Click Here for INL News Amazon Best Seller Books

INLTV Uncensored News

INLTV is Easy To Find Hard To Leave

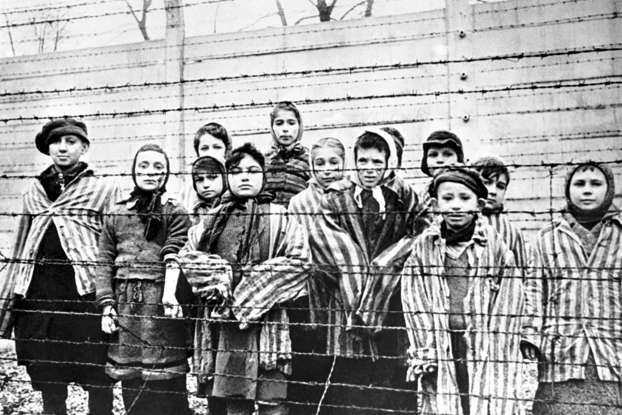

Claims of Russian Concentration Camps Being Built In Occupied Ukraine

Russian forces have been constructing concentration camps in occupied Ukraine according to the Prime Minister of Poland.

Click Here for INL News Amazon Best Seller Books

Click Here for the best range of Amazon Computers

Click Here for INL News Amazon Best Seller Books

Amazon Electronics - Portable Projectors

Polish PM accuses Russia of building concentration camps in Ukraine (msn.com)

An end that is a beginning

How bad is the situation for Ukrainian citizens in the occupied territories?

A matter of symatics

While Russia may claim these new facilities will be penal colonies, it is quite clear they will be something wholly more sinister. Though the world once said never again, it appears as if we will see the mistakes of the twentieth century repeated in the twenty-first century.

"Russia plans to build 25 prisons and three forced labor camps in occupied areas of Ukraine

| International | EL PAÍS English Edition"

Russia plans to build 25 prisons and three forced labor camps in occupied areas of Ukraine

The Russian prime minister has ordered the construction of a large network of prisons to control the population in the illegally annexed territories.

The Kremlin is aiming to deepen its control of Russian-occupied zones in Ukraine by building a large prison network. The Russian government is planning to build 25 prisons and three forced labor camps in the four territories it illegally annexed last year: Zaporizhzhia, Kherson, Donetsk and Luhansk. The main goal of the plan is to control the population in these areas. To achieve this objective, Moscow has also officially created a new department of the federal security service (FSB) in the eastern region of Donetsk.

Under the decree, signed by Russian Prime Minister Mikhail Mishustin, 12 penal colonies (as general regime prisons are known in Russia) will be set up in Donetsk, seven in Luhansk, three in Kherson and another three in Zaporizhzhia. The order also includes the construction of four medical prisons, one for each territory, as well as three forced labor camps: two in Luhansk and one in Donetsk. Moscow has not provided details on many inmates can be housed in these facilities.

The decree states that the new prisons will be built without additional budget, under changes made to Russia’s prison system plan, which runs until 2030. It is a tenuous plan, given the already serious problems facing prisons in Russia. In 2020, the Council of Europe denounced conditions in Russian detention centers, which suffer from overcrowding and lack of resources: Moscow spends less per inmate than other countries in Europe.

The Russian government ordered the Federal Penitentiary System to have all the legal documents for the new prisons ready within three months.

The move comes just days after Kremlin-imposed authorities in Donetsk announced the creation of a new FSB department in the area. Russia’s secret service had been operated in the territory in a de facto manner since the 2014 Donbas war between the Ukrainian army and Moscow-backed separatists broke out, but it did not have official representation until now.

The FSB in Donetsk will be led by General Oleg Bolomozhnov, a senior Russian commander who has served in the secret service since 1991. When the Donbas war began, he was director of the FSB in Tuva, a Russian republic in Siberia. He later took command of the Magadan provinces in the far eastern part of Russia, and of the city of Saratov, which is a major port on the Volga River.

When Russian President Vladimir Putin announced the Russian offensive in Ukraine on February 24, he said: “Our plans do not include the occupation of Ukrainian territories. We are not going to impose anything on anyone by force.” Now, almost a year later, he is planning a massive expansion of the prison network that already existed in the Ukrainian territories. This is despite the fact that, while Russian troops control most of Luhansk, they only partially control the other three regions.

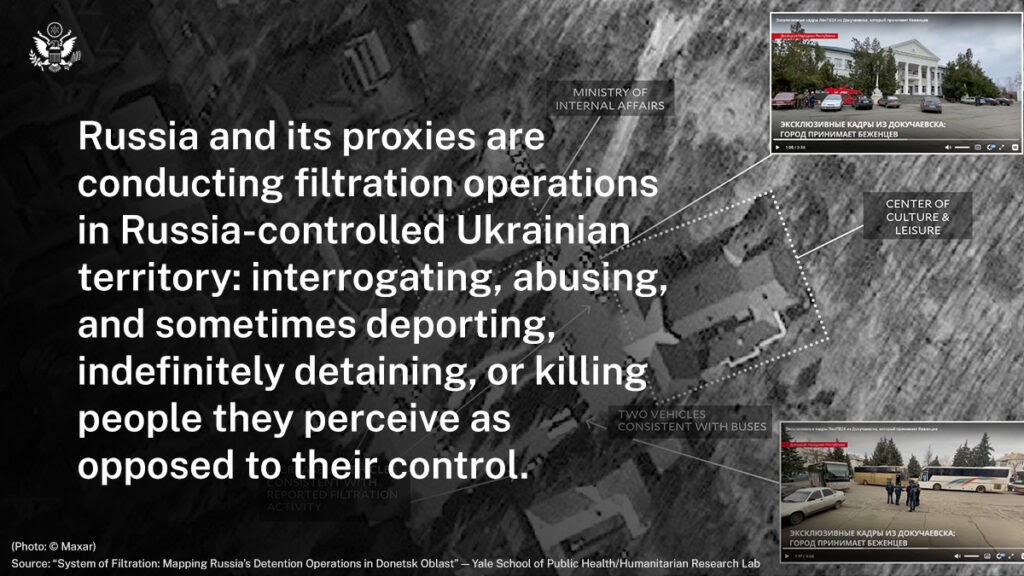

Exposing human rights abuses associated with Russia’s filtration operations in Ukraine

“Filtered. The word does not begin to convey the horror and the depravity of these pre-meditated policies,” said U.S. Ambassador to the United Nations Linda Thomas-Greenfield during a September 7 U.N. Security Council Meeting.

Thomas-Greenfield detailed for the council the numerous mounting and credible reports of the Russian government’s filtration sites in parts of eastern Ukraine that are controlled or occupied by Russia and relocation centers within Russia. Some of these sites were documented in a recent report from Yale’s Humanitarian Research Lab.

Human rights abuses in eastern Ukraine

The Yale report identified 21 credible filtration sites in Ukraine’s Donetsk oblast alone, though more may exist across other Russia-controlled parts of Ukraine. Thomas-Greenfield explained that at these filtration locations, Russian authorities or proxies will reportedly search, interrogate, coerce and sometimes reportedly torture Ukrainian citizens.

“But these horrors are not limited to the centers that have been set up,” she said, “filtration may also occur at checkpoints, routine traffic stops, or on the streets.”

Sources including the Russian government indicate that Russian authorities have interrogated, detained, or deported between 900,000 and 1.6 million Ukrainian citizens, including children, from their homes to Russia.

The United States estimates that in July alone, more than 1,800 children were transferred from Russian-controlled areas of Ukraine to Russia — some separated from their families or taken from orphanages and then put up for adoption in Russia.

Adults considered by Russia and its proxies to be threatening — because of perceived allegiance to Ukraine — are “disappeared” or detained in conditions where human rights abuses run rampant. Thomas-Greenfield recounted how a Ukrainian witness said she overheard a Russian soldier say, “I shot at least 10 people” who did not pass the filtration process.

Russia’s motives for filtration

Why is the Russian government engaging in filtration operations in Ukraine?

Thomas-Greenfield says it’s because they’re preparing to annex additional territory in Ukraine.

“The goal is to change sentiments by force,” she said. “To provide a fraudulent veneer of legitimacy for the Russian occupation and eventual, purported annexation of even more Ukrainian territory.”

The United States calls on the United Nations and its allies to urge Russia to give independent observers, including international and nongovernmental organizations, and humanitarian organizations access to observe filtration sites and relocation centers in Ukraine and Russia for themselves.

“Until Russia provides that access, we will have to rely on the evidence we have accumulated and the brave testimony of survivors,” she concluded. “The picture they paint, alongside the mounting reports, is chilling.”

Russia is likely to leave the conflict smaller than before

"Putin started this war to create a Greater Russia,” wrote Timothy Ash, “but the likely net effect will be a Lesser Russia."

"Russia’s Filtration Operations and Forced Relocations - United States Department of State"

https://www.state.gov/russias-

Russian officials and proxy authorities in Russia-controlled areas of Ukraine are undertaking a monumental effort to “filter” the population as a means of suppressing Ukrainian resistance and enforcing loyalty among the remaining population.

The United States condemns Russia’s “filtration” operations, forced deportations, and disappearances in Russia-controlled areas of Ukraine in which Russia’s forces and proxies have interrogated, detained, and forcibly deported Ukrainian, according to a broad range of sources, between 900,000 and 1.6 million Ukrainian citizens, including thousands of children.

Ukrainian citizens are being taken to filtration camps in a concerted effort to suppress their resistance. Many Ukrainian citizens are facing forced deportations, arbitrary detentions, and torture and other abuses.

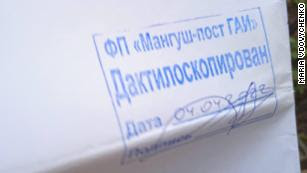

While at filtration camps, Ukrainian citizens are often strip-searched for “nationalistic” tattoos, photographed, and have their fingerprints taken. Ukrainian citizens have had their passports confiscated and their cell phones searched, with Russia’s forces sometimes downloading their contact lists.

There is evidence that Russia’s forces have interrogated, detained, and forcibly deported to Russia an estimated hundreds of thousands of Ukrainian citizens, including unaccompanied children, from their homes, often sending them to remote regions in Russia.

The United States has information that officials from Russia’s Presidential Administration are overseeing and coordinating filtration operations. Russia is also using advanced technology to facilitate filtration processes, including for the purposes of collecting data on Ukrainian citizens undergoing filtration.

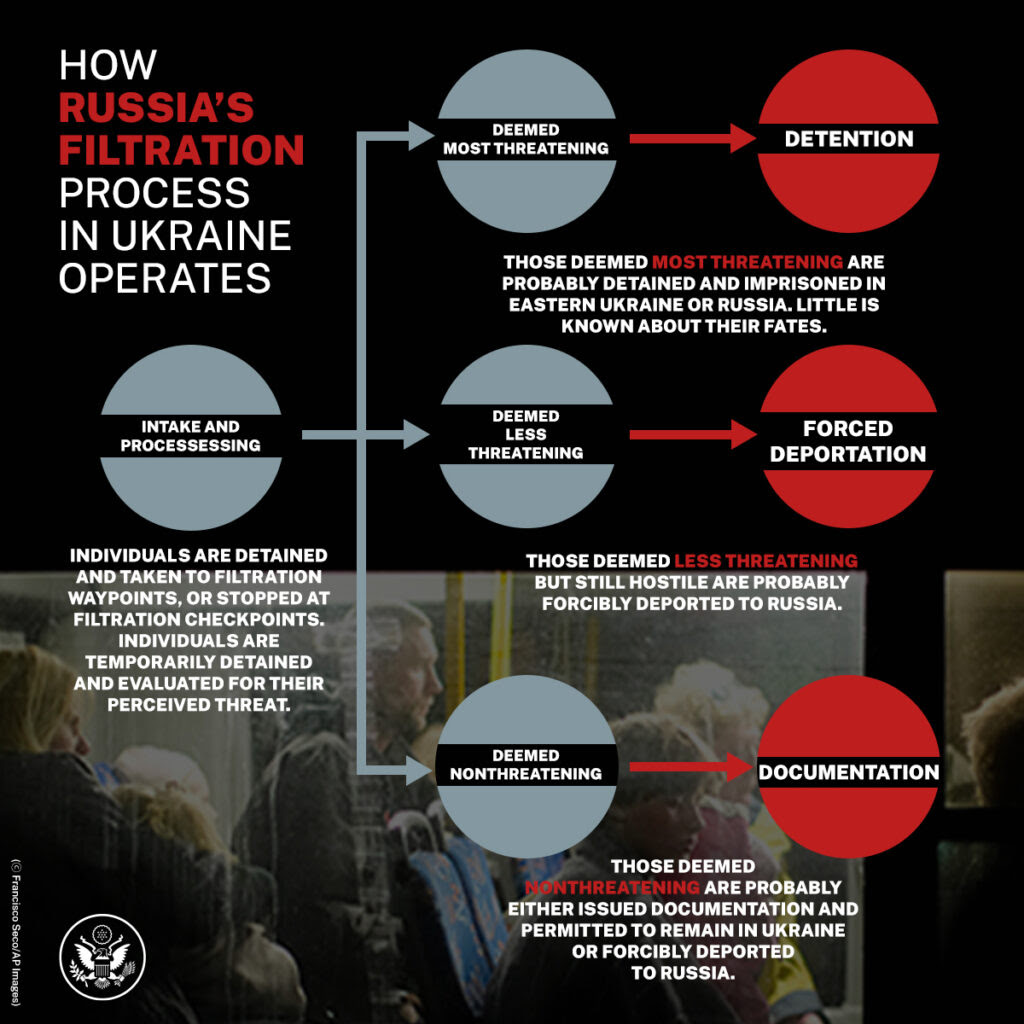

INTAKE AND PROCESSING

Individuals are detained and taken to filtration waypoints, or stopped at filtration checkpoints. Individuals are temporarily detained and evaluated for their perceived threat.

DETENTION

Those deemed most threatening are probably detained and imprisoned in eastern Ukraine or Russia. Little is known about their fates.

FORCED DEPORTATION

Those deemed less threatening but still hostile are probably forcibly deported to Russia.

DOCUMENTATION

Those deemed nonthreatening are probably either issued documentation and permitted to remain in Ukraine or forcibly deported to Russia.

As part of this effort, the United States has information that over the course of July, more than 1,800 children were reported to have been transferred from Russia-controlled areas of Ukraine to Russia. Once in Russia, some reports indicate that children undergo psychological “rehabilitation” and are forced to complete unspecified educational projects.

Thousands of Ukrainian children were reported to have been transferred to Russia. Once in Russia, some reports indicate that Ukrainian children undergo what Russia refers to as psychological “rehabilitation” and are forced to complete unspecified educational projects.

Some of these children have no identity documents or information on the location of their parents. As part of this forced deportation, plans are being developed to place orphaned Ukrainian children with foster families in Russia, in collaboration with other executive agencies in the Russian government.

Children have been evacuated from Mariupol to Russia-controlled areas of Ukraine, and then to Russia. Some children lack any identity documents or information on the location or whereabouts of their parents.

To facilitate the forced deportation and resettlement of children, officials in Russia-controlled areas of Ukraine are developing administrative arrangements to place orphans with families in Russia, in collaboration with Russian executive agencies.

Separately, as of July, Russian officials reportedly forced prisoners in a Russia-held area of Ukraine to apply for Russian citizenship. Prisoners who refused to apply were subjected to physical and psychological abuse.

The United States supports all international efforts to examine mounting evidence of atrocities and other abuses in Ukraine, including fact-finding missions conducted by the International Criminal Court, the United Nations, the Experts Missions established by invocation of the OSCE’s Moscow Mechanism, and other efforts. We also support a wide range of documentation initiatives that can support such investigations.

Russia is doing what Nazi Germany did

Mateusz Morawiecki accused Russian President Vladimir Putin of constructing "camps" in Ukraine similar to those built in Poland 75 years ago by Nazi Germany.

Mateusz Morawiecki's comments

"On the anniversary of the liberation of the Nazi German death camp Auschwitz-Birkenau,” Morawiecki wrote on his official state Facebook page, “let us remember that to the east Putin is building new camps."

"Inside Russian filtration camps, Ukrainians undergo torture and abuse"

People evacuated from the Azovstal plant and adjacent houses in Mariupol arrive at a temporary accommodation center in the village of Bezimenne in Donetsk, May 1, 2022. Both the Russian and Ukrainian militaries say more than 100 people were evacuated from the besieged city of Mariupol in Ukraine but differ on the exact number and other details.

Russian filtration camps: ‘Black holes of human rights abuses’ where Ukrainians face torture and loyalty tests

The camps may be part of a broader plan of cultural genocide by Russia against Ukraine, experts warn.

Almost since the war began, Ukrainians have accused Russian forces of detaining civilians, interrogating them and in many cases forcing them not only from their homes but from their country.

Now, new details are emerging about the scope and scale of Russia’s use of “filtration camps,” makeshift detention centers Russia and proxy forces use to hold, interrogate and deport hundreds of thousands of Ukrainians. A growing number of experts

"These sites are operating in Russian-occupied territories of Ukraine and are believed to be black holes of human rights abuses."

...... Kristina Hook, assistant professor of conflict management, Kennesaw State University

Grid reviewed firsthand accounts from local news reports, Ukrainian and Russian government statements, international human rights reports, intelligence reports, satellite imagery and videos posted to social media to gain a better understanding of the truth on the ground. Much remains unknown about the camps’ operations or the fate of thousands of Ukrainians who have not been heard from since being taken to the camps.

Russia has moved an estimated 1.5 million Ukrainians, including over 200,000 children, to Russia and Russian-controlled areas of Ukraine, according to both Russian and Ukrainian

Russia’s troubling history of filtration camps

The filtration camps appear to serve purposes similar to Russian and Soviet camps in earlier conflicts, from World War II to the Chechen wars of the 1990s: to identify civilians who they believe can assimilate into Russian culture and Russian rule, and punish or remove those who won’t.

“Filtration camps are rooted in Soviet and Russian history,” said Khrystyna Holynska, a defense and policy researcher at the Rand Corporation. “It was a way to, first, get rid of those who could pose a threat to the regime by resisting it. And secondly, it is a way to spread fear and sow distrust among the rest to prevent them from even thinking about resisting.”

Some of those who pass the test of loyalty are freed; others have been kept in these camps in Russian-held territory or taken to Russia.

The growing number of accounts has led to widespread condemnation.

“Evidence is mounting that Russian authorities are detaining or disappearing thousands of Ukrainian civilians who do not pass ‘filtration,’” Secretary of State Antony Blinken said in a press statement.

An apparent Russian filtration center in the village of Bezimenne in Donetsk, Ukraine, on May 1, captured by a Chinese news photographer. Ukrainians evacuated from the Azovstal plant and adjacent houses in Mariupol were reportedly taken to this location

The Organization for Security and Co-operation in Europe (OSCE) described Russia’s use of the filtration and deportation system as a war crime: “Mass forcible transfers of civilians during a conflict to the territory of the occupying party are prohibited under the 1949 Geneva Conventions.” The OSCE said the practice was “somewhat reminiscent of the extraordinary renditions used in the so-called war against terrorism,” referring to the U.S. mistreatment of detainees after 9/11. For historians and others with long memories, the system has invited more direct comparison to the infamous Gulag prison system created by the Soviet Union during the rule of Joseph Stalin.

“The ‘filtration’ camp language invokes loaded Russian words tracing back to World War II-era camps,” said Kristina Hook, an assistant professor of conflict management at Kennesaw State University. “Today, these sites are operating in Russian-occupied territories of Ukraine and are believed to be black holes of human rights abuses.” Hook believes the filtration camps are part of a broader genocidal effort by Russia in Ukraine to erase Ukrainian national identity.

The numbers

Since Russia’s invasion of Ukraine, both sides have inflated statistics and exaggerated claims to suit their narratives. But in terms of the sheer number of Ukrainians who have been “forcibly deported” (according to Ukraine) or “emigrated” (according to Russia), there is some agreement. In May, a Russian official acknowledged that “1,426,979 people, of which 238,329 are children,” had been “evacuated from dangerous areas of the republics of Donbas and Ukraine to the territory of the Russian Federation.” It’s broadly assumed that the Russians delivered most civilian deportees to filtration camps.

Lyudmila Denisova, the former Ukrainian Parliament commissioner for human rights, reported that Russia had deported 1,377,925 Ukrainians, 232,480 of whom were children, as of May 21. That number has since grown to over 1,700,000 Ukrainians as of June, according to the OSCE.

This accounts for those who have likely been through the camps and “released.” Questions remain about those that the Russian government decides to hold.

Stories from the camps

After months of mostly murky, secondhand accounts, multiple stories from the “filtration camps” have begun to emerge.

“There were 36 of us in a cell for six people,” Yevgeny Malyarchuk, a businessman from Mariupol, told Current Time TV, a Prague-based, Russian-language TV station operated by Radio Free Europe. “At the same time, not everyone could lie down, even sit down. Slept in several shifts. It was very hard.”

Malyarchuk said he was attempting to deliver aid to people during the Russian siege of Mariupol when he was captured and brought to a filtration camp. He said he was held for 100 days in a former penal colony in the Ukrainian town of Yelenovka, outside of Donetsk.

Other firsthand accounts describe humiliating interrogations that include being forced to strip naked so that Russians could check for tattoos that might then be taken as “evidence” for opposition to Russia or support for the Ukrainian resistance.

Russian forces and pro-Russian officials in eastern Ukraine have also searched detainees’ mobile electronic devices for anti-Russian sentiment in the form of pro-Ukrainian internet pages and social media groups, former detainees told Politico. A Ukrainian woman told CNN of her experience at a filtration camp: “Once you surrender your phone, they check you in for the first phase of the process. They photograph you from all angles, for facial recognition I suspect. Next you give them your fingerprints and, strangely, palm prints. I don’t know why.” She added that the Russians entered her details in a database. “The next stage, you go in for questioning.”

According to the Ukrainian non-governmental organization Crimea SOS, “In some instances, people are forced to sign testimonies that they were interrogated and tortured by Ukrainian forces.”

A group of Ukrainian aid workers captured by Russian forces and brought to the same former prison colony outside of Donetsk described the conditions there to Mediazona, an independent Russian publication.

The group, whose members were released after several weeks, reported beatings, sadistic prison guards, and minimal food or water at their filtration camp. They said the complex held both prisoners of war and civilians. They described the leadership of the prison camp by name and recalled details of their cruelty.

“Evsyukov Sergey Vladimirovich, in my personal opinion, is one of the worst executioners who manages this entire camp,” said Stanislav Glukshov, a transportation worker with the group. “[Vladimirovich] repeatedly told us that we would stay there for at least ten years, that our children, our families would be told that we flew into space, or that we are military pilots who died.”

“We will detain all bandits and fascists”

A review of news reports and government analyses indicates Russia and allied separatist groups have created filtration camps at police stations, decommissioned prisons and tent encampments. Most are in the People’s Republic of Luhansk and People’s Republic of Donetsk, the regions in eastern Ukraine that have been controlled by Russia-backed separatists since before Russian President Vladimir Putin’s February invasion

The United States last month released a declassified intelligence report on Russia’s “Systemic Filtration Operations,” which detailed much of what American analysts have gleaned about the program. The report, which a Defense Department official called “chilling,” identifies 18 camps.

Last week, Poland’s intelligence service publicized the coordinates of five locations in Ukraine it believed housed filtration camps. Grid reviewed Maxar satellite imagery of the locations, which showed nondescript buildings, a tent city, and lines of buses and other vehicles. Russia has not denied the existence of filtration camps — but challenged the suggestion that they are punitive in nature. The Russian Embassy in Washington, D.C., framed the camps as part of an effort to foil saboteurs.

“We emphasize: in this case, we are talking about checkpoints for civilians leaving the zone of active hostilities,” the embassy said. “In order to avoid sabotage operations by the Ukrainian national battalions, servicemen of the [Russian Federation] Armed Forces carefully inspect vehicles heading to safe regions.

“We will detain all bandits and fascists. The Russian military does not create any barriers for the civilian population, but helps [them] to stay alive, provides them with food and medicine.”

The embassy has since referred to reports about the camps as “low-quality Western misinformation.” It did not respond to inquiries from Grid for this story.

Western analysts and diplomats don’t buy the Russian explanations. The camps are “designed to weed out those who cannot be forcibly Russified, that is, those who will not accept the Kremlin’s propagandistic claims that Ukrainian national identity is an artificial construct,” Kennesaw State’s Hook wrote in Foreign Affairs magazine last week. Hook and others believe the camps are one aspect of a broader Russian effort to commit genocide against Ukrainians.

Beyond the camps, mystery and danger

Detainees whom the Russians believe have connections to the Ukrainian military or security services appear to receive the harshest treatment, most likely including being sent to prisons in eastern Ukraine or Russia. In their July report, U.S. officials cautioned that “little is known about their fates.”

Ukrainians without apparent ties to the military, but whom the Russians consider of possible concern — perhaps for their pro-Ukrainian sentiment or resistance to Russian occupation — appear to be leading candidates for forcible deportation to Russia.

Those detainees who are not considered a threat receive official documentation and are permitted to leave the camps. At that point they face a choice: remain in the Russian-occupied areas of Ukraine or be forcibly transported into the Russian interior.

Meanwhile, it appears that Russia has moved many Ukrainian civilians from the camps to far-flung spots in Russia.

One woman told CNN that at the Russian border, those with no family or friends in Russia were being sent nearly 1,000 miles east, to the city of Vladimir. But other reports suggest Ukrainians have been sent on even longer journeys.

A May investigation by British outlet I News found 66 “former Soviet sanatoriums, children’s wilderness camps, hostels and orphanages,” often in extremely remote parts of Russia, were the final destinations for many Ukrainians who had passed through the filtration camps.

The news site found a group of 300 people who had been sent to Vladivostok, the largest city in Russia’s far east, thousands of miles from Ukraine, after a seven-day train trip on the Trans-Siberian Express. Vladivostok is closer to Tokyo than to Moscow.

While Ukrainians are free to leave such sites, the remoteness and lack of resources can effectively force them to remain, according to the I News investigation.

The fate of children

Human rights advocates believe Russians have separated Ukrainian children from their parents at the filtration camps and placed Ukrainian orphans with Russian families.

Michelle Bachelet, the high commissioner for human rights at the United Nations, told the Human Rights Council that her office is looking into allegations that children in orphanages had been taken to Russia. According to UNICEF, Ukraine had more than 91,000 children in orphanages before the Russian invasion.

Deputy head of the Zaporizhzhia Regional Military Administration Zlata Nekrasova stays by Alisa, 4, who travelled unaccompanied during the recent evacuation from the Azovstal steelworks, Zaporizhzhia, southeastern Ukraine. The girl and mother, a healthcare worker, who had been sheltering at one of the Azovstal bunkers, were separated by Russian invaders at a filtration camp in the so-called 'DNR'. (Dmytro Smolyenko/Ukrinform/Future Publishing via Getty Images)

BuzzFeed News reported that Russia is transporting Ukrainian children across the border, a violation of international law. The outlet recounted the harrowing story of a grandmother searching for her missing 3-year-old granddaughter and described Russians “evacuating” children from Ukrainian orphanages to Russia. Ukrainian children from orphanages are being adopted by Russian families, according to the report.

What we don’t know

Those who have studied the allegations about the filtration camp system are quick to point out that these are stories from the survivors — the people who have passed through the system and emerged to speak about the experience. Virtually everything we know about filtration camps is based on their accounts.

There are likely hundreds of thousands of other Ukrainians still held — either in the Russian-occupied regions of Ukraine or inside Russia itself. There are those in Russia who are technically “free to leave” but likely lacking any means to do so. And there are those children who have been taken to Russia.

“Most of the information on what is going on in these camps we get from the people who managed to ‘pass’ the filtration,” said Holynska at Rand. “They report on what they could observe or overhear. They talk about the inhumane conditions they had to endure until they were released.

“We have very limited information on those who are not released.”

Thanks to Lillian Barkley for copy editing this article.

Do you have information about filtration camps? We want to hear from you. Email us at This email address is being protected from spambots. You need JavaScript enabled to view it., or on WhatsApp or Signal at 202-999-9679.

Satellite image showing red building and blue tents

A satellite view shows cars outside the filtration camp at Bezimenne, Ukraine, on March 2

Russia has been using camps since the beginning of the war

Since the beginning of the war in Ukraine, Russian forces have been using a variety of camps to hold, and then filter, Ukrainian citizens that fell under their control.

"'You can't imagine the conditions' -

Accounts emerge of Russian detention camps - BBC News"

https://www.bbc.com/news/

- By Toby Luckhurst & Olga Pona BBC News, Lviv 25 April 2022

-

Olena and Oleksandr in the relative safety of Lviv, after escaping Mariupol

"You can't imagine how horrible the conditions were."

Evgeniy and Valentyna managed to survive by hiding in their basement

Oleksandr and Olena are two of the lucky few who recently managed to escape from Mariupol, which is now almost under full Russian control after weeks of bombardment.

The city is effectively sealed off from the world, and information about what is happening inside is difficult to confirm independently.

But the pair, and others, have given chilling accounts of life in Russia's so-called filtration camps, set up outside Mariupol to house civilians before they are evacuated.

Oleksandr and Olena, speaking from the relatively safe western city of Lviv, say they ended up at one of the centres when they tried to escape the city. After walking from their home to an evacuation point, they were driven to a Russian refugee hub at a former school in the village of Nikolske, north-west of Mariupol.

"It was like a true concentration camp," Oleksandr, 49, says.

The centres have been compared by Ukrainian officials to those used during Russia's war in Chechnya, when thousands of Chechens were brutally interrogated and many disappeared.

Oleksandr and Olena were fingerprinted, photographed from all sides, and interrogated for several hours by Russian security officers - "like in a prison", he says.

They worried that the Russians would look at their phones, and so they cleared all evidence from their devices of anything to do with Ukraine - including photos of their daughter in front of a Ukrainian flag.

They were right to worry. Oleksandr says that during their interrogation, Russian security officers examined photographs, phone call history and contact numbers on their devices for links with journalists or government and military officials.

"If a person was suspected of being a 'Ukrainian Nazi', they took them to Donetsk for further investigation or murder," says Oleksandr, although the BBC has not been able to verify this claim. "It was very dangerous and risky. Any small doubt, any small resistance - and they could take you to the basements for interrogation and torture. Everybody was afraid to be taken to Donetsk."

President Vladimir Putin has stated one of the aims of his invasion is to clear Ukraine of Nazis, and Russian propaganda has made numerous baseless allegations that Ukraine is somehow aligned with Nazism.

Eventually the pair were detained and put on a list for evacuation. But the ordeal did not stop there.

A secret escape

Elderly people slept in corridors without mattresses or blankets, Olena says. There was only one toilet and one sink for thousands of people. Dysentery soon began to spread. "There was no way to wash or clean," she says. "It smelt extremely awful."

Soap and disinfectant ran out on the second day they were there. Soon, too, did toilet paper and sanitary pads.

Olena and Oleksandr were told they had permission to leave on the 148th evacuation bus. But a week later, just 20 buses had left the facility.

In contrast, there were many buses organised to go to Russian territory. Authorities even tried to force the couple on to a coach heading east, they say. In the end Olena and Oleksandr felt compelled to seek the help of private drivers, who they feared could be Russians or collaborators.

"We didn't have any choice - either be forcibly deported to Russia or risk it with these private drivers," Olena says.

It's a dilemma that Mariupol's mayor, Vadym Boychenko, recognises. "Many buses of civilians go to Russian rather than Ukrainian territory," he told the BBC, over the phone. "From the beginning of war, [the Russians] didn't allow any way to evacuate civilians. It's a direct military order to kill civilians," he claimed.

Oleksandr and Olena's driver managed to get them from their filtration camp to the Russian-occupied city of Berdyansk - through "fields, dirt roads, narrow pathways behind all the checkpoints", Olena says, because they didn't have the proper documents to pass a Russian inspection.

They then spent three days looking for a route out before finding another driver who was willing to risk everything to get them to Ukrainian-controlled territory. He managed to get around 12 Russian checkpoints and safely deliver them to Zaporizhzhia. The couple then took an overnight train to Lviv.

"From filtration camps you can only escape using these risky local private drivers," Oleksandr says. "Fortunately, there are good people among them."

Camps like 'ghettos'

Arriving in Lviv on the same day were Valentyna and her husband Evgeniy. They also managed to flee Mariupol last week. They were boarding a coach to a smaller city in western Ukraine - desperate for safety after their ordeal.

The situation in Mariupol, they said, had become dire. They survived by sheltering in a basement, living of tinned goods, a handful of potatoes they grew in their garden, and water taken from the boiler.

The filtration process was speedy for them, says Valentyna, 58, perhaps because of their age and because Evgeniy has a disability. But it was far worse for younger people, she said.

"The filtration camps are like ghettos," she says. "Russians divide people into groups. Those who were suspected of having connections with the Ukrainian army, territorial defence, journalists, workers from the government - it's very dangerous for them. They take those people to prisons to Donetsk, torture them."

She and Evgeniy also say many were sent from the filtration camps to Russia. Sometimes people were told they were destined for Ukrainian-controlled territory, they say, only for the coach to head to Russian-held territory instead.

Like Oleksandr and Olena, Valentyna says it was only because of their driver that they managed to escape.

"When we finally [escaped] and saw the Ukrainian fighters and the flag, when we heard Ukrainian language, everyone in the bus started to cry," she said. "It was just unbelievable that we stayed alive and finally fled from hell."

Both couples have now escaped Mariupol, a city that has become a symbol of the resistance and the suffering of Ukraine after the Russian invasion. Now they face an uncertain future - just four of the 11 million Ukrainians displaced by the conflict.

"The city does not exist anymore," Valentyna says. "Even walls. Just huge piles of ruins. I could never have imagined such violence."

Related topics

What's actually happening in Ukraine?

“Ukrainian citizens are being taken to filtration camps in a concerted effort to suppress their resistance,” according to a U.S. State Department report on the issue.

Ukrainians face deportation and detention

“Many Ukrainian citizens are facing forced deportations, arbitrary detentions, and torture and other abuses,” the report continued.

Subject to strip searches to find the undesirables

While at Russia’s filtration camps, Ukrainian citizens have been subjected to strip searches and have had any nationalistic tattoos photographed and logged.

Ukrainians detained in Russia’s filtration camps were also forced to have their fingerprints taken, a situation eerily familiar to what many Jews faced under Nazi Germany.

What Are Putin’s ‘Filtration Camps’ And Why Are They Concerning?

Ten months of Putin’s war in Ukraine have seen a litany of atrocities including summary executions, unlawful confinement, torture, ill-treatment, rape and other sexual violence, forced displacement of people, removal of children, and illegal adoptions, among others. These atrocities meet the legal definitions of crimes against humanity, war crimes, and of the serious risk of genocide and incitement of genocide. Over recent months, yet another aspect of the atrocities came into the spotlight, the issue of the so-called “filtration camps.”

What are filtration camps?

Office of the High Commissioner for Human Rights (OHCHR) indicated that filtration camps are a common place for egregious human rights violations, including of the rights to liberty, security of person and privacy. OHCHR documented that such filtrations involve “body searches, sometimes involving forced nudity, and detailed interrogations about the personal background, family ties, political views and allegiances of the individual concerned. They examined personal belongings, including mobile devices, and gathered personal identity data, pictures and fingerprints. In some cases, those awaiting filtration spent nights in vehicles or in unequipped and overcrowded premises, sometimes without adequate access to food, water or sanitation. We are particularly concerned that women and girls are at risk of sexual abuse during filtration procedures.”

During the U.N. Security Council meeting in September 2022, Ms. Oleksandra Drik, Coordinator for international cooperation, Center for Civil Liberties, cited several cases of filtrations. One young man, Taras Tselenchenko, 21, from Mariupol, and his 80-year-old grandmother, were subjected to the filtration process twice. “He was fingerprinted, photographed, interrogated and psychologically pressured through interrogation by a former member of the Ukrainian military, along with a Russian wearing civilian clothes and holding a baseball bat in his hands.” Marya Vychenko, 17, was subjected to filtration in a camp in Mangush. Apart from the usual humiliating procedure, “she was also sexually harassed during her interrogation but was spared violence because the Russian soldiers did not find her pretty enough. ‘Maybe the next one will be prettier’, they said to her.”

Those who do not pass filtration may be detained in filtration camps for months. From there they may be sent to detention centers or prisons in the occupied territories or Russia. A survivor, 16-year-old Vadym Buriak, testified that he “had to live in a prison cell without even a working toilet. Almost daily, he would hear and see the torture of Ukrainian prisoners of war and then be forced to clean up the blood in the torture rooms.”

Reports suggest that Russian authorities have interrogated, detained and forcibly deported between 900,000 and 1.6 million Ukrainian citizens from their homes to Russia. It is a systematic, planned and organized crime. Such filtration camps are not a new development. Indeed, Russia has been using them in the occupied territories since the invasion in Ukraine in 2014.

As evidence of egregious human rights violations is being collected and preserved, specific focus must be paid to the situation in filtration camps and what happens to the individuals who are processed there.

Follow me on Twitter or LinkedIn. Check out my website or some of my other work here.

Dr. Ewelina U. Ochab is a human rights advocate, author and co-founder

Confiscated passports

“Ukrainian citizens have had their passports confiscated and their cell phones searched,” the US State Department report added, “with Russia’s forces sometimes downloading their contact lists.”

"‘Absolute evil’: inside the Russian prison camp where dozens of Ukrainians burned to death | Ukraine | The Guardian" https://amp.theguardian.com/

‘Absolute evil’: inside the Russian prison camp where dozens of Ukrainians burned to death

Entrepreneur Anna Vorosheva accuses Moscow of murder after spending 100 days in the Olenivka detention centre

Screams from soldiers being tortured, overflowing cells, inhuman conditions, a regime of intimidation and murder. Inedible gruel, no communication with the outside world, and days marked off with a home-made calendar written on a box of tea.

This, according to a prisoner who was there, is what conditions are like inside Olenivka, the notorious detention centre outside Donetsk where dozens of Ukrainian soldiers burned to death in a horrific episode late last month while in Russian captivity.

Anna Vorosheva – a 45-year-old Ukrainian entrepreneur – gave a harrowing account to the Observer of her time inside the jail. She spent 100 days in Olenivka after being detained in mid-March at a checkpoint run by the pro-Russian Donetsk People’s Republic (DNR) in eastern Ukraine.

She had been trying to deliver humanitarian supplies to Mariupol, her home city, which the Russian army had besieged. The separatists arrested her and drove her in a packed police van to the prison, where she was held until early July on charges of “terrorism”.

Now recovering in France, Vorosheva said she had no doubt Russia “cynically and deliberately” murdered Ukrainian prisoners of war. “We are talking about absolute evil,” she said.

The fighters were blown up on 29 July in a mysterious and devastating explosion. Moscow claims Ukraine killed them with a US-made precision-guided Himars rocket. Satellite images and independent analysis, however, suggest they were obliterated by a powerful bomb detonated from inside the building.

Russia says 53 prisoners were killed and 75 injured. Ukraine has been unable to confirm these figures and has called for an investigation. The victims were members of the Azov battalion. Until their surrender in May, they had defended Mariupol’s Azovstal steel plant, holding out underground.

A day before the blast, they were transferred to a separate area in the camp’s industrial zone, some distance from the grimy two-storey concrete block where Vorosheva shared a cell with other women prisoners. Video shown on Russian state TV revealed charred bodies and twisted metal bunk beds.

“Russia didn’t want them to stay alive. I’m sure some of those ‘killed’ in the explosion were already corpses. It was a convenient way of accounting for the fact they had been tortured to death,” she said.

Male prisoners were regularly removed from their cells, beaten, then locked up again. “We heard their cries,” she said. “They played loud music to cover the screams. Torture happened all the time. Investigators would joke about it and ask inmates, ‘What happened to your face?’ The soldier would reply, ‘I fell over’, and they would laugh.

“It was a demonstration of power. The prisoners understood that anything could happen to them, that they might easily be killed. A small number of the Azov guys were captured before the mass surrender in May.”

Vorosheva said there was constant traffic around Olenivka, known as correctional colony No 120. A former Soviet technical school, it was converted in the 1980s into a prison, and later abandoned. The DNR began using it earlier this year to house enemy civilians.

Captives arrived and departed every day at the camp, 20km south-west of occupied Donetsk, Vorosheva told the Observer. Around 2,500 people were held there, with the figure sometimes rising to 3,500-4,000, she estimated. There was no running water or electricity.

The atmosphere changed when around 2,000 Azov fighters were bussed in on the morning of 17 May, she said. Russian flags were raised and the DNR colours taken down. Guards were initially wary of the new prisoners. Later they talked openly about how they were going to brutalise and humiliate them, she said.

“We were frequently called Nazis and terrorists. One of the women in my cell was an Azovstal medic. She was pregnant. I asked if I could give her my food ration. I was told, ‘No, she’s a killer’. The only question they ever asked me was, ‘Do you know any Azov soldiers?’”

Conditions for the female inmates were grim. She said they were not tortured but received barely any food – 50g of bread for dinner and sometimes porridge. “It was fit for pigs,” she said. She suspected the prison governor siphoned off money allocated for meals. The toilets overflowed and the women were given no sanitary products. The cells were so overcrowded they slept in shifts. “It was tough. People were crying, worried about their kids and families.” Asked if the guards ever showed sympathy, she said an anonymous person once left them a bottle of shampoo.

According to Vorosheva, the camp’s staff were brainwashed by Russian propaganda and considered Ukrainians to be Nazis. Some were local villagers. “They blamed us for the fact that their lives were terrible. It was like an alcoholic who says he drinks vodka because his wife is no good.

“The philosophy is: ‘Everything is horrible for us, so everything should be horrible for you’. It’s all very communist.”

Ukraine’s president, Volodymyr Zelenskiy, has called the explosion “a deliberate Russian war crime and a deliberate mass murder of Ukrainian prisoners of war”. Last week, his office and Ukraine’s defence ministry gave details of clues which they say point to the Kremlin’s guilt.

Citing satellite images and phone intercepts and intelligence, they said Russian mercenaries from the Wagner group carried out the killings in collaboration with Vladimir Putin’s FSB spy agency. They point to the fact a row of graves was dug in the colony a few days before the blast.

The operation was approved at the “highest level” in Moscow, they allege. “Russia is not a democracy. The dictator is personally responsible for everything, whether it’s MH17, Bucha or Olenivka,” one intelligence source said. “The question is: when will Putin acknowledge his atrocities.”

One version of events being examined by Kyiv is that the blast may have been the result of intra-service rivalries between Russia’s FSB and GRU military intelligence wings. The GRU negotiated Azovstal’s surrender with its Ukrainian army counterpart, sources suggest – a deal the FSB may have been keen to wreck.

The soldiers should have been protected by guarantees given by Russia to the UN and the International Committee of the Red Cross that the Azov detainees would be properly treated. Since the blast, the Russians have refused to give international representatives any access to the site.

Vorosheva said the Red Cross were allowed into the camp in May. She said the Russians took the visitors to a specially renovated room and did not allow them to talk independently to the prisoners. “It was a show,” she said. “We were asked to give our clothes’ size and told the Red Cross would hand out something. Nothing reached us.”

Other detainees confirmed Vorosheva’s version of events and said the Azov soldiers were treated worse than civilians. Dmitry Bodrov, a 32-year-old volunteer worker, told the Wall Street Journal the guards took anyone they suspected of misbehaviour to a special disciplinary section of the camp for beatings.

They emerged limping and moaning, he said. Some captives were forced to crawl back to their cells. Another prisoner, Stanislav Hlushkov, said an inmate who was regularly beaten was found dead in solitary confinement. Orderlies put a sheet over his head, loaded him into a mortuary van and told fellow inmates he had “committed suicide”.

Vorosheva was freed on 4 July. It was, she said, a “miracle”. “The guards read out the names of those who were going to be freed. Everyone listened in silence. My heart leaped when I heard my name. I packed my things but didn’t celebrate. There were cases where people were on the list, got out, then came back.”

She added: “The people who run the camp represent the worst aspects of the Soviet Union. They could only behave well if they thought nobody was looking.”

Blinken called on Russia to end its systematic filtration of Ukrainians

In a July 2022 statement from Secretary of State Anthony Blinken, America’s chief diplomat called on Russia to end its “systematic filtration and forced deportations” in the Ukranian territory’s it controlled.

Tens of thousands deported to Russia

Blinken also estimated that roughly 900,000 to 1,600,000 Ukrainian citizens had been deported to Russia, including 260,000 children.

"Russian filtration camps: Ukrainians must endure a brutal process to escape Russian-held territory. Here's what that means - CNN"

https://amp.cnn.com/cnn/2022/

Ukrainians must endure a brutal 'filtration' process to escape Russian-held territory. Here's what that means

Kyiv, Ukraine(CNN)"What would happen if we cut off your ear?" the soldiers asked Oleksandr Vdovychenko. Then they hit him in the head.

The punches kept coming whenever his interrogators -- a mixture of Russian soldiers and pro-Russian separatists -- didn't like his answers, he later told his family.

The men asked about his politics, his future plans, his views on the war. They checked his documents, took his fingerprints and stripped him to check if he had any nationalist tattoos or marks caused by wearing or carrying military equipment.

"They were trying to beat something out of him," his daughter Maria Vdovychenko told CNN in an interview.

Maria said her father received so many blows to his head during the interrogation last month that several medical examinations have now confirmed his sight has been permanently damaged.

Yet Oleksandr was one of the lucky ones. He made it through "filtration."

When Russian troops first started taking over villages and towns in eastern Ukraine in early March, following their invasion of the country, evidence began to emerge of civilians being forced to undergo humiliating identity checks and often violent questioning before being allowed to leave their homes and travel to areas still under Ukrainian control.

Three months into the war, the dehumanizing process known as filtration has become part of the reality of life under Russian occupation.

CNN spoke to a number of Ukrainians who have gone through the filtration process over the last two months. Many are too scared to speak publicly, fearing for the safety of relatives and friends who are still trying to escape Russian-held areas.

All of the people CNN spoke to have described facing threats and humiliation during the process. Many have witnessed or know of people who have been picked up by Russian troops or separatist soldiers and subsequently disappeared without a trace.

For most of the people CNN spoke to, the filtration process included document checks, interrogation, fingerprinting and a search. Many were separated from their families. Men were routinely stripped and examined.

Lyudmyla Denisova, the Ukrainian parliament's human rights ombudsman, said earlier this month that Russian forces had created an "extensive network" of places where Ukrainians are being subjected to "filtering."

She said such places have been established "in every occupied Ukrainian city" and that more than "37,000 citizens" have already gone through the procedure.

Nikolay Ryabchenko told CNN he fled Mariupol in mid-March when the city was closed and people were not allowed to move around.

"We found a way to avoid checkpoints and came to Nikolske and we stayed there for a couple of weeks," he said. "I asked everyone I met how to get out and they [said] filtration is obligatory."

Information signs that have been posted in Mariupol after Russian troops took over the city leave no room for doubt: "Evacuation can be carried out if there is a document confirming the passage of the filtration procedure." CNN has seen a photo of one such sign taken by a person who escaped the city.

"Everyone has to go through filtration, both men and women, in order to move around the city freely," 20-year old Karina, another Mariupol resident, who is only being identified by her first name due to security concerns, told CNN.

She has managed to escape Mariupol but her father, who has not yet passed the filtration process and has no idea why, is still there.

A month after being picked up by Russian soldiers on a street in Mariupol, he is still being held in what the self-declared separatist Donetsk People's Republic (DPR) in eastern Ukraine calls a "reception center" at a school in Bezimenne, around 20 miles (32 kilometers) east of Mariupol, he told his daughter.

The separatist-held Bezimenne has been used by Russian troops as a screening facility for refugees from Mariupol and surrounding areas.

In three separate statements published last week, the DPR Territorial Defense said almost 1,000 evacuees from Mariupol have been brought to the Bezimenne center in a three days. It said that as of May 17, more than 33,000 people have gone through the facility.

Earlier this month, the Russian Ministry of Defence released a video showing evacuees from Mariupol arrive in a filtration camp outside the city in busses. The ministry published the videos without saying where the refugees were taken, or when the evacuations took place. CNN has been able to geolocate the footage, and it shows that they were taken to Bezimenne.

Separately, satellite images from Maxar Technologies have showed a tent encampment being erected in the separatist-held Bezimenne as early as in March.

Karina said she had been able to speak to her father who told her that conditions there were appalling.

"Some sleep on the floor, some are luckier [and sleep] on chairs, and some are even luckier and have mattresses in the gym," she said. "There's no opportunity to wash and no normal restroom. All of them were ill because it was too cold to sleep on the floor."

Karina said her father had told her the guards in the center have refused to provide any medicine to the people being held there. They are being fed watery soup and other prison-like food cooked in a field kitchen, he said.

Ombudsman Denisova said the Bezimenne center where Karina's father is being held is just one of several such facilities set up in the Donetsk region. She said Russian troops have established similar filtration camps in Dokuchaevsk, Mykilsky, Mangush, Bezymenny and Yalta.

She accused Russia of using the centers to detain and "wipe out" any "officials, members of the military or the volunteer territorial defense forces, activists or anyone they consider a threat."

Maria Vdovychenko told CNN it looked like the soldiers were trying to find anything they could say was incriminating.

"They were looking for Ukrainian-speaking people, for Ukrainian symbols, tattoos," she said, adding that the soldiers checked her phone, but didn't find anything compromising.

"We have deleted everything because people in the line told us they can look at everything -- contacts, for example, they could call some of your contacts -- and pictures ... For every Ukrainian, it is normal to have pictures in vyshyvanka [traditional Ukrainian embroidered clothing] or with a flag, or near [a] Shevchenko monument [depicting prominent Ukrainian poet, Taras Shevchenko]," Maria said.

"I'm a bandura [traditional Ukrainian instrument] player, it wasn't good idea to show that. So I deleted that, took a couple of new pictures, and deleted my social network profiles," she added.

Michael Carpenter, the US Ambassador to the Organization for Security and Co-operation in Europe (OSCE), said last month there was credible reporting that "Russia's forces are rounding up the local civilian populations in these areas, detaining them in these camps, and brutally interrogating them for any supposed links to the legitimate Ukrainian government or to independent media outlets.

Speaking last week, Carpenter added: "Numerous eyewitness accounts indicate that 'filtering out' entails beating and torturing individuals to determine whether they owe even the slightest allegiance to the Ukrainian state."

Mariupol city council has accused Russian forces of using the filtration centers to identify witnesses to any "atrocities" committed by Russian troops during the battle for the control of the city. CNN could not verify that claim.

The Kremlin has denied using filtration camps to cover up wrongdoing and targeting civilians in Mariupol.

The self-declared DPR has denied accusations by Ukrainian authorities of unlawful detentions, filtration and maltreatment of Ukrainian citizens and said that those arriving at what it calls reception centers are properly fed and provided medical attention.

Karina said that, according to her father, most of the men in the center have no idea why they are being held.

"They were told the filtration would take one to two days maximum and that the [process] is needed to check if they took part in hostilities," Karina told CNN. "They have been trapped there since April 12 and have no idea when they will be released."

That uncertainty makes the process terrifying for Ukrainians trying to flee to safety. Most have no idea what to expect.

Ukrainian social media pages for people stuck in Russian-controlled regions, or their families searching for them, are full of questions about filtration.

Yana, who left Berdiansk in southern Ukraine to stay with relatives in Rostov in Russia, the only place she said she was able to get to, said the process appeared to be completely random. She asked CNN not to publish her last name, fearing retribution.

"Close friends told me that they stood in line for filtration for six days, spent the nights in cars, and yet some passed quickly. I don't know why -- apparently it depends on which shift you will get," she said.

Before the war, Eugen Tuzov was a martial arts instructor in Mariupol. Now he spends most of his time trying to organize transport for people stuck in the Russian-occupied city and the surrounding areas who want to flee to places under Ukrainian control.

He, too, told CNN the filtration process at checkpoints on the roads leading out of Mariupol -- he said there were at least 27 of them -- appeared to be random.

"Everything depends on [the] shift. Someone is lucky, someone comes to a sh*tty shift," he said.

"The DPR people were the worst -- they are disheveled, slovens, sometimes they are drunk already in the morning, behaving terribly. You see man 50, 60 years old and you can see it from his face that he drinks constantly," Ryabchenko told CNN.

Petro Andriushchenko, an adviser to the Mariupol mayor, said in a statement on Monday that Russian troops have set up five filtration points across the city.

Mariupol residents need to pass this procedure in order to receive a certificate allowing them to move around the city, he said, adding: "If this isn't a ghetto, I don't know what is."

Yana said her parents had to undergo filtration at a hospital in Donetsk, where they were taken after being wounded in a strike, having already spent more than two weeks hiding in a shelter in Mariupol with no medical help.

"People came from some service, took their fingerprints, told them this is filtration since they could not walk, but it had to be done, such rules are in the DPR," she said.

Yana said when she and her husband drove out of the area, they had to pass almost 20 checkpoints. "And at almost every checkpoint, they undressed my husband, looked for tattoos and weapons marks and asked whether he had served in the army," she said.

Tuzov said the volunteers in his transport service have similar experiences; he said some were subjected to lie detector tests and that -- as far as he knows -- at least 30 of them were detained during the process. "They were taken at checkpoints. They check phones, social networks, if you wrote something about them ... they take you away," he said.

Tuzov said he doesn't know the fate of those who have been detained. CNN has previously reported that some of those picked up in the process end up being sent to Russia.

Maria Vdovychenko said she and her family -- her parents and younger sister -- waited in Nova Yalta for about 20 days before they were allowed to go through the filtration process.

"We were told we wouldn't be able to get out without that," she told CNN. "They [said] they will just check documents and phones, and we will leave. But it wasn't as easy as they promised."

She said the family queued for two days and two nights without being allowed to leave their car. Finally, Maria and her father were taken to a small wooden structure about 200 meters away. Her younger sister and her mother, who wasn't able to walk, were told to stay in the vehicle.

While waiting to enter the makeshift building, Maria said she felt threatened. "[The soldiers] were talking among themselves. It was scary to listen to what can happen to people who didn't pass the filtration. I will remember it forever."

She said she overheard one of the soldiers guarding the site saying: "'I killed 10, and didn't count further."

The reports coming from these facilities have shocked the international community and the practice was cited as one of the reasons for Russia to be suspended from the UN's Human Rights Council in April. Despite the outrage, evidence from the ground, testimonies from those who escape and statements by the separatist authorities show Russia has only increased its use of filtration since then.

It's not the first time either. During the war in Chechnya, Russian forces used filtration camps to separate civilians from rebel fighters. Legendary Russian investigative reporter Anna Politkovskaya gathered testimony from Chechen civilians detained these centers, revealing brutal interrogation methods, torture and human rights violations. She was murdered in her Moscow apartment building in 2006.

Kyiv, Ukraine(CNN)"What would happen if we cut off your ear?" the soldiers asked Oleksandr Vdovychenko. Then they hit him in the head.

The punches kept coming whenever his interrogators -- a mixture of Russian soldiers and pro-Russian separatists -- didn't like his answers, he later told his family.

The men asked about his politics, his future plans, his views on the war. They checked his documents, took his fingerprints and stripped him to check if he had any nationalist tattoos or marks caused by wearing or carrying military equipment.

Russia is disappearing thousands of Ukrainians

“Evidence is mounting that Russian authorities are also reportedly detaining or disappearing thousands of Ukrainian civilians who do not pass ‘filtration’,” Blinken continued.

Mounting evidence of execustions

“There are reports that some individuals targeted for ‘filtration’ have been summarily executed,” Blinken added, “consistent with evidence of Russian atrocities committed in Bucha, Mariupol, and other locations in Ukraine.”

But how true are the Polish PM's accusations of concentration camps?

While all of this may sound worrying, it pales in comparison to what Russia has planned for the Ukrainians living in the four territories Vladimir Putin illegally annexed from Ukraine last year.

After months of bombing, Russia starts rebuilding Mariupol

The reconstruction plan, due for completion in 2035, aims to support the narrative that Moscow has saved the Russian-speaking population from Ukrainian discrimination

For 80 days between February and May, the Russian army besieged the city of Mariupol. Artillery and shelling leveled most of the buildings in this coastal city on the Azov Sea. Mariupol is a key hub linking the Crimea peninsula, which Russia illegally annexed in 2014, with eastern Ukraine’s Donetsk and Luhansk regions, a declared target of Putin’s invasion. In September 2022, Russia declared it was annexing the occupied territories, including Mariupol.

Ukrainian authorities say that during the Russian siege, at least 25,000 residents of this city died out of a pre-war population of 430,000. The United Nations has confirmed the deaths of about 1,350 residents, but admitted this is a partial count and that there are “probably thousands more dead.” Tens of thousands more fled or were sent out of Ukraine. About 90% of the buildings were damaged or razed by the attacks.

Now that the city is under its control, Russia has begun a reconstruction plan. In just six months, the Kremlin has built new homes in this destroyed city: a dozen apartment buildings with room for about 2,500 people now stand on Kuprina Street, southwest of the city. The following images, captured by the European Space Agency’s Sentinel-2 satellite, show how the land changes from a vacant lot in June to a residential complex in December.

Occupied Ukraine is getting 24 new "penal colonies"

On January 24th, while the world was worried about ensuring timely tank deliveries to Ukraine, Russian Prime Minister Mikhail Mishustin signed an order to set up 24 new penal colonies across Doentsk, Luhansk, Kherson, and Zaporizhia.

Russia's official decree

“The decree from the Russian government,” wrote Newsweek reporter Isabel Van Brugen, “shows that 12 penal colonies will be set up in the Donetsk region.”

Luhansk, Kherson, and Zaporizhzhia

Van Burgen added that “a further seven in the Luhansk region, three in the Russian-controlled part of the Kherson region, and an additional two facilities will be built in Zaporizhzhia, where a ‘settlement-type colony’ will also be established.”

A matter of symatics

While Russia may claim these new facilities will be penal colonies, it is quite clear they will be something wholly more sinister. Though the world once said never again, it appears as if we will see the mistakes of the twentieth century repeated in the twenty-first century.

Johnson says Putin threatened him with missile strike during phonecall before Ukraine invasion

BORIS JOHNSON HAS claimed that Vladimir Putin told him “I don’t want to hurt you, but with a missile, it would only take a minute”, in a call ahead of the Russian invasion of Ukraine.

Johnson, who would emerge as a vocal backer of Volodymyr Zelenskyy’s administration in the months after Russia invaded, made the claim in a new three-part series for BBC Two looking at how the West grappled with Putin in the years leading up to the war in Ukraine.

Talking about a phone call between the two leaders ahead of Moscow’s invasion of Ukraine, Johnson said: “He sort of threatened me at one point and said: ‘Boris, I don’t want to hurt you, but with a missile, it would only take a minute’, or something like that.”

But the Kremlin has disputed the claim, saying there were “no threats with missiles” during the bilateral conversation held in February 2022.

Kremlin spokesman Dmitry Peskov, asked about Johnson’s comments today, said that the British politician’s account was untrue, “or, more precisely, it was a lie”.

Peskov said the former Conservative Party leader may have deliberately lied or failed to understand what the Russian leader was telling him.

“There were no threats with missiles,” Peskov said during a conference call with reporters.

“While talking about security challenges to Russia, President Putin said that if Ukraine joins Nato, the potential deployment of US or other Nato missiles near our borders would mean that any such missile could reach Moscow in minutes.”

Johnson told the documentary producers that the “extraordinary” conversation took place last February after he had visited Kyiv in a last-ditch attempt to show Western support for Ukraine amid growing fears of a Russian assault.

War would break out only days later, with Russia launching its attack on Kyiv on 24 February.

Johnson said Putin had a “very relaxed tone” and an “air of detachment” as he spoke.

University years

Vladimir Putin graduated with a law in 1975 at Leningrad State University (nowadays St. Petersburg State University).

Mentor

While in university, Putin met assistant professor Anatoly Sobchak, who would later become his political mentor.

Secret agent man

The same year Putin graduated from university, he joined the KGB, the chief Soviet security agency.

There’s still controversy about what exactly were his responsibilities within the government entity.

Pictured: Former headquarters of the KGB, which currently serves as the offices of the FSB RF.

Stationed in East Germany

What is known is that Vladimir Putin lived in Dresden, then part of East Germany, from 1985 until 1990.

Pictured: Vladimir Putin and his parents in 1985, just before moving to East Germany.

Happily married

He married Lyudmila Shkrebneva in 1983, with whom he had at least two daughters. The couple officially divorced in 2014.

The fall

According to Time Magazine, during the fall of the Berlin Wall in November 1989, he saved the files from Dresden’s Soviet Culture Center and the KGB Villa and then burned the KGB files while handing over the rest to German authorities.

Leaving the KGB

According to Putin, he resigned from the KGB as a Lieutenant Colonel in the middle of the failed coup from Communist hardliners against the government of Mikhail Gorbachev.

Learning the ropes

Putin returned to St. Petersburg in 1990, where he worked at his alma mater. There, he renewed his friendship with Sobchak.

In this 1993 photo, Putin can be spotted behind Sobchak and Austrian politician Alois Mock during an official visit to the University of St. Petersburg library.

Rising star

Anatoly Sobchak became the first democratically-elected mayor of St. Petersburg in 1991. As head of the city government, he appoints Vladimir Putin as one of his deputies.

Here, Putin can be seen with Prince Charles during an official visit of The Prince of Wales to St. Petersburg in 1994.

The big leagues

After Sobchak lost the mayoral re-election in 1996, the young Putin, who had been his campaign manager, moved to Moscow to try his luck in federal-level politics.

The inner circle

Putin quickly ascended within the inner circle of Boris Yeltsin, occupying different high-ranking positions, including Director of the FSB RF, the successor of the KGB.

Law and order

The Russian people became acquainted with Putin as a “law-and-order” politician during the Second Chechen War, which allowed him to surpass his political rivals.

Acting president

On December 31, 1999, Boris Yeltsin unexpectedly resigned. Putin, who Yeltsin had hoped would succeed him as president of the Russian Federation, took over as acting president.

Unexpected demise

Putin asked Sobchak in February 2000 to help him in his presidential campaign, but his mentor unexpectedly died not long after meeting him.

Pictured: Putin in 2006, giving a speech at the opening of a monument in memory of Sobchak in St. Petersburg.

An end that is a beginning

Vladimir Vladimirovich Putin was elected President of the Russian Federation on March 26, 2000. Besides a one-term stint as Prime Minister, from 2008 to 2012, he has remained there ever since.

Will Putin's defeat lead to a bigger catastrophe?

Russia could collapse into several new states if President Vladimir Putin loses his war in Ukraine according to a top British economist.

Warning global leaders

Timothy Ash is warning global leaders that Russia’s collapse into a number of smaller states could be inevitable if the country is defeated by Ukrainian forces.

The world shouldn't take Russia's collapse lightly

A senior fellow of international relations at Chatham House in London, Ash published his warning in the Kyiv Post on January 21st and cautioned the war’s onlookers that they shouldn’t take the situation lightly.

The end of Putin

"I see a decent chance that we see the end of Putin and, while not my base case, I think it's possible we see a collapse of the Federation into many new states—as with the USSR in 1991," Ash wrote.

Russia isn't just one big state...

Russia isn’t a homogeneous state like some of its European neighbors. The Russian Federation is made up of a variety of republics, ethnicities, and autonomous administration zones, some of which are already keen to live under their own self-rule.

Russia can no longer win

Ash falls into a camp of experts that believes Russia no longer has a chance to win a decisive victory in Ukraine and this means its collapse is far more likely than earlier in the war.

No path to victory

“Russia has no path to victory,” Ash wrote, “and the longer the war goes on the worse it gets for Russia, and Putin.”

It's only a matter of time...

“It's only a matter of time really before either Russian forces in Ukraine collapse, or we see Moscow trying to sue for some kind of peace,” Ash added.

Suing for peace at a bad time

Unfortunately, if Putin tried to sue for peace now it would come at a time when fewer countries are willing to offer the Russian President the same sort of off-ramp that leaders like France’s Emmanuel Macron were calling for in June.

The West is more willing to fight

The United States and its Western allies have ramped up their military aid to Ukraine significantly and officials in Washington seem unwilling to entertain the possibility of letting Russia quit the war with concessions.

There is a moment of opportunity to defeat Russia

“We have a window of opportunity here, you know, between now and the spring when [the Ukranians] commence their operation, their counteroffensive,” Lloyd Austin said on January 20th while discussing his country’s new 2.5 billion dollar aid package for Ukraine.

Time is short

“That’s not a long time, and we have to pull together the right capabilities,” Austin continued.

Biden and NATO say no to Russia's concessions

On January 25th, the Biden administration and NATO officials told Russian authorities that they were no longer willing to make any concessions on the Kremlin’s main demands to resolve the conflict in Ukraine according to the Associated Press.

NATO will not close the door on Ukrainian membership

“In separate written responses delivered to the Russians, the U.S. and NATO held firm to the alliance’s open-door policy for membership,” wrote Vladimir Isachenkov and Mathew Lee.

NATO troops in Eastern Europe is non-negotiable

Isachenkov and Lee also noted that the U.S. and NATO “rejected a demand to permanently ban Ukraine from joining, and said allied deployments of troops and military equipment in Eastern Europe are non-negotiable.”

Defeat more likely with Western tanks on the way

All of this doesn’t bode well for the future of Russia if Timothy Ash’s predictions prove correct. A Russian defeat in Ukraine is even more likely now that Berlin and Washington have approved the sending of their main battle tanks to the embattled Ukranians.

Russia is likely to leave the conflict smaller than before

"Putin started this war to create a Greater Russia,” wrote Timothy Ash, “but the likely net effect will be a Lesser Russia."

Putin is desperate for soldiers: Russia is sending the seriously wounded back to war

Story by Zeleb.es

Injured troops sent back despite doctors orders

Seriously injured Russian soldiers are being sent back to fight on the frontlines in Ukraine without their doctor's permission according to a new Russian report.

The critically injured are being sent back

Citing information from Valentina Melnikova, the Executive Secretary of the Soldiers’ Mother’s Committee, Russian news outlet Agentstvo has reported that some critically injured soldiers are being sent back to war regardless of their injuries.

In some instances, soldiers who still had shell fragments in their bodies had been sent back to war while others who had been shot in the lungs were shipped back to Ukraine according to Agentstvo.

“According to the Soldiers’ Mothers Committee,” Agentstvo journalists wrote, “two servicemen who were treated for two months after sustaining serious lung wounds were told by their commanders that they would not be sent to a medical commission, but to a combat zone.”

The Agentstvo report went on to state that “several servicemen who received shrapnel wounds to their extremities were treated the same way, and the shrapnel was not removed.

“Also, ulcer patients and those who had had heart attacks or strokes before the war were returned to Ukraine after treatment,” the report added.

Valentina Melinikova isn’t the only person sounding the alarm about Russia’s treatment of its sick and injured soldiers.

Doctor's complaining about their patient's treatmentPrior to Agentstvo’s report, a member of the Presidential Human Rights Council spoke with a Russian news outlet about complaints from doctors in Moscow and Donetsk, angry that untreated patients were being sent back to war.

Olga Demicheva's comments

"We learned about the situation in which fighters who received high-tech medical care with recommendations for rehabilitation and treatment were immediately sent to the front instead of rehabilitation,” Olga Demicheva told RIA Novosti

“As a result, the treatments that they have undergone are just a waste,” Demicheva continued, “and instead of healthy people, we can get people disabled.”

“Doctors ask me to deal with the situation when untreated patients were sent to the unit instead of rehabilitation. This shouldn't happen," Demicheva added.

Russia’s reluctance to properly treat their wounded soldiers may indicate a growing lack of troops for their ongoing offensives in Ukraine.

Since the start of the war, the Ukrainian Armed Forces claimed to have eliminated 116,950 Russian soldiers according to an official Tweet on January 17th.

While Ukrainian figures for Russian losses cannot be independently verified, Western sources have agreed that Putin’s army has suffered at least 100,000 casualties.

“You are looking at well over 100,000 Russian soldiers killed and wounded,” General Mark Milley told a crowd at the Economic Club of New York in November 2022.

On January 17th, Vladimir Putin ordered that the Russian military increase its size to 1.5 million servicemen, almost certainly in reaction to his quagmire in Ukraine and the growing number of troops needed for the protracted war to come.

Putin is desperate for soldiers: Russia is sending the seriously wounded back to war (msn.com)

https://www.msn.com/en-ie/

Russia’s Wagner Group former commander who fled to Norway fears deportation,

Story by Zeleb.es

Russia’s Wagner Group former commander who fled to Norway fears deportation (msn.com)

https://www.msn.com/en-ie/

Apprehended by police in Norway

Andrey Medvedev, a former commander of Russia’s Wagner mercenary group who recently fled to Norway, has been apprehended by police and fears he will be deported to Russia, he told The Guardian.

Medvedev (pictured), crossed the border into Norway on January 13 and applied for asylum.

Photo: Newsrattler, YouTube