in his distinct theatrical flare.

"To make sure there is not one spot on this Earth where soil doesn't burn under the feet of these neo-colonialist critters,” Solovyov said. It may sound hyperbolic but Solovyov's commentary is typical of what can be heard on his show.

The Russian propagandists went on to say that if the United States was supplying arms to Russia’s enemies to kill Russian people then the government would be providing weapons to North Korea, Syria, and anyone else that wanted them.

Soloyvov said that Russia should give America’s enemies “everything” so that not one American soldier would feel safe while on foreign territory. Then he went on to declare to his audience that a new world war was coming.

"Do you even understand what will happen if a global jihad will start?" Solovyov stated, with Newsweek reporting that he went on to claim that nobody could grasp the reality of what could happen if a religious war were called, all of which would be the West’s fault.

Solovyov made his comments in the immediate aftermath of the bombing at the al-Ahli Hospital in Gaza City, and his remarks were a good example of how the presenter uses world events to shape a Russian narrative that fits within the Kremlin’s messaging.

However, there is a real possibility the conflict unfolding in the Middle East could result in a large regional war, something that the former Russian President and current Deputy Chairman of the Russian Security Council Dmitry Medvedev commented on.

“The Middle East is seeing another war. A cruel war without rules. A war based on terror and the doctrine of disproportionate use of force against the civilian population. As it is said today, both sides have gone 'berserk,'" Medvedev told Russia’s Izvestia.