Has Russia Sent Warships To Israel In Support Of Palestine

HasRussiaSentWarshipsToIsraelInSupportOfPalestine

-

Handy Easy Email and World News Links WebMail

GoogleSearch INLTV.co.uk YahooMail HotMail GMail - news.sky.com/watch-live New York Post nypost.com YouTube

- Well Funded Private Group Supported by Donald Trump and other Millionaires and Billionaires Are Preparing A Private Prosecution Against USA President Joe Biden, USA Secretary Antony Blinken and Israeli Prime Minister Benjamin for Various War Crimes Which Includes Conspiracy to Murder and injure over 70,000 innocent Palestinian Women and Children in Gaza and Westbank In Palestine

"International law has collapsed... If Israel were in the Palestinians' position, the world would not stand still and would act," said Ramzy Aidy, a Gaza resident with a doctorate in law.

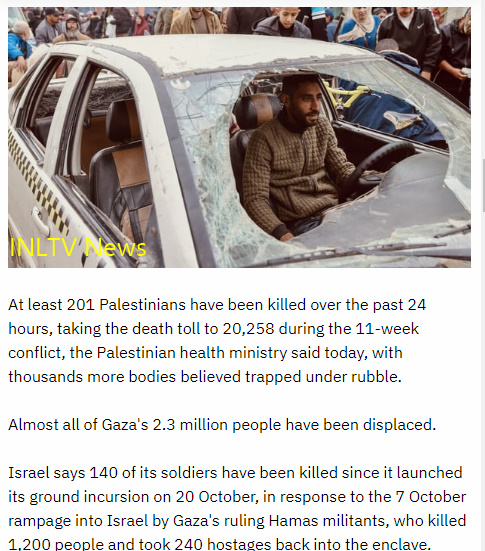

At least 201 Palestinians have been killed over the past 24 hours, taking the death toll to 20,258 during the 11-week conflict, the Palestinian health ministry said today, with thousands more bodies believed trapped under rubble.

Almost all of Gaza's 2.3 million people have been displaced.

An online argument between Stavridis and the Russian news media outlet Sputnik was triggered when Sputnik published a post on Twitter quoting top officials associated with the alliance allegedly recognizing Russia’s military strength.

Former NATO Commander reminds Russia of his stark prediction (msn.com)

Former NATO Commander reminds Russia of his stark prediction (msn.com)

The quotes of each leader appeared to cast Russia in a positive light with Sotltenberg’s comments focused on the tough defenses Moscow prepared against Ukraine's offensive while Von Sandrart’s quote noted Russia’s desire to win the conflict.

Former NATO Commander reminds Russia of his stark prediction (msn.com)

“Putin’s economy is growing … and his armies … have stiffened into capable defenders behind their belts of mines, barriers, and tanks, all protected by air power Ukraine cannot match,” read the quote from Stavridis posted by Sputnik.

Former NATO Commander reminds Russia of his stark prediction (msn.com)

The retired American admiral and former NATO commander didn’t take too kindly to the post Sputnik published and responded to the Russian news outlet, informing its readers that the media agency that it forgot to publish another key quote.

Former NATO Commander reminds Russia of his stark prediction (msn.com)

Stavridis wrote: “You failed to remind your followers I've also said this year that: Putin murdered Prigozhin, that Putin is the greatest salesman for NATO membership ever, and that he thinks he is Stalin but will end up like Nicholas II, the last Tsar of Russia.”

Former NATO Commander reminds Russia of his stark prediction (msn.com)

While it may not seem like much, the last part of the retired admiral's message is a very important statement since Nicholas II was overthrown and abducted during the Russian Revolution. He was ultimately murdered along with his entire family in 1918.

Former NATO Commander reminds Russia of his stark prediction (msn.com)

Stavridis predicted that Putin would face the same fate as Nicholas II in February 2023 while discussing the casualty rate Russia was suffering along the frontlines of the war at that time, specifically around the cities of Bakhmut and Vuhledar.

Former NATO Commander reminds Russia of his stark prediction (msn.com)

“He thinks he's Stalin conducting World War II. He's going to end up like Nicholas II, the last tsar of the Russians, because he is running out of these troops,” Stavridis explained to MSNBC’s Ali Veshi according to a video clip of the conversation.

Former NATO Commander reminds Russia of his stark prediction (msn.com)

Newsweek spoke with Stavridis via an email about his most recent comments online and the retired admiral provided more context on the serious situation he believes Putin will face as the war against Ukraine continues.

Former NATO Commander reminds Russia of his stark prediction (msn.com)

"Putin continues to hold unitary power in Russia, but certainly the rumblings of discontent are evident—from the Prigozhin rebellion to the hundreds of thousands of young military-age males voting with their feet and departing their native land," Stavridis wrote

Former NATO Commander reminds Russia of his stark prediction (msn.com)

"Over time, I'd say the odds are higher of Putin ending up being overthrown like Nicolas II than they are of him meeting a natural demise like Stalin,” the retired admiral went on to explain before providing the only way Putin could avoid that fate.

Former NATO Commander reminds Russia of his stark prediction (msn.com)

Stavridis told Newsweek that Putin needed to negotiate an end to the conflict in Ukraine that would allow him to declare victory and hold onto the territory he captured as well as the land annexed in the Crimean Peninsula.

Former NATO Commander reminds Russia of his stark prediction (msn.com)

However, Ukrainian officials are unlikely to negotiate any peace that trades the country’s land in exchange for an end to the war. President Volodymyr Zelensky has proposed a ten-point peace plan that includes the restoration of Ukraine's territorial integrity.

Former NATO Commander reminds Russia of his stark prediction (msn.com)

When asked in September during an interview with CBS News if he would trade land for peace, Zelesnky said: “No. This is our territory.” Only time will tell if his words prove true, just as it will reveal if Admiral Stavridis' prediction about Putin was correct

StarsInsider The Korean War: one of the most misunderstood conflicts in history Story by Stars Insider

The Korean War: one of the most misunderstood conflicts in history (msn.com)

Palestinian relatives perform funeral prayer near the dead bodies of their beloved ones

Al Jazeera'

and U.

Iran Russia Attack On US Base Near Is

Fighting Rages On In Gaza As Israel Takes Control Of Northern Gaza

https://www.rte.ie/news/2023/

FightingRagesOnInGazaAsIsraelT

Israel battled Hamas militants in pursuit of its elusive goal of full control of northern Gaza after the UN Security Council appealed for more aid for the Palestinian enclave but stopped short of demanding a ceasefire.

Thick smoke hung over the northern town of Jabalia - which is also home to Gaza's largest refugee camp - and residents reported persistent aerial bombardment and shelling from Israeli tanks, which they said had moved further into the town.

Hamas' armed wing Al Qassam Brigades said it had destroyed five Israeli tanks in the area, killing and injuring their crews, after reusing two undetonated missiles launched earlier by Israel. The report could not be independently verified.

Israel's chief military spokesperson said yesterday that its forces had achieved almost complete operational control of northern Gaza and were preparing to expand the ground offensive to other areas, with a focus on the south.

US President Joe Biden discussed the situation with Israeli Prime Minister Benjamin Netanyahu today, the White House said.

Israel's main ally has kept up its support while expressing concern over the growing casualty toll and humanitarian crisis in Gaza.

Mr Biden declined to detail his conversation with Mr Netanyahu, telling reporters it was a "private conversation".

But, he added: "I did not ask for a ceasefire."

After days of wrangling to avert a threatened US veto, the UN Security Council yesterday passed a resolution urging steps to allow "safe, unhindered, and expanded humanitarian access" to Gaza and "conditions for a sustainable cessation" of fighting.

The resolution was toned down from earlier drafts that called for an immediate end to 11 weeks of war and diluting Israeli control over aid deliveries, clearing the way for the vote in which the United States, Israel's main ally, abstained.

The United States and Israel oppose a ceasefire, contending it would allow the Islamist militant group to regroup and rearm.

The Israeli Defence Forces (IDF) said they had fired decoy shots in the area of Issa in Gaza City that lured dozens of militants from a building that served as a Hamas headquarters in the north of the enclave.

"During the joint operational activity, IDF ground and intelligence troops directed an IAF fighter jet to strike the building, eliminating the terrorists," it said.

The army also released a video it said showed Hamas tunnels in the Issa area. Neither the location or the date could be independently verified.

Israel accuses the militant group of placing tunnels and other military infrastructure among civilians to use them as human shields, something Hamas denies.

Today, residents and Palestinian media reported that Israeli tanks shelled the town of Juhr ad-Deek in central Gaza. There was no immediate word on casualties.

At least 201 Palestinians have been killed over the past 24 hours, taking the death toll to 20,258 during the 11-week conflict, the Palestinian health ministry said today, with thousands more bodies believed trapped under rubble.

Almost all of Gaza's 2.3 million people have been displaced.

Israel says 140 of its soldiers have been killed since it launched its ground incursion on 20 October, in response to the 7 October rampage into Israel by Gaza's ruling Hamas militants, who killed 1,200 people and took 240 hostages back into the enclave.

Hamas said it had lost contact with a group it said was responsible for five of the Israeli hostages due to Israeli bombardment. More than 100 hostages in total are still believed to be in Gaza.

Health officials and Hamas media said an Israeli air strike on a house in Nusseirat refugee camp in central Gaza killed three people including a journalist of Hamas' Aqsa TV channel and two relatives.

The reporter's death brings to at least 69 the number of journalists killed in the conflict, according to a tally by the Committee to Protect Journalists.

The Israeli military has expressed regret for civilian deaths and blames Iran-backed Hamas for operating in densely populated areas, arguing that Israel will never be safe until the group is eliminated.

Hamas' Aqsa radio later said Israeli planes had bombed and destroyed the headquarters of Aqsa TV and radio station in Gaza City.

An IDF spokesperson declined to comment on Palestinian reports that Israeli forces had begun a ground offensive near Kerem Shalom, east of the Rafah Crossing into Egypt.

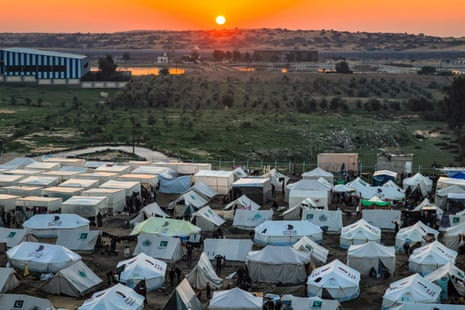

'Where should we go?'

Israel has long urged residents to leave northern areas of Gaza but its forces have also been bombarding targets in central and southern parts of the tiny coastal enclave.

"Where should we go to? There is no place safe," Ziad, a medic and father of six, told Reuters by phone. "They ask people to head to (the central Gaza city of) Deir Al-Balah, where they bomb day and night."

Palestinian mourners attended the burial of a family of four killed in an Israeli airstrike on Khan Younis in southern Gaza.

"International law has collapsed... If Israel were in the Palestinians' position, the world would not stand still and would act," said Ramzy Aidy, a Gaza resident with a doctorate in law.

The conflict has spread beyond Gaza, including into the Red Sea where Yemen's Iran-aligned Houthi forces have been attacking vessels with missiles and drones in retaliation for Israel's assault on the enclave, whose Hamas rulers are backed by Iran.

An Israel-affiliated merchant vessel in the Arabian Sea off India's west coast was struck by an unmanned aerial vehicle, causing a fire, British maritime security firm Ambrey said on Saturday.

An Iranian Revolutionary Guards commander said the Mediterranean Sea could be closed if the United States and its allies continued to commit "crimes" in Gaza, Iranian media reported today, without explaining how that would happen.

The presidents of Iran and Egypt discussed the latest Gaza developments and the prospect of restoring bilateral diplomatic ties in what Iranian state television said was their first phone call. Iran's President Ebrahim Raisi said Tehran would offer all necessary help "to stop the genocide by the Zionist regime".

Israel battled Hamas militants in pursuit of its elusive goal of full control of northern Gaza after the UN Security Council appealed for more aid for the Palestinian enclave but stopped short of demanding a ceasefire. INLTV News

Fighting Rages On In Gaza As Israel Takes Control Of Northern Gaza

Russia maneuvers carefully over the Israel-Hamas war | AP News

Volodymyr Zelensky’s Struggle to Keep Ukraine in the Fight | TIME

Israel Got Suitcases of Cash to Hamas: New York Times Report

Almost 100 journalists killed and 400 imprisoned in 2023, says report

International Federation of Journalists says 68 killed covering Israel-Gaza war, more than in any other conflict in over 30 years

Friends and relatives carry the bodies of the Palestinian journalists Saeed al-Taweel and Mohammed Sobh.

Has Russia Just Sent Warships To Israel In Support Of Palestine

-

Vladimir Vladimirovich Putin

-

An end that is a beginning

Islamic Nations Warning To US Israel After UN Ceasefire Resolution Blocked For Gaza Hamas War

The results of a draft resolution vote are seen on a screen as the UN general assembly holds an emergency special session on the Israel-Hamas war at the UN on 12 December, in New York City.

Israel's Biggest Enemy Isn't Hamas - Shocking Truth Revealed

Israel Using Starvation Of Palesti

Israel Using Starvation Of Palesti

Israel Using Starvation Of Palesti

Israel Using Starvation Of Palesti

Israel Using Starvation Of Palesti

IsraelUsingStarvationOfPalesti

101East Aljazeera INL News Investigates Why A Disproportionately Large Number Of Australian Indigenous Women Disappear In Australia Each Year

Almost 100 journalists killed and 400 imprisoned in 2023, says report

International Federation of Journalists says 68 killed covering Israel-Gaza war, more than in any other conflict in over 30 years

https://www.theguardian.com/media/2023/dec/08/journalists-killed-imprisoned-2023-ifj

A leading organisation representing journalists worldwide has expressed deep concern at the number of media professionals killed around the globe doing their jobs in 2023, with more journalists killed during Israel’s war with Hamas than in any other conflict in more than 30 years.

In its annual count of media worker deaths, the International Federation of Journalists (IFJ) said 94 journalists had been killed so far this year and almost 400 others had been imprisoned.

The figure for deaths is up from 67 in the same period of 2022 – including 12 killed in Ukraine – and double the total of 47 recorded for the whole of 2021.

The group called for better protection for media workers and for their attackers to be held to account.

“The imperative for a new global standard for the protection of journalists and effective international enforcement has never been greater,” said the IFJ president, Dominique Pradalié.

The group said 68 journalists had been killed covering the Israeli-Gaza war since Hamas attacked Israel on 7 October – more than one a day and accounting for 72% of all media deaths worldwide this year. It said the overwhelming majority of them were Palestinian journalists in the Gaza Strip, where Israeli forces continue their offensive.

“The war in Gaza has been more deadly for journalists than any single conflict since the IFJ began recording journalists killed in the line of duty in 1990,” the group said, adding that deaths had come at a scale and pace “without precedent”.

Ukraine also “remains a dangerous country for journalists” almost two years since Russia’s invasion, the organisation said. It said three reporters or media workers had been killed in that war so far this year.

The organisation also deplored media deaths in Afghanistan, the Philippines, India, China and Bangladesh.

It expressed concern that crimes against media workers were going unpunished and urged governments “to shed full light on these murders and to put in place measures to ensure the safety of journalists”.

It noted a drop in the number of journalists killed in North and South America, from 29 last year to seven so far in 2023. The group said the three Mexicans, one Paraguayan, one Guatemalan, one Colombian and one American were killed while investigating armed groups or the embezzlement of public funds.

In Africa, the organisation referred to “four particularly shocking murders”, two in Cameroon and one each in Sudan and Lesotho, “which have failed to be fully investigated to date”.

In all, 393 media workers were being held in prison so far this year, the group said. The biggest number were jailed in China and Hong Kong – 80 journalists – followed by 54 in Myanmar, 41 in Turkey, 40 in Russia and Russian-occupied Crimea, 35 in Belarus and 23 in Egypt.

Russia Sends Warships Off Coast of Gaza (businessinsider.com)

Russia Sends Warships Off Coast Of Gaza In Response To Israel-Palestine Tensions

Israel Got Suitcases of Cash to Hamas: New York Times Report

Israel Got Suitcases of Cash to Hamas: New York Times Report (businessinsider.com)

- Israel tacitly encouraged Hamas to stay in power, according to the New York Times.

- In some cases, Israeli support was more obvious.

- Israeli security forces would help escort millions in funds into Gaza, helping Hamas, NYT reported.

-

Israeli officials are facing backlash after years of Prime Minister Benjamin "Bibi" Netanyahu quietly allowing Hamas to remain in power.

But reporting in the New York Times has revealed that Netanyahu's government was more hands-on about helping Hamas: they helped a Qatari diplomat bring suitcases of cash into Gaza, indirectly boosting the militant organization, according to the report.

-

The calculus — the Times reported on Sunday, citing Israeli officials, Netanyahu's critics, and the man's own reported statements — was to keep Hamas strong enough to counteract the Palestinian Authority in the West Bank, allowing Netanyahu to avoid a two-state peace solution and keep both sides weak.

Israeli security officials got it wrong; they didn't think Hamas was capable, or even interested, in launching a large attack against the Jewish state.

-

To keep Hamas propped up, Netanyahu's government worked with Qatari to keep the money flowing, the New York Times reported. Israel knew that Qatar was supporting Hamas, but didn't oppose the payments and even lobbied American lawmakers not to sanction Qatar.

In 2018, Netanyahu's administration came up with a plan, according to the New York Times. As part of a peace agreement with Hamas, Qatar would bring millions into Gaza to distribute to Gazan families, the outlet reported.

Israeli security officials would meet with a Qatari diplomat at the border between Israel and Jordan, according to the New York Times report.

They would then drive him past the border crossing and into Gaza, according to the outlet.

-

Though the money was meant for Gazan civilians, Western intelligence determined that Hamas was taking money from the funds to use themselves, the outlet reported.

The propped-up peace lasted until October 7, when Hamas fighters launched a terror attack across the Israeli border. The militants killed about 1,200 people and took dozens more hostage, Israeli officials said.

Israel has since responded with a massive bombing and ground campaign in Gaza. About 17,000 people in Gaza have been killed, according to Hamas-led Gazan health authorities.

Though a short ceasefire allowed a hostage exchange between Hamas and Israel, the fighting has since continued.

Russia maneuvers carefully over the Israel-Hamas war as it seeks to expand its global clout

Russia maneuvers carefully over the Israel-Hamas war | AP News

Russia has issued carefully calibrated criticism of both sides in the war between Israel and Hamas. But the conflict also is giving Moscow bold new opportunities — to advance its role as a global power broker and challenge Western efforts to isolate it over Ukraine.

While Moscow lacks leverage to mediate a settlement in the Middle East, it could try to play on some perceived credibility problems with the West’s response to the crisis.

It also expects the Israel-Hamas war to distract attention from the fighting in Ukraine and erode support for Kyiv.

There are risks for Moscow, however. It could damage its relationship with Israel, which until now has kept it from sending weapons to Ukraine.

Russian President Vladimir Putin has condemned the Oct. 7 attack by Hamas militants on towns in southern Israel. At the same time, he warned Israel against blockading the Gaza Strip, likening it to Nazi Germany’s siege of Leningrad during World War II.

He has cast the war as a failure of U.S. diplomacy, charging that Washington has opted for economic “handouts” to the Palestinians and abandoned efforts to help create a Palestinian state.

Putin declared earlier this month that Moscow could play the role of mediator, thanks to its friendly ties with both Israel and the Palestinians, adding that “no one could suspect us of playing up to one party.”

Despite that claim of even-handedness, a U.N. Security Council resolution that Russia submitted last week condemning violence against civilians made no mention of Hamas. It was rejected by the council.

China was among a few countries that backed the Russian draft, reflecting a shared stance by Moscow and Beijing. Chinese and Russian Middle East envoys met last week to discuss working together to help cool the situation, noting their adherence to a two-state solution for Israel and the Palestinians.

While U.S. President Joe Biden, British Prime Minister Rishi Sunak and other Western leaders visited Israel to show support, Putin waited for nine days before calling Israeli Prime Minister Benjamin Netanyahu, even though they previously had developed warm personal ties. Putin also discussed the war in calls with the leaders of Egypt, Iran, Iraq, Syria and the head of the Palestinian Authority.

Putin offered Netanyahu condolences to the families of Israelis killed by Hamas and emphasized “his strong rejection and condemnation of any actions that victimize the civilian population, including women and children,” according to a Kremlin readout of the call. He also emphasized the need for a “peaceful settlement through political and diplomatic means,” it added. Netanyahu’s office said he told Putin that Israel would not stop until it had eliminated Hamas.

Unlike Putin, who carefully balanced his statements, other Russian officials were more blunt in their criticism of Israeli strikes on Gaza.

Konstantin Kosachev, deputy speaker of the upper house of Russian parliament, said that while Hamas unleashed the war, Israel’s response was “disproportionate” and “inhumane.”

Can Russia, Putin Benefit From the Israel-Hamas War?

Where Does Russia Stand on the Israel-Hamas War?

Moscow may temporarily profit from the West’s focus on the Middle East, but navigating its ties in the region will be tricky.

Abed al-Hafeez Nofal, the Palestinian ambassador to Russia, and exiled Hamas deputy leader Mousa Abu Marzook give a press conference along with other representatives of Palestinian political parties and movements in Moscow on Jan. 17, 2017.

Abed al-Hafeez Nofal, the Palestinian ambassador to Russia, and exiled Hamas deputy leader Mousa Abu Marzook give a press conference along with other representatives of Palestinian political parties and movements in Moscow on Jan. 17, 2017.

As Hamas launched its blitz attack against Israel on Oct. 7, some observers were quick to suspect the Moscow-Tehran axis at work.

Russia, so the argument went, was deliberately and directly fueling conflict in the Holy Land to broaden its battlefield with the West. Others drew direct comparisons between Hamas’s vicious onslaught and Russia’s war against Ukraine. Ukrainian President Volodymyr Zelensky argued that one was “a terrorist organization that attacked Israel” and the other “a terrorist state that attacked Ukraine.” (Many Palestinians have taken issue with this characterization.)

It is true that Moscow has long maintained close relations with Hamas, an Islamist group that controls Gaza and enjoys Iranian backing. The militant movement won Palestinian parliamentary elections in 2006 and took over Gaza during the ensuing Palestinian civil war. Hamas has both political and military wings, and some Western states, such as Australia and New Zealand, have only declared the military wing—the Izz ad-Din al-Qassam Brigades—to be a terrorist organization. Others, such as the United States, have not made this distinction.

The Kremlin, for its part, has never declared either wing of Hamas to be a terrorist group. Rather, eager to carve out a niche in the Middle East peace process, Russian diplomats have tried to unify different Palestinian factions, including Hamas, into a single political force in order to restart the peace process and promote a two-state solution.

Hamas delegations have frequented Moscow, meeting with Foreign Minister Sergey Lavrov and Deputy Foreign Minister Mikhail Bogdanov, who holds the Middle Eastern file at the foreign ministry. Russia consulted with Palestinian factions in Doha, Qatar, and Ramallah, in the West Bank, and hosted talks between them at the Institute of Oriental Studies of the Russian Academy of Sciences in Moscow, which I used to frequent as a visiting scholar. Those talks showed that Hamas is far from a Russian puppet: In one round of negotiations, held in Moscow in February 2019, the group’s leadership refused to sign a final statement brokered by the Russian hosts.

Over the years, some Russian-made weapons—such as anti-tank and shoulder-launched anti-aircraft missiles— have made their way into Gaza, likely via Iran. But so far, there is no clear evidence that Russia supported Hamas in planning or executing its surprise attack on Israel.

But that does not mean that Russia is a nonentity in this latest Israel-Hamas conflict. Since launching its full-scale invasion of Ukraine in February 2022, Moscow has dramatically deepened its cooperation with Iran. In return for Iranian combat drones and other military gear, Russia has stepped up its defense support for Tehran, including—as the United States fears—with assistance for its missile and space-launched vehicle programs. There has been a flurry of Iranian-Russian military engagement, including Russian Defense Minister Sergei Shoigu’s tour of an arms exhibition in Tehran last month.

Once an eager mediator in the dispute over Iran’s nuclear program, Russia has also lost enthusiasm for seeing the Joint Comprehensive Plan of Action restored. After its invasion of Ukraine, Russia ceased to push for meaningful and timely progress in the nuclear talks, creating a de facto shield for Iran’s near-nuclear status.

In Syria, Russia and Iran have found common cause in harassing U.S. forces stationed in the northeast. Those troops—numbering about 900 at any given time—remain in Syria to prevent a resurgence of the Islamic State, support U.S.-backed Kurdish forces, and thwart Iranian and Russian ambitions in the country. According to classified documents leaked earlier this year, Russia, Iran, and Syria have established a “coordination center” to direct a concerted effort to drive the U.S. military out.

Russia has taken some steps to compensate for Iran’s empowerment, eagerly supporting normalization between Syria and several Arab states. On balance, however, Russia is enabling rather than constraining Tehran in the region. Even though there is no evidence to support the idea that Iran was intimately involved in planning Hamas’s attack, it has long provided logistical and military support to the militant movement, as well as to other proxy groups in its increasingly decentralized “

A new war in the Middle East suits Russian President Vladimir Putin. Moscow hopes to deflect Western attention and resources away from Ukraine by cultivating global pressure points and distractions.

In walking away from the Black Sea Grain Initiative (which had ensured the wartime export of Ukrainian grain) in July, Russia has caused disruptions to global grain supplies, creating concern around the globe and especially among African states. Moscow is also regularly stoking fears of nuclear escalation over the war in Ukraine, most recently insinuating that it might de-ratify the multilateral Comprehensive Nuclear Test Ban Treaty. Lamenting that the United States (among a few other countries, such as China, Iran, and Israel) never ratified the treaty, Russia has signaled its desire to establish parity with Washington.

Renewed instability in the Middle East would likely distract Western states, chiefly the United States, from NATO’s eastern flank and could impose resource constraints on the provision of arms and ammunition to Ukraine. Should Israel-Saudi normalization—which Washington has worked toward tirelessly over recent months—become a casualty of the latest Israel-Hamas war, Moscow would score an additional win. Russia has regarded all regional diplomacy arising from the Abraham Accords as a U.S. project that sidelines Russia.

While Russia could extract benefits from an uptick in violence between Israel and Hamas, there is no evidence that it did play a role in directly instigating Hamas’s actions. Israel has not provided Kyiv with lethal weapons, reluctant to antagonize Russia—and Putin would like to keep it that way. Despite experiencing rough patches over the past year and a half, especially under Israeli Prime Minister Yair Lapid (who was in office briefly from July to December 2022), Russian-Israeli relations remain rich and robust. The two countries trade, coordinate their air forces’ activities in Syria, and enjoy extensive diaspora ties. Current Israeli Prime Minister Benjamin Netanyahu and Putin have personal chemistry. Directly aiding and abetting Hamas’s vicious attack would threaten to undo all that.

Russia also needs to be careful what it wishes for. While it might temporarily profit from a renewed Western focus on the Middle East and the scuttling of Arab-Israeli normalization, Moscow most likely does not want to see Iran and Israel drift into full-scale war. Broader conflict would surely engulf not just Lebanon but also Syria, where Russian-controlled air and naval bases underpin Moscow’s power projection into the Eastern Mediterranean and Africa. With most of its active-duty military and hardware committed to Ukraine, Russia would not have the bandwidth to get involved in a bigger Middle Eastern conflagration.

Most importantly, Russia still values its ties with Israel and the Arab states, notwithstanding its growing alignment with Iran. Since Oct. 7, Moscow has been keen to pose as peace broker while blaming this latest Middle Eastern war on past mistakes made by the West. In an act of diplomatic showmanship, Russian officials have also busily liaised with and hosted Arab counterparts. Russia also presented a draft resolution on the war in the U.N. Security Council earlier this week. Backed by Palestine as well as several Arab and non-Western states, the text—which did not mention Hamas by name—failed to elicit majority support.

Russia has maneuvered itself into a difficult balancing act. It took Putin nearly 10 days to call Netanyahu to express condolences for the Oct. 7 attack. Russia has refrained from referring to the massacre as terrorism, breaking with past precedent, and Russian media coverage of the unfolding war has adopted a clear pro-Palestinian slant. By emphasizing the suffering of Palestinian civilians and distancing itself from Washington’s unequivocal support for Israel, Moscow is tapping into powerful grievances about Palestine across the Middle East and global south. Here, the Kremlin hopes for backing in its broader confrontation with the West.

Yet, for all its catering to pro-Palestinian sentiments, Russia does not want a break with Israel. And for all its professed common cause with Iran in challenging U.S. primacy, Russia does not seek to go all in with Tehran, either. Russian diplomacy under Putin has always tried—and continues to try—to balance between mutually antagonistic players in the Middle East, since this maximizes Russian gains. Navigating small fires, rather than a big regional war, while dealing with all sides is the playbook that suits Moscow best.

But Putin won’t be the one to set the future course of events. The United States has sent an aircraft carrier strike group to the Eastern Mediterranean and vowed unequivocal support for Israel. Should the fighting escalate and expand, with Washington coming down hard on Israel’s side, Russia would likely drift yet further into Iran’s orbit given the broader geopolitical backdrop of this new Middle Eastern war.

My FP: Follow topics and authors to get straight to what you like. Exclusively for FP subscribers. Subscribe Now | Log In

Hanna Notte is the director of the Eurasia Nonproliferation Program at the James Martin Center for Nonproliferation Studies and a nonresident senior associate with the Europe, Russia, and Eurasia Program at the Center for Strategic and International Studies. Twitter: @HannaNotte

What Will Russia Do With Gaza Chaos?

What Putin Stands to Gain From Israel-Hamas War

In walking away from the Black Sea Grain Initiative (which had ensured the wartime export of Ukrainian grain) in July, Russia has caused disruptions to global grain supplies, creating concern around the globe and especially among African states. Moscow is also regularly stoking fears of nuclear escalation over the war in Ukraine, most recently insinuating that it might de-ratify the multilateral Comprehensive Nuclear Test Ban Treaty. Lamenting that the United States (among a few other countries, such as China, Iran, and Israel) never ratified the treaty, Russia has signaled its desire to establish parity with Washington.

Renewed instability in the Middle East would likely distract Western states, chiefly the United States, from NATO’s eastern flank and could impose resource constraints on the provision of arms and ammunition to Ukraine. Should Israel-Saudi normalization—which Washington has worked toward tirelessly over recent months—become a casualty of the latest Israel-Hamas war, Moscow would score an additional win. Russia has regarded all regional diplomacy arising from the Abraham Accords as a U.S. project that sidelines Russia.

U.S. Defense Secretary Visits Israel to Push Transition Into New Phase of War

The Biden administration wants Israel to pivot to a less intense phase of the war as soon as possible.

The results of a draft resolution vote are seen on a screen as the UN general assembly holds an emergency special session on the Israel-Hamas war at the UN on 12 December, in New York City.

ttps://www.theguardian.com/world/2023/dec/18/un-security-council-vote

The United Nations security council has postponed a vote calling for a sustainable cessation of hostilities in Gaza to give more time for diplomats to meet US objections to the wording of the draft resolution.

The vote had been due on Monday in New York but the US said it could not support a reference to a “cessation of hostilities”, but might accept a call for a “suspension of hostilities”.

Here are some of the latest images coming out of Gaza, as the fighting continues.

The Atrocities In Gaza Are The Perfect Embodiment Of ‘Western Values’

|

In Israel-Hamas war, Russia's leverage erodes, outflanked by US naval power - Al-Monitor: Independent, trusted coverage of the Middle East

Russia, historically viewed as a major stakeholder and player in the Middle East since the Cold War, is seeing its leverage eroding as the Hamas-Israel war enters its third week, and the Kremlin is absent despite attempts to mediate the conflict.

While Russian pro-government experts relay diplomatic signals from Moscow, they also recognize that Moscow has little real chance of acting as an intermediary, and by way of explanation assert that "neither Israel nor Hamas has a request for mediation." In reality, Russia has long since excluded itself from efforts at an Israeli-Palestinian settlement. Moreover, amid the current buildup of US combat capabilities in the Mediterranean in support of Israel, Moscow, for the first time since sending troops to Syria in 2015, has no means of exercising deterrence in the region.

A pro-Palestinian message?

On Oct. 13, Russian President Vladimir Putin said that Russia could help mediate between Israel and Palestine because the Russian side has "good" and "traditional" relations with both sides, and Moscow could not be suspected of "playing along."

Russia can gain from Middle East turmoil — but it could backfire if the war spirals out of control

The conflict in the Middle East is the perfect crisis for Russia, which is reaping a whole host of political benefits. The confrontation between Israel and Hamas has not only boosted the Kremlin’s hopes of changing the mood around the war in Ukraine, but also strengthened its belief that the Western-centric system of international relations is breaking down.

The full-scale invasion of Ukraine in 2022 put an end to most internal Western disagreements when it came to Russia, uniting countries on both sides of the Atlantic. But the Israel-Hamas war has seen divisions resurface at a state level: while the United States insists Israel has a right to self-defense, there have been bitter disagreements between European countries about what position the European Union should take.

There are also societal divides, with protests by opponents and supporters of Israel taking place regularly from Washington to Stockholm. Even state agencies are not immune to these differing views, with media reports of widespread discontent among U.S. officials with the White House’s pro-Israel stance.

Against this backdrop, the war in Ukraine has slipped down the agenda. The United States has said it will provide help to both Israel and Ukraine. But how long can it really be fully engaged in two major conflicts? Moscow’s hopes that the West will eventually tire of providing open-ended support for Kyiv have never looked so justified.

In addition, Washington’s pro-Israel stance undermines the legitimacy of the West’s broader reasons for supporting Ukraine in the eyes of many in the Global South. The moral argument against Russia’s invasion of Ukraine now looks like empty words, particularly in Middle East nations.

Photos of the ruins in Gaza, reports of thousands of dead children, and the outrage of humanitarian organizations have made a deep impression on people in the developing world. People can argue endlessly about the reasons for the war in Ukraine, or Israel’s operation in Gaza, but for many the conclusion is obvious: the United States was critical of Russia when it killed innocent civilians in Ukraine, and now it is silent when its ally Israel does the same thing in Gaza.

A vision of the world in which morals and ideologies are irrelevant—and the only thing that counts are state interests—has long been the dominant one in the Kremlin. And this logic dictates that there is no better outcome for Moscow than the continuation of the Middle East conflict, which is destroying the West’s strategy toward Russia. Moscow does not even have to lift a finger: Israel’s ground operation in Gaza looks unlikely to end anytime soon. When it does, intractable issues will remain.

True, the escalation in Gaza is not without risks for Russia, and if pro-Iranian forces get sucked in, it could become a major headache for the Kremlin. Moscow’s ties with Iran mean it has been drifting toward a pro-Tehran position in the Middle East for the last couple of years, but that does not mean it is ready to support Iran in a war with Israel. Such a development would oblige Russia to pick a side, and would have consequences for Russia’s intervention in Syria.

For now, however, a broader military conflagration in the Middle East looks unlikely. Iran and its proxies have stayed out of the Gaza conflict so far, which means they are less likely to intervene further down the line.

The Israel-Hamas war also poses some domestic dilemmas for the Kremlin. Judging by statements from officials, October’s anti-Semitic pogrom in Dagestan sent shockwaves through the Russian leadership. Nationalism and Russia’s ethnic republics are issues that previously worried the Kremlin. Now, Middle East policy will need to be made with half an eye on public opinion.

At the same time, minimizing these risks should be straightforward. It would be enough to tone down the anti-Israel rhetoric while maintaining some moderate criticism of the country’s actions. Indeed, the pogrom in Dagestan likely convinced the Kremlin that it’s less dangerous to remain on the sidelines in the Israel-Hamas war than to take an active role.

Finally, events in the Middle East have helped the Kremlin convince itself that Russia’s foreign policy in recent years has been the right one.

A charismatic leader should be able to make those around him believe that he is lucky, and that success comes naturally. Whatever the difficulties, President Vladimir Putin apparently believes that every cloud has a silver lining—and he communicates this confidence to his subordinates. Any successes, particularly if they seem to come from nowhere, strengthen both Putin’s fatalism and belief in Putin’s infallibility. Everything is in God’s hands, and God, of course, is on the side of Russia.

There are also more rational arguments. Moscow’s bet on the disintegration of a Western-oriented international order appears to be paying off. Today it’s Israel and Palestine; tomorrow, it could be Taiwan and China. As such, the Middle East conflict confirms the hypothesis that Russia cannot be isolated. The Global South no longer trusts the West, and that means new opportunities for Moscow.

The conflict also shores up the Kremlin’s hope that the difficulties caused by the war in Ukraine will—with time—dissipate on their own. This approach has been tried and tested by Russia many times. Even if the invasion did not go as planned, the logic runs, everything will resolve itself.

Taken together, all of this means that Russia will remain a passive actor in the Israel-Hamas war. Moscow had no role in triggering the crisis, and couldn’t resolve it even if it wanted to. Russia cannot even play the role of an intermediary, because Israel is nervous of its closeness to Tehran. The only option left is to watch events unfold from a distance and repeat empty phrases about a two-state solution. In the meantime, the benefits the Kremlin is reaping from events in the Middle East only serve to convince the Russian elite that they have chosen the right path.

Carnegie does not take institutional positions on public policy issues; the views represented herein are those of the author(s) and do not necessarily reflect the views of Carnegie, its staff, or its trustees.

How the Hamas-Israel Conflict Benefits Russia | TIME

Israeli President Benjamin Netanyahu used to call Russia’s president, Vladimir Putin, his “dear friend.” Since 2015, the Israeli leader has visited Russia more than 10 times, and proudly hung a giant poster of the two presidents shaking hands over his party headquarters during an election campaign in 2019. But the relationship between Russia and Israel has cooled following Russia’s full-scale invasion of Ukraine, even if Israel has remained more reluctant to support Ukraine than its Western allies would have liked.

Even so, it came as a shock to many in Israel to see a group of high-ranking Hamas members meeting with a senior Russian official on Oct. 26. The Israeli Foreign Ministry slammed the decision to invite Hamas members to Moscow as “an act in support of terrorism” and called for Russia to expel the Hamas delegation.

Tense relationships between Russia and Israel have only become more frayed following a riot in Dagestan, in southern Russia, on Oct. 29. Hundreds of rioters stormed an airport to search for Israelis arriving on a flight from Tel Aviv. Israel has condemned the mob and asked Moscow to protect Israeli citizens and Jews in Russia.

In the wake of Hamas’s attacks on Oct. 7, which killed over 1,400 Israelis, experts say Russian officials have tried to toe a difficult line. While Russia has been quick to criticize Israel’s strikes on Gaza, it remains reluctant to sever ties with Israel altogether. As the Israel-Hamas conflict shows little sign of slowing down, Russia may also be hoping that support for Ukraine will be placed on the back burner for the U.S. and its allies.

Here’s what to know about Russia’s relationship with Hamas, and what experts say Russia stands to gain from the rising tensions in the Middle East.

Russia’s Strategic Moves in the Aftermath of Hamas’s Attack

Russia has defended its decision to host Hamas members in Moscow, saying it is important to maintain ties with both sides in the Israel-Hamas conflict. The Russian Foreign Ministry said in a statement that the meetings were part of Russia’s efforts to secure the release of hostages from Gaza.

But Hamas’s description of the meetings paints a different picture. The group praised Russia’s efforts to end what it called “the crimes of Israel that are supported by the West,” according to Russia’s state-owned RIA news agency. In the wake of the meetings, Hamas has announced that it is looking for eight hostages in Gaza that Russia has asked to be released, “because we look at Russia as our closest friend,” Hamas Politburo member Abu Marzouk said on Oct. 28.

Hamas’s visit to Moscow adds to Israeli fears that Russia is readjusting its foreign policy to move closer to Hamas. Palestinian militants have reportedly gotten around Western sanctions by funneling millions through Russian cryptocurrency exchanges. Ukraine’s Head of Defense Intelligence Kyrylo Budanov has also said that Russia has recently supplied Hamas with arms, although he did not provide evidence for his claim. There is no evidence that Russia was involved in instigating Hamas’s Oct. 7 attacks or supplied weapons used.

But Russia has notably not condemned Hamas’s attacks on Oct. 7 as terrorism. Instead, Russian officials have called for both sides to put down arms and reaffirmed its support for a Palestinian state. At the United Nations Security Council, a Russian resolution that called for a ceasefire and the release of all hostages was voted down as it failed to condemn Hamas.

In speeches and public appearances, Russian officials have repeatedly criticized Israel’s treatment of Palestinians. Russian Foreign Minister Sergei Lavrov said on Oct. 28 that Israel’s bombardment of Gaza is against international law. Putin compared Israel’s blockade of Gaza to Nazi Germany’s siege of Leningrad during World War II, one of the most traumatic events in Russian history during which hundreds of thousands of Russian civilians died.

Others in Russia have gone further, arguing that it is time for Russia to reassess its relationship with Israel. “Whose ally is Israel? The United States of America,” Andrei Gurulev, State Duma deputy and member of its Defense Committee, wrote on Telegram. “Whose ally is Iran and its surrounding Muslim world? Ours.”

People wait in line to enter the Israeli Embassy in Moscow to pay tribute after Hamas attacked Israel on October 7.

In the court of public opinion, “Russia has taken a pro-Palestinian position to an extent that even I was surprised by it,” says Hanna Notte, an expert in Russia’s foreign policy in the Middle East at the James Martin Center for Nonproliferation Studies.

“They’re trying to align themselves with the Arab mainstream” as a bid to improve Russia’s standing in the region, says Mark Katz, a professor at George Mason University..

For Hamidreza Azizi, an expert in Iran-Russia relations at the German Institute for International and Security Affairs, Russia’s response to Hamas’s attacks also reflects an inclination towards a closer relationship with Tehran and its allies in the region, which include Hamas. Iran, Israel’s bitter enemy, has become one of Russia's key weapons suppliers for its war in Ukraine.

“I think Russia has made a strategic choice already on who to side with in the Middle East, and it’s not Israel,” says Azizi.

How Russia Stands to Gain from Unrest in the Middle East

So far, Russia may believe that it can profit from the Israel-Hamas conflict, experts say.

While Russian forces remain bogged down in intense fighting along the front in Ukraine, Kremlin propagandists have rejoiced in the hope that the unrest in the Middle East will divert Western support from Ukraine, making it easier for Russia to consolidate its territorial control over parts of Ukraine. “The distraction value from the war in Ukraine is relevant in terms of media attention as well as potentially weapons support over the medium term,” says Notte.

Read More: The Harrowing Work Facing Gaza Doctors in Wartime

The Pentagon has reportedly decided to send Israel tens of thousands of 155mm artillery shells that were originally planned for Ukraine, according to Axios. In addition to artillery ammunition, already in scant supply across Western countries, both Israel and Ukraine need several of the same weapons systems. So far, Pentagon officials have insisted that they will be able to support Ukraine and Israel at the same time. “We can do both, and we will do both,” Defense Secretary Lloyd Austin said at a press conference in Brussels on Oct. 11.

Even so, Russia also faces risks if the conflict spreads beyond Israel and Gaza. Notably, Russia wants to preserve its military presence in Syria without sending in more troops, which would increase pressure on the already hard-pressed Russian forces, analysts say.

If Russia increases its support for Hamas beyond words, it would likely come at the cost of worsening relationships with Israel. Russia has been grateful to Israel for not sending military support to Ukraine, and the two countries maintain contact over military operations in Syria, Katz says.

Even so, Russia has time and time again managed to maintain difficult balancing acts in the Middle East, and may be able to do so once more, winning Arab support without cutting ties with Israel, Notte says.

“I still think that there are more signs that somehow there will still be a sort of modus vivendi between Israel and Russia,” says Notte. “But it also depends on how things play out further down the line in this conflict.”

Read More: Inside Volodymyr Zelensky’s Struggle to Keep Ukraine in the Fight

Read More: What to Know About the Attacks on U.S. Military Bases in the Middle East

The Harrowing Work Facing Gaza Doctors in Wartime

Read More: The Harrowing Work Facing Gaza Doctors in Wartime

The Harrowing Work Facing Gaza Doctors in Wartime | TIME

In Gaza, surgeons are operating by flashlights, rationing anesthetics, and running out of precious fuel needed to keep patients alive.

As the World Health Organization reports that more than one-third of the city’s hospitals are no longer operating and Israel’s bombing continues, health care professionals fear the worst.

“The health system here is in its last throes before it completely boots down. If the electricity goes, that’s it. It just becomes a mass grave,” says Dr. Ghassan Abu-Sittah, a British-Palestinian plastic and reconstructive surgeon who has been working at Al-Shifa hospital over the last two weeks. “There’s no hospital, if there’s no electricity.”

Right now, his sense is that it will be “days, rather than weeks,” until Al-Shifa runs out of fuel needed to keep the hospital running. Palestine’s Ministry of Health said Tuesday that hospital generators will stop running in 48 hours, and aid workers tell TIME that the city is expected to run out of fuel on Wednesday evening.

Read More: ‘Our Death Is Pending.’ Stories of Loss and Grief From Gaza

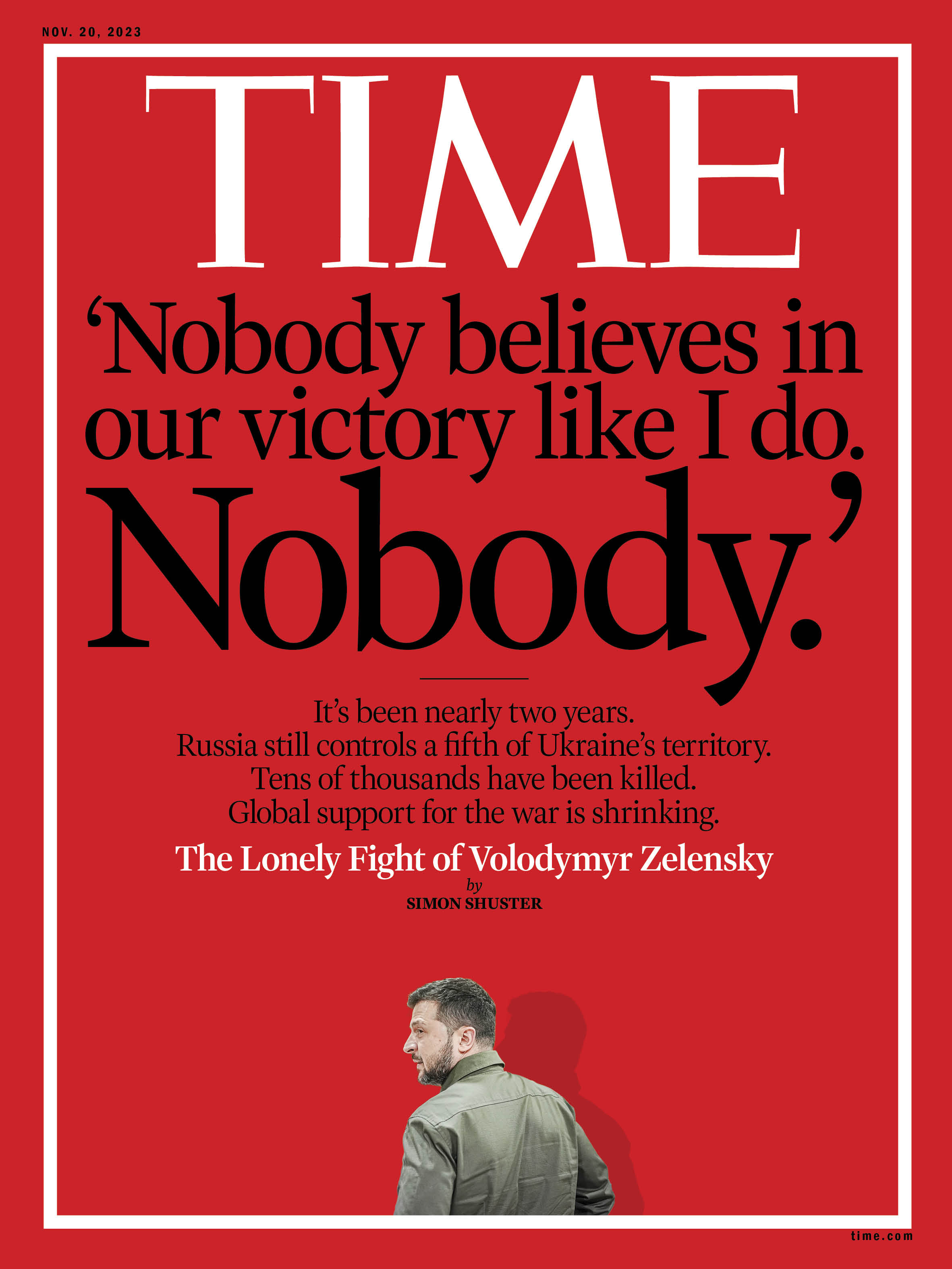

Volodymyr Zelensky’s Struggle to Keep Ukraine in the Fight | TIME

‘Nobody Believes in Our Victory Like I Do.’ Inside Volodymyr Zelensky’s Struggle to Keep Ukraine in the Fight

https://time.com/6329188/

Volodymyr Zelensky was running late.

The invitation to his speech at the National Archives in Washington had gone out to several hundred guests, including congressional leaders and top officials from the Biden Administration. Billed as the main event of his visit in late September, it would give him a chance to inspire U.S. support against Russia with the kind of oratory the world has come to expect from Ukraine’s wartime President. It did not go as planned.

That afternoon, Zelensky’s meetings at the White House and the Pentagon delayed him by more than an hour, and when he finally arrived to begin his speech at 6:41 p.m., he looked distant and agitated. He relied on his wife, First Lady Olena Zelenska, to carry his message of resilience on the stage beside him, while his own delivery felt stilted, as though he wanted to get it over with. At one point, while handing out medals after the speech, he urged the organizer to hurry things along.

The reason, he later said, was the exhaustion he felt that night, not only from the demands of leadership during the war but also the persistent need to convince his allies that, with their help, Ukraine can win. “Nobody believes in our victory like I do. Nobody,” Zelensky told TIME in an interview after his trip. Instilling that belief in his allies, he said, “takes all your power, your energy. You understand? It takes so much of everything.”

It is only getting harder. Twenty months into the war, about a fifth of Ukraine’s territory remains under Russian occupation. Tens of thousands of soldiers and civilians have been killed, and Zelensky can feel during his travels that global interest in the war has slackened. So has the level of international support. “The scariest thing is that part of the world got used to the war in Ukraine,” he says. “Exhaustion with the war rolls along like a wave. You see it in the United States, in Europe. And we see that as soon as they start to get a little tired, it becomes like a show to them: ‘I can’t watch this rerun for the 10th time.’”

After his visit to Washington, TIME followed the President and his team back to Kyiv, hoping to understand how they would react to the signals they had received, especially the insistent calls for Zelensky to fight corruption inside his own government, and the fading enthusiasm for a war with no end in sight. On my first day in Kyiv, I asked one member of his circle how the President was feeling. The response came without a second’s hesitation: “Angry.”

The usual sparkle of his optimism, his sense of humor, his tendency to liven up a meeting in the war room with a bit of banter or a bawdy joke, none of that has survived into the second year of all-out war. “Now he walks in, gets the updates, gives the orders, and walks out,” says one longtime member of his team. Another tells me that, most of all, Zelensky feels betrayed by his Western allies. They have left him without the means to win the war, only the means to survive it.

But his convictions haven’t changed. Despite the recent setbacks on the battlefield, he does not intend to give up fighting or to sue for any kind of peace. On the contrary, his belief in Ukraine’s ultimate victory over Russia has hardened into a form that worries some of his advisers. It is immovable, verging on the messianic. “He deludes himself,” one of his closest aides tells me in frustration. “We’re out of options. We’re not winning. But try telling him that.”

Zelensky’s stubbornness, some of his aides say, has hurt their team’s efforts to come up with a new strategy, a new message. As they have debated the future of the war, one issue has remained taboo: the possibility of negotiating a peace deal with the Russians. Judging by recent surveys, most Ukrainians would reject such a move, especially if it entailed the loss of any occupied territory.

Zelensky remains dead set against even a temporary truce. “For us it would mean leaving this wound open for future generations,” the President tells me. “Maybe it will calm some people down inside our country, and outside, at least those who want to wrap things up at any price. But for me, that’s a problem, because we are left with this explosive force. We only delay its detonation.”

For now, he is intent on winning the war on Ukrainian terms, and he is shifting tactics to achieve that. Aware that the flow of Western arms could dry up over time, the Ukrainians have ramped up production of drones and missiles, which they have used to attack Russian supply routes, command centers, and ammunition depots far behind enemy lines. The Russians have responded with more bombing raids against civilians, more missile strikes against the infrastructure that Ukraine will need to heat homes and keep the lights on through the winter.

Zelensky describes it as a war of wills, and he fears that if the Russians are not stopped in Ukraine, the fighting will spread beyond its borders. “I’ve long lived with this fear,” he says. “A third world war could start in Ukraine, continue in Israel, and move on from there to Asia, and then explode somewhere else.” That was his message in Washington: Help Ukraine stop the war before it spreads, and before it’s too late. He worries his audience has stopped paying attention.

Paramedics help a wounded man after a Russian rocket attack in the eastern Ukrainian city of Kostiantynivka on Sept. 6, 2023.

At the end of last year, during his previous visit to Washington, Zelensky received a hero’s welcome. The White House sent a U.S. Air Force jet to pick him up in eastern Poland a few days before Christmas and, with an escort from a NATO spy plane and an F-15 Eagle fighter, deliver him to Joint Base Andrews outside the U.S. capital. That evening, Zelensky appeared before a joint session of Congress to declare that Ukraine had defeated Russia “in the battle for minds of the world.”

Watching his speech from the balcony, I counted 13 standing ovations before I stopped keeping track. One Senator told me he could not remember a time in his three decades on Capitol Hill when a foreign leader received such an admiring reception. A few right-wing Republicans refused to stand or applaud for Zelensky, but the votes to support him were bipartisan and overwhelming throughout last year.

This time around, the atmosphere had changed. Assistance to Ukraine had become a sticking point in the debate over the federal budget. One of Zelensky’s foreign policy advisers urged him to call off the trip in September, warning that the atmosphere was too fraught. Congressional leaders declined to let Zelensky deliver a public address on Capitol Hill. His aides tried to arrange an in-person appearance for him on Fox News and an interview with Oprah Winfrey. Neither one came through.

Instead, on the morning of Sept. 21, Zelensky met in private with then House Speaker Kevin McCarthy before making his way to the Old Senate Chamber, where lawmakers grilled him behind closed doors. Most of Zelensky’s usual critics stayed silent in the session; Senator Ted Cruz strolled in more than 20 minutes late. The Democrats, for their part, wanted to understand where the war was headed, and how badly Ukraine needed U.S. support. “They asked me straight up: If we don’t give you the aid, what happens?” Zelensky recalls. “What happens is we will lose.”

Zelensky’s performance left a deep impression on some of the lawmakers present. Angus King, an independent Senator from Maine, recalled the Ukrainian leader telling his audience, “You’re giving money. We’re giving our lives.” But it was not enough. Ten days later, Congress passed a bill to temporarily avert a government shutdown. It included no assistance for Ukraine.

Read More: Inside the Race to Arm Ukraine Before Its Counteroffensive

By the time Zelensky returned to Kyiv, the cold of early fall had taken hold, and his aides rushed to prepare for the second winter of the invasion. Russian attacks on Ukrainian infrastructure have damaged power stations and parts of the electricity grid, leaving it potentially unable to meet spikes in demand when the temperature drops. Three of the senior officials in charge of dealing with this problem told me blackouts would likely be more severe this winter, and the public reaction in Ukraine would not be as forgiving. “Last year people blamed the Russians,” one of them says. “This time they’ll blame us for not doing enough to prepare.”

The cold will also make military advances more difficult, locking down the front lines at least until the spring. But Zelensky has refused to accept that. “Freezing the war, to me, means losing it,” he says. Before the winter sets in, his aides warned me to expect major changes in their military strategy and a major shake-up in the President’s team. At least one minister would need to be fired, along with a senior general in charge of the counteroffensive, they said, to ensure accountability for Ukraine’s slow progress at the front. “We’re not moving forward,” says one of Zelensky’s close aides. Some front-line commanders, he continues, have begun refusing orders to advance, even when they came directly from the office of the President. “They just want to sit in the trenches and hold the line,” he says. “But we can’t win a war that way.”

When I raised these claims with a senior military officer, he said that some commanders have little choice in second-guessing orders from the top. At one point in early October, he said, the political leadership in Kyiv demanded an operation to “retake” the city of Horlivka, a strategic outpost in eastern Ukraine that the Russians have held and fiercely defended for nearly a decade. The answer came back in the form of a question: With what? “They don’t have the men or the weapons,” says the officer. “Where are the weapons? Where is the artillery? Where are the new recruits?”

In some branches of the military, the shortage of personnel has become even more dire than the deficit in arms and ammunition. One of Zelensky’s close aides tells me that even if the U.S. and its allies come through with all the weapons they have pledged, “we don’t have the men to use them.”

Ukrainian fighters on the frontlines near Bakhmut on March 17, 2023.Maxim Dondyuk

Since the start of the invasion, Ukraine has refused to release official counts of dead and wounded. But according to U.S. and European estimates, the toll has long surpassed 100,000 on each side of the war. It has eroded the ranks of Ukraine’s armed forces so badly that draft offices have been forced to call up ever older personnel, raising the average age of a soldier in Ukraine to around 43 years. “They’re grown men now, and they aren’t that healthy to begin with,” says the close aide to Zelensky. “This is Ukraine. Not Scandinavia.”

The picture looked different at the outset of the invasion. One branch of the military, known as the Territorial Defense Forces, reported accepting 100,000 new recruits in the first 10 days of all-out war. The mass mobilization was fueled in part by the optimistic predictions of some senior officials that the war would be won in months if not weeks. “Many people thought they could sign up for a quick tour and take part in a heroic victory,” says the second member of the President’s team.

Now recruitment is way down. As conscription efforts have intensified around the country, stories are spreading on social media of draft officers pulling men off trains and buses and sending them to the front. Those with means sometimes bribe their way out of service, often by paying for a medical exemption. Such episodes of corruption within the recruitment system became so widespread by the end of the summer that on Aug. 11 Zelensky fired the heads of the draft offices in every region of the country.

The decision was intended to signal his commitment to fighting graft. But the move backfired, according to the senior military officer, as recruitment nearly ground to a halt without leadership. The fired officials also proved difficult to replace, in part because the reputation of the draft offices had been tainted. “Who wants that job?” the officer asks. “It’s like putting a sign on your back that says: corrupt.”

In recent months, the issue of corruption has strained Zelensky’s relationship with many of his allies. Ahead of his visit to Washington, the White House prepared a list of anti-corruption reforms for the Ukrainians to undertake. One of the aides who traveled with Zelensky to the U.S. told me these proposals targeted the very top of the state hierarchy. “These were not suggestions,” says another presidential adviser. “These were conditions.”

To address the American concerns, Zelensky took some dramatic steps. In early September, he fired his Minister of Defense, Oleksiy Reznikov, a member of his inner circle who had come under scrutiny over corruption in his ministry. Two presidential advisers told me he had not been personally involved in graft. “But he failed to keep order within his ministry,” one says, pointing to the inflated prices the ministry paid for supplies, such as winter coats for soldiers and eggs to keep them fed.

As news of these scandals spread, the President gave strict orders for his staff to avoid the slightest perception of self-enrichment. “Don’t buy anything. Don’t take any vacations. Just sit at your desk, be quiet, and work,” one staffer says in characterizing these directives. Some midlevel officials in the administration complained to me of bureaucratic paralysis and low morale as the scrutiny of their work intensified.

The typical salary in the President’s office, they said, comes to about $1,000 per month, or around $1,500 for more senior officials, far less than they could make in the private sector. “We sleep in rooms that are 2 by 3 meters,” about the size of a prison cell, says Andriy Yermak, the presidential chief of staff, referring to the bunker that Zelensky and a few of his confidants have called home since the start of the invasion. “We’re not out here living the high life,” he tells me in his office. “All day, every day, we are busy fighting this war.”

Amid all the pressure to root out corruption, I assumed, perhaps naively, that officials in Ukraine would think twice before taking a bribe or pocketing state funds. But when I made this point to a top presidential adviser in early October, he asked me to turn off my audio recorder so he could speak more freely. “Simon, you’re mistaken,” he says. “People are stealing like there’s no tomorrow.”

Even the firing of the Defense Minister did not make officials “feel any fear,” he adds, because the purge took too long to materialize. The President was warned in February that corruption had grown rife inside the ministry, but he dithered for more than six months, giving his allies multiple chances to deal with the problems quietly or explain them away. By the time he acted ahead of his U.S. visit, “it was too late,” says another senior presidential adviser. Ukraine’s Western allies were already aware of the scandal by then. Soldiers at the front had begun making off-color jokes about “Reznikov’s eggs,” a new metaphor for corruption. “The reputational damage was done,” says the adviser.

When I asked Zelensky about the problem, he acknowledged its gravity and the threat it poses to Ukraine’s morale and its relationships with foreign partners. Fighting corruption, he assured me, is among his top priorities. He also suggested that some foreign allies have an incentive to exaggerate the problem, because it gives them an excuse to cut off financial support. “It’s not right,” he says, “for them to cover up their failure to help Ukraine by tossing out these accusations.”

U.S. President Joe Biden, right, welcomes Ukrainian President Volodymyr Zelensky at the South Portico of the White House on Sept. 21, 2023.

But some of the accusations have been hard to deny. In August, a Ukrainian news outlet known for investigating graft, Bihus.info, published a damning report about Zelensky’s top adviser on economic and energy policy, Rostyslav Shurma. The report revealed that Shurma, a former executive in the energy industry, has a brother who co-owns two solar-energy companies with power plants in southern Ukraine. Even after the Russians occupied that part of the country, cutting it off from the Ukrainian power grid, the companies continued to receive state payments for producing electricity.

The anticorruption police, an independent agency known in Ukraine as NABU, responded to the publication by opening an embezzlement probe into Shurma and his brother. But Zelensky did not suspend his adviser. Instead, in late September, Shurma joined the President’s delegation to Washington, where I saw him glad-handing senior lawmakers and officials from the Biden Administration.

Soon after he returned to Kyiv, I visited Shurma in his office on the second floor of the presidential headquarters. The atmosphere inside the compound had changed in the 11 months since my last visit. Sandbags had been removed from many windows as new air-defense systems had arrived in Kyiv, including U.S. Patriot missiles, which reduced the risk of a rocket attack on Zelensky’s office. The hallways remained dark, but soldiers no longer patrolled them with assault rifles, and their sleeping mats and other gear had been cleared away. Some of the President’s aides, including Shurma, had gone back to wearing civilian clothes instead of military garb.

When we sat down inside his office, Shurma told me the allegations against him were part of a political attack paid for by one of Zelensky’s domestic enemies. “A piece of sh-t was thrown,” he says, brushing the front of his sweater. “And now we have to explain that we are clean.” It did not seem to trouble him that his brother is a major player in the industry that Shurma oversees. On the contrary, he spent nearly half an hour trying to convince me of the gold rush that renewable energy would see after the war.

Perhaps, I suggested, amid all the concerns about corruption in Ukraine, it would have been wiser for Shurma to step aside while under investigation for embezzlement, or at least sit out Zelensky’s trip to Washington. He responded with a shrug. “If we do that, tomorrow everybody on the team would be targeted,” he says. “Politics is back, and that’s the problem.”

A few minutes later, Shurma’s phone lit up with an urgent message that forced him to cut our interview short. The President had called his senior aides into a meeting in his office. It was normal on Monday mornings for their team to hold a strategy session to plan out the week. But this one would be different. Over the weekend, Palestinian terrorists had massacred many hundreds of civilians in southern Israel, prompting the Israeli government to impose a blockade of the Gaza Strip and declare war against Hamas. Huddled around a conference table, Zelensky and his aides tried to understand what the tragedy would mean for them. “My mind is racing,” one of them told me when he emerged from the meeting that afternoon. “Things are about to start moving very fast.”

From the earliest days of the Russian invasion, Zelensky’s top priority and perhaps his main contribution to the nation’s defense had been to keep attention on Ukraine and to rally the democratic world to its cause. Both tasks would become a lot harder with the outbreak of war in Israel. The focus of Ukraine’s allies in the U.S. and Europe, and of the global media, quickly shifted to the Gaza Strip.

“It’s logical,” Zelensky tells me. “Of course we lose out from the events in the Middle East. People are dying, and the world’s help is needed there to save lives, to save humanity.” Zelensky wanted to help. After the crisis meeting with aides, he asked the Israeli government for permission to visit their country in a show of solidarity. The answer appeared the following week in Israeli media reports: “The time is not right.”

A few days later, President Biden tried to break through the impasse Zelensky had seen on Capitol Hill. Instead of asking Congress to vote on another stand-alone package of Ukraine aid, Biden bundled it with other priorities, including support for Israel and U.S.-Mexico border security. The package would cost $105 billion, with $61 billion of it for Ukraine. “It’s a smart investment,” Biden said, “that’s going to pay dividends for American security for generations.”

But it was also an acknowledgment that, on its own, Ukraine aid no longer stands much of a chance in Washington. When I asked Zelensky about this, he admitted that Biden’s hands appear to be tied by GOP opposition. The White House, he said, remains committed to helping Ukraine. But arguments about shared values no longer have much sway over American politicians or the people who elect them. “Politics is like that,” he tells me with a tired smile. “They weigh their own interests.”

At the start of the Russian invasion, Zelensky’s mission was to maintain the sympathy of humankind. Now his task is more complicated. In his foreign trips and presidential phone calls, he needs to convince world leaders that helping Ukraine is in their own national interests, that it will, as Biden put it, “pay dividends.” Achieving that gets harder as global crises multiply.

But faced with the alternative of freezing the war or losing it, Zelensky sees no option but to press on through the winter and beyond. “I don’t think Ukraine can allow itself to get tired of war,” he says. “Even if someone gets tired on the inside, a lot of us don’t admit it.” The President least of all. —With reporting by Julia Zorthian/New York

MORE MUST-READS FROM TIME

- Taylor Swift Is TIME's 2023 Person of the Year

- Sam Altman on OpenAI and Artificial General Intelligence

- Conversion Therapy Is Still Happening in Almost Every U.S. State

- You’ve Heard of Long COVID. Long Flu Is a Health Risk, Too

- Padma Lakshmi Is Transforming How Americans Think About Food

- Column: The Dangers of Curtailing Free Speech on Campus

- The Most Anticipated Books of 2024

- Want Weekly Recs on What to Watch, Read, and More? Sign Up for Worth Your Time

CONTACT US AT This email address is being protected from spambots. You need JavaScript enabled to view it.

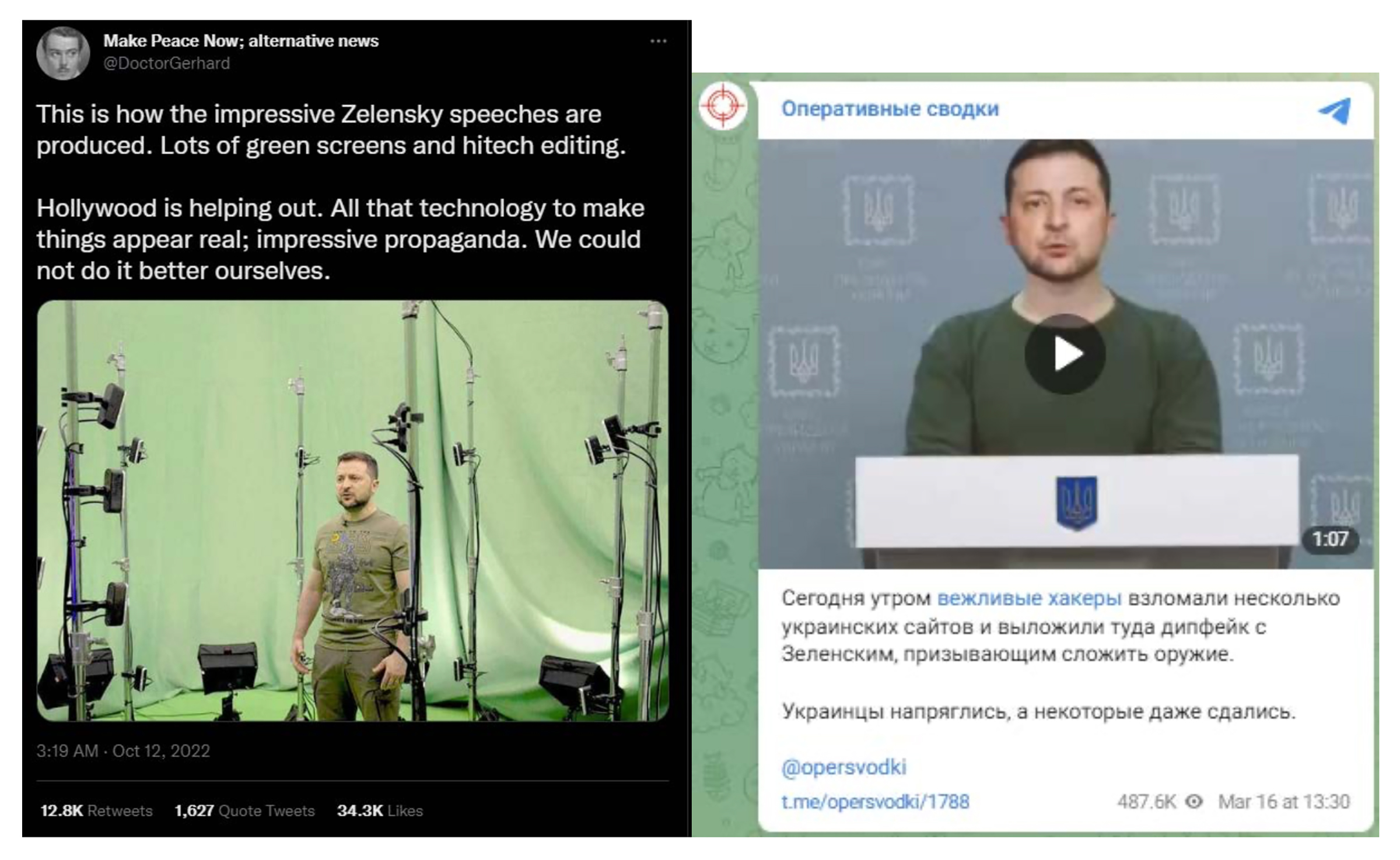

Inside the Kremlin’s Year of Ukraine Propaganda

Three weeks after Russia invaded Ukraine last Feb. 24, a video appeared on a Ukrainian news site that seemed to show President Volodymyr Zelensky imploring his fellow countrymen to stop fighting and urging soldiers to lay down their weapons.

“There is no need to die in this war,” he seemed to say in the video, which was widely circulated on social media and appeared briefly on Ukrainian television with a news ticker suggesting that he had fled the country. “I advise you to live.”

The video—a crude deepfake that had been posted by hackers—was quickly taken down and debunked. It was dismissed by the real Zelensky as a “childish provocation,” and roundly mocked online as an example of Russia’s desperate and often cartoonish attempts to spread fake news. But researchers say the deepfake is just one example of a barrage of disinformation, manipulated imagery, forged documents, and targeted propaganda unleashed by Russia and pro-Kremlin activists that may have had a significant impact on audiences over the last year of war.

“Changing people’s minds and positions is much harder than simply sowing doubt or fear,” says Andy Carvin, a senior fellow at the Atlantic Council’s Digital Forensic Research Lab, which has tracked Russian hybrid warfare activities since 2015 and on Wednesday released a pair of reports analyzing the Kremlin’s information warfare before and after the invasion. “It’s one of the reasons why Kremlin information operations focus so much on essentially generating chaos, causing contagion, causing a loss of morale, or just getting people simply confused about what’s true and what’s not.”

Over the past year, the Kremlin and its allies used a dizzying array of strategies to defend its actions, seed doubt about news from the ground, and push misleading or false narratives to undercut support for Ukraine. Denied the easy victory they had hoped for, Russian officials working to erode global trust in Ukraine as a reliable partner. “To defeat Ukraine on the battlefield,” the report argues, “Russia needed to strangle all sympathy and support for Ukraine as well.”

This screenshot from report "Undermining Ukraine: How the Kremlin Employs Information Operations to Erode Global Confidence in Ukraine" shows examples of conspiracy theories claiming Zelensky left Ukraine

In pursuit of that goal, the Kremlin targeted everyone from Ukrainian citizens to right-wing groups in the U.S. and Europe, countries taking in Ukrainian refugees and those supplying crucial aid, and potentially sympathetic audiences in Africa and Latin America, as well as domestic audiences in Russia itself. Russia’s techniques for spreading these narratives included the use of fake accounts, manipulated imagery like deepfakes, forged documents, and videos with fake news tickers purporting to be from respected brands like the BBC or Al Jazeera. In other cases, operatives simply aimed to increase mistrust in foreign audiences about the credibility of Ukraine’s government and the effectiveness of its military.

While many of these efforts may seem inept to digitally savvy Western observers, it’s a mistake to depict Russia as “losing” the information war, says Carvin, who oversaw the project. “There really isn’t a single information war going on,” he says. “Russia and Ukraine are fighting multiple battles, but Russia has the resources to create customized messages to different audiences all over the globe…And in some parts of the world, their messages resonate better than others.”