"Is Western Australia a democracy or a fascist state?" Andrew Mallard.

The extraordinary case of Andrew Mallard

"Is Western Australia a democracy or a fascist state?" ... Andrew Mallard.

"Why should these powerful people such as Kenneth Paul Bates, former senior DPP prosecutor, David John Caporn, former Assistant Western Australian Police Commissioner and others be above the law?" ... Andrew Mallard

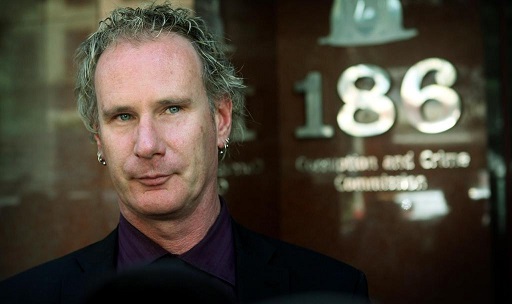

Andrew Mallard is a Western Australian who was wrongfully convicted of murder in 1995 and sentenced to life imprisonment. He was released from prison in 2006 after his conviction was quashed by the High Court of Australia.

https://lawonlineau.wordpress.com/2011/12/02/the-extraordinary-case-of-andrew-mallard/

Mallard v R [2005] HCA 68; (2005) 224 CLR 125; (2005) 222 ALR 236; (2005) 80 ALJR 160 (15 November 2005)

17 November 2005

http://www.austlii.edu.au/au/cases/cth/HCA/2005/68.html

ANDREW MARK MALLARD APPELLANT

AND

THE QUEEN RESPONDENT

"I was innocent and framed by former Red Lodge Freemason Western Australian Assistant Police Commissioner, David John Caporn and former Red Lodge Freemason Western Australian Senior DPP Prosecutor Kenneth Bates and others for the murder of Pamela Lawrence...."....Andrew Mallard

"I am determined that former WA Police Assistant Police Commissioner, David John Caporn, former senior DPP prosecutor, Kenneth Bates and others are eventually charged and prosecuted for a conspiracy to pervert the course of justice for framing me....".... Andrew Mallard

Australian Cases: Mallard (Andrew) v The Queen High Court December 2005

Mallard v The Queen [2005] HCA 68; (2005) 224 CLR 125; (2005) 222 ALR 236; (2005) 80 ALJR 160

15 November 2005 - High Court of Australia

http://netk.net.au/australia/Mallard.asp

Andrew Mallard's case: A timeline

1994: Perth jeweller Pamela Lawrence is brutally killed with a heavy instrument in her own store. The murder weapon has never been found

1995: Andrew Mallard is wrongly convicted of her murder

1996: Mallard's appeal to the Supreme Court of Western Australia is dismissed by Justices Kevin Park, Christine Wheeler and Justice Smith.

The books The Triumph of Truth (Who Is Watching The Watchers?) and other public information, as also show in the Film "The Law Lord".... "When It Is Important to Protect the Legal System of being exposed for corruption and wrongful activities, the carefully appointed Court Listings Manager is told to select Judges of Justices that the System knows will rule a certain way.... Justice Kevin Parker is well known and well exposed as a corrupted former Solicitor General of Western Australia, a former corrupted head of the Barristers Complaints Board, and a former Corrupted Supreme Court Justice ..... and Christine Wheeler was his personal assistant for years when Kevin Parker was the Solicitors General for Western Australia. and it was only a matter of the listing coordinator selecting a third Justice for Andrew Mallard's Supreme Court Appeal, who the System knew would Rule against Andrew Mallard winning his Full Supreme Court Appeal..

So John Quigley, the now Attorney General Of Western Australia was right when he said to Andrew Mallard..

"In Western Australia we have tired old judges who hardly have enough energy to pick up their pen to write the sentence of Life Imprisonment ... tried old judges who are too tired and lazy to properly scrutinize what the corrupt police and corrupt prosecution are about ... Andrew, you will only be released from prison and have your wrongful murder conviction quashed, if we can get your case to the High Court of Australia... because no judge in Western Australia will every have the balls to overturn your wrongful murder conviction, because to do so, would identify the whole of the Western Australian legal, police prosecution, court, and justice system as being inherently corrupt ... no judge in Western Australia will have the balls to do that .... Because Perth is too anal.... and the corrupted tentacles of the Western Australian legal, police prosecution, court, and justice system just wrap around your neck, and as you tear one of the corrupt tentacles of the Western Australian legal, police prosecution, court, and justice system off your neck, another corrupt tentacle just slithers around you .. one has no chance in fighting the corrupted Western Australian legal, police prosecution, court, and justice system, from within Western Australia ... to win against them and obtain any sort of justice, one has to go to the High Court of Australia,..".... WA Attorney General John Quigley

2003: After spending eight years of his sentence of life imprisonment in strict security, he petitioned for clemency

The Attorney-General for Western Australia referred the petition to the Court of Criminal Appeal, which later dismissed the appeal

2005: Mallard's appeal is heard in the High Court, his conviction is quashed

2006: After 12 years behind bars, Mallard is free

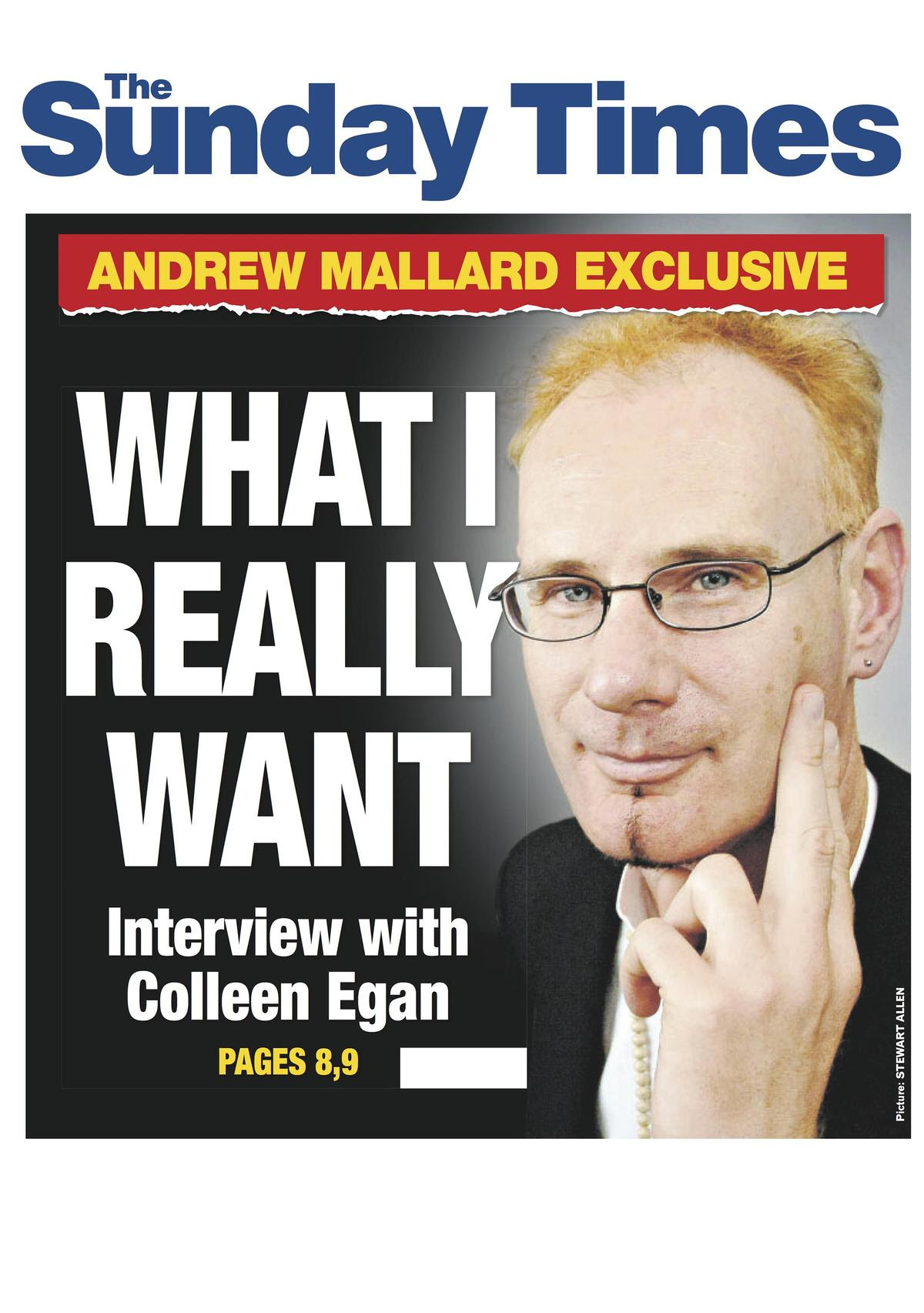

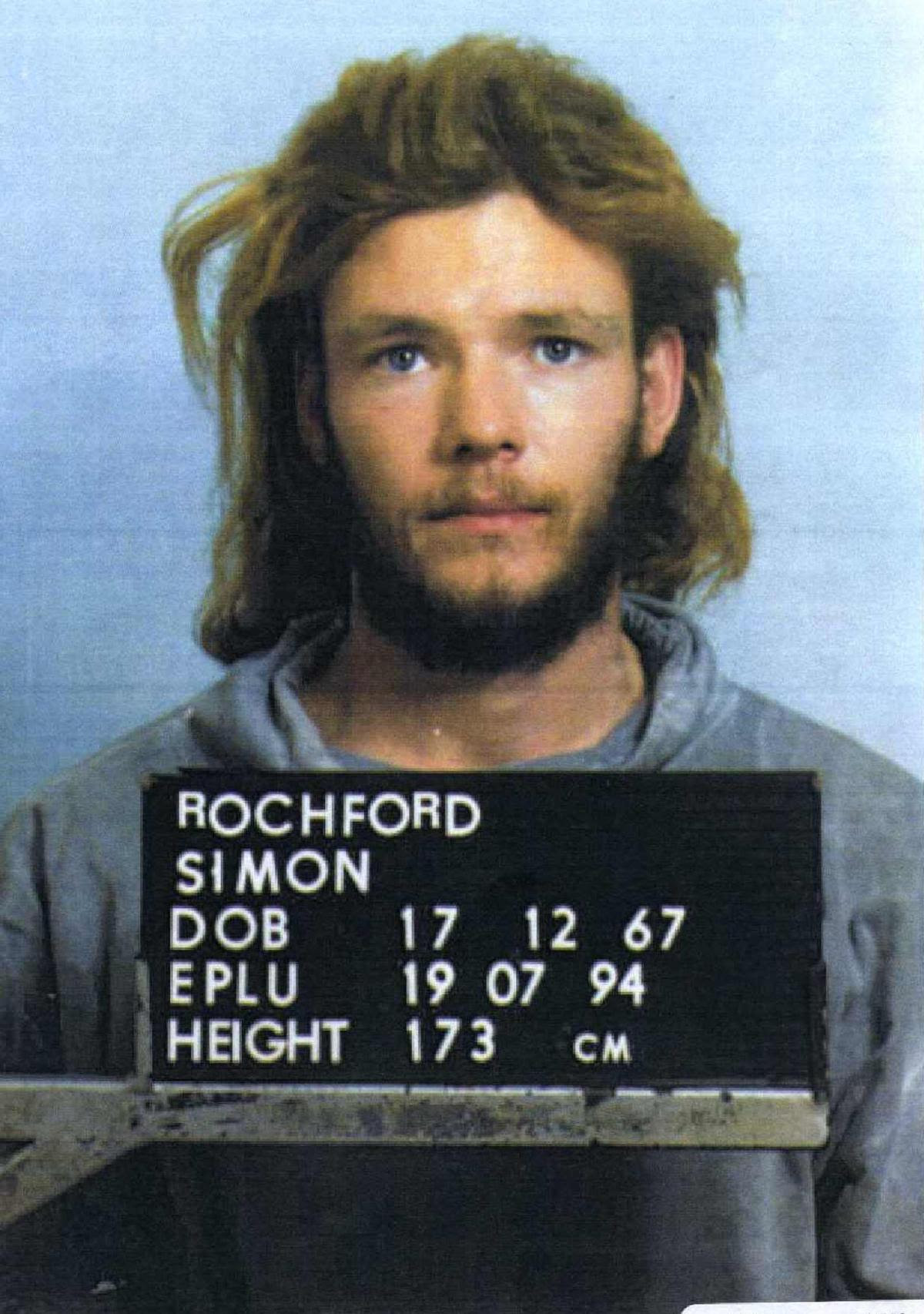

A cold case review is held and uncovers a partial palm print linking British backpacker and convicted murder Simon Rochford to the crime scene

A week after Rochford is questioned by police, he is found dead in his prison cell from suspected suicide

2007: A Corruption and Crime Commission investigation into the case leads to two assistant police commissioners, Mal Shervill and David Caporn, being forced to step down

2009: Mallard is granted a $3.25 million ex gratia payment for his time behind bars

2019: Mallard is killed in a tragic hit and run in Los Angeles

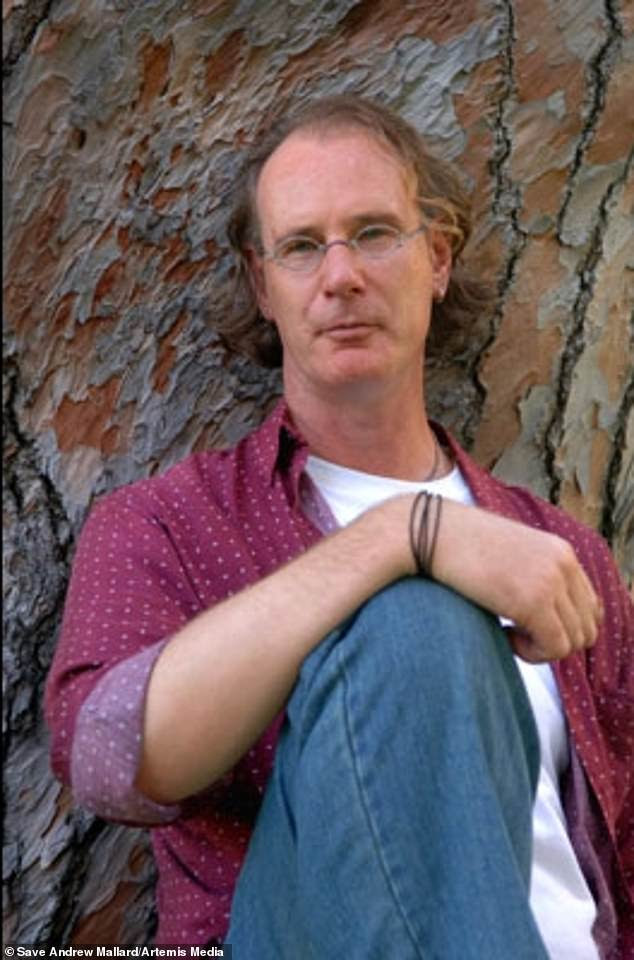

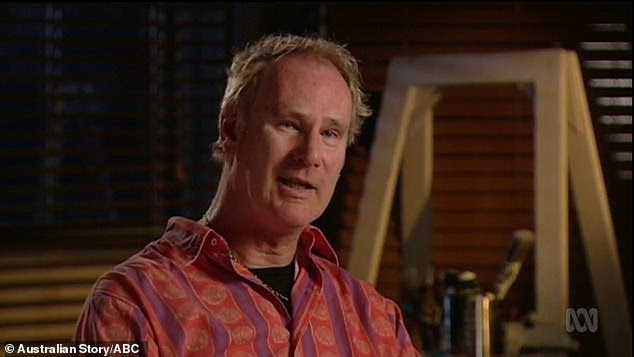

Andrew Mallard standing in front of one of his artworks in 2009. Credit- Lee Griffith

I was framed for murder, says Mallard

27 Sep 2010

https://www.abc.net.au/news/2010-09-27/i-was-framed-for-murder-says-mallard/2275496

The man wrongfully convicted of murdering West Australian woman Pamela Lawrence says he still suffers abuse from members of the public who think he is "some sort of psycho".

In 1995, Andrew Mallard was convicted of the brutal murder of the Perth wife and mother and sentenced to 20 years in jail.

He served 12 years in prison until the combined efforts of a journalist, politician and a team of high-profile, pro bono lawyers finally saw him exonerated.

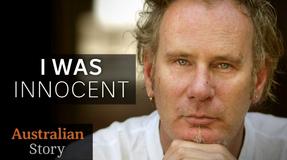

On ABC 1's Australian Story, Mallard speaks on camera for the first time, describing the circumstances leading up to his wrongful imprisonment and the torment he endured during his incarceration.

"I was wrongfully imprisoned. There's a stigma that goes with that and still goes with that," he tells the program.

"I know what they did to me and it's the truth. They framed me for a murder I did not commit."

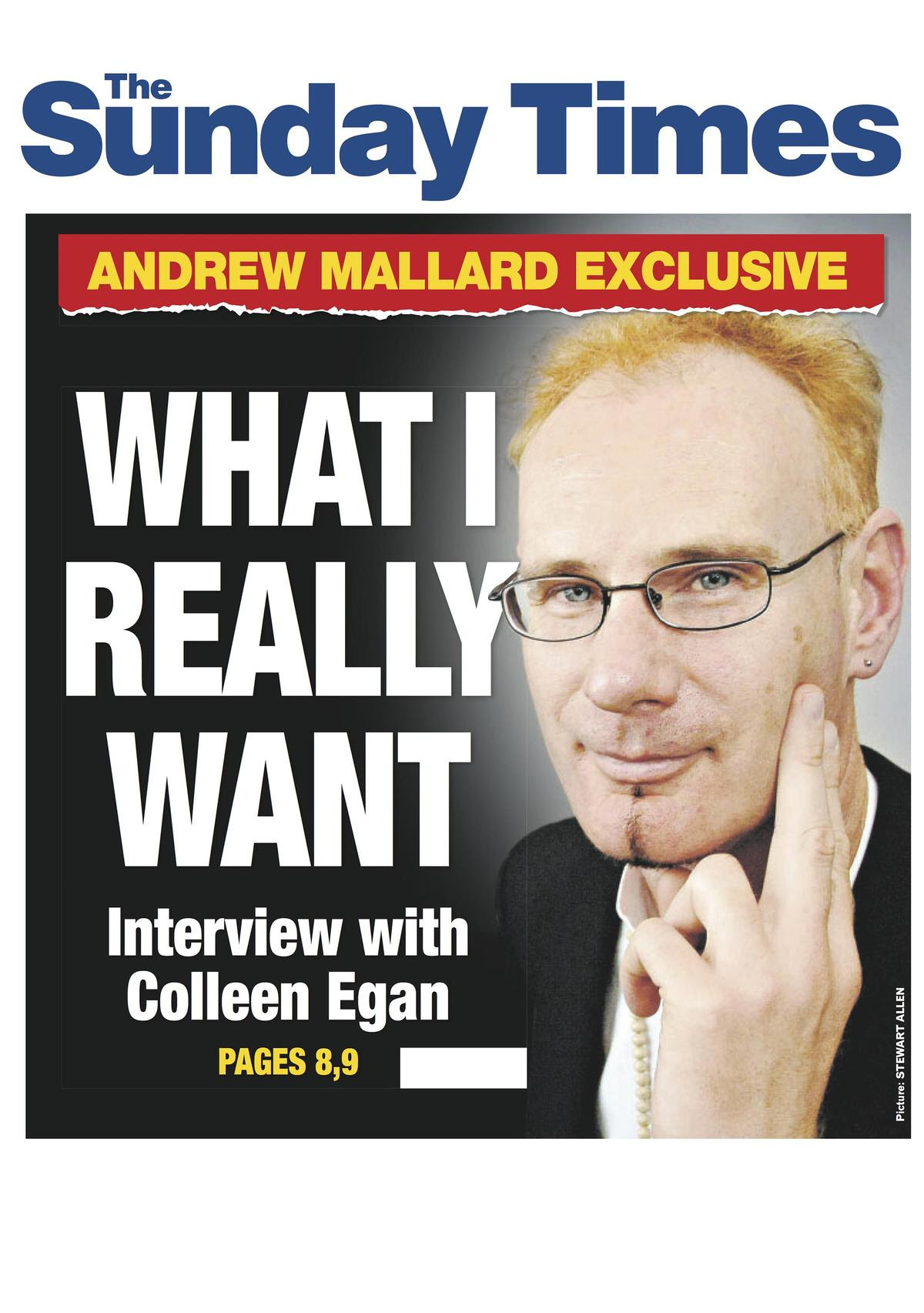

Journalist Colleen Egan had worked on the Mallard case for two years when she became convinced there had been a miscarriage of justice.

"There probably are still people out there who believe that Andrew did it. There probably always will be," Ms Egan said.

"It was just a cruel twist of fate that put him on a collision course with this inquiry and it was just a matter of fact that there were police who were willing to act dishonestly.

"There was a prosecutor willing to run a case that wasn't quite right, and there were three judges who refused to believe it when evidence was put in front of them, and they saw what the High Court saw."

Desperate in her efforts to find new evidence, she took a risk in seeking the assistance of shadow attorney-general John Quigley, who had been the WA Police Union's lawyer for 25 years.

Soon Mr Quigley, with his intimate knowledge of policing practices, made a breakthrough, finding crucial evidence never revealed to the defence.

"There was never a moment that I thought that this is too long or this is too hard," Mr Quigley said.

"I was by this stage driven by both anger and acute embarrassment - acute embarrassment of the legal profession and the judiciary in Perth, that I'd been part of this whole system for 30 years."

Mallard's supporters were devastated three years later when, despite the new evidence, a fresh appeal to the WA Supreme Court failed.

![]()

Andrew Mallard Endured 12years In Jail For A Murder He Did Not Commit Is Tragically Killed by USA Los Angeles Basketballer Kristopher Smith On Hollywood's Iconic Sunset Boulevard In A Car Hit And Run

Statement about the corrupt WA police, prosecution judicial and legal system on a documentary by E M Smith and WA Attorney General John Quigley

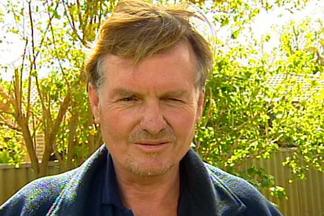

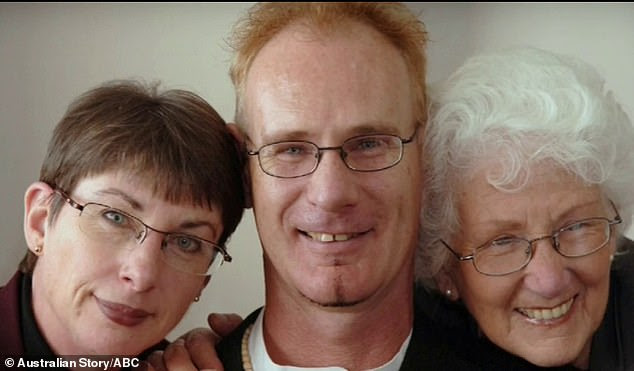

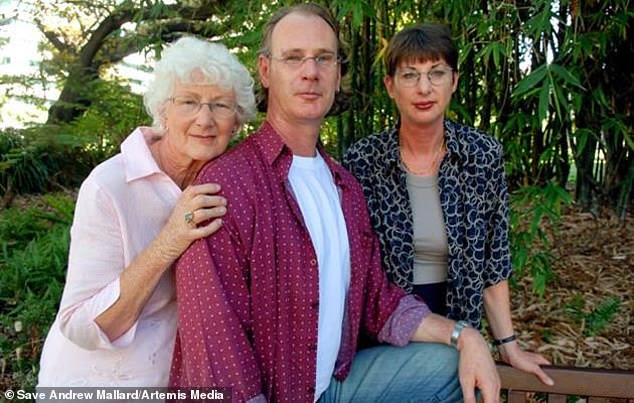

John Quigley (left) and Andrew Mallard

Andrew Mallard dead at 56 after hit-and-run in Los Angeles

EXCLUSIVE: Andrew Mallard, who spent 12 years in a WA jail after being wrongfully convicted of murder, has been killed in a hit-and-run crash in Los Angeles.

He had been living in the United Kingdom but regularly visited friends in the United States.

It is believed Mr Mallard was walking across a street in Hollywood about 1.30am local time Thursday when he was struck by a car.

The driver did not stop to help and despite efforts by a bystander to provide CPR until emergency services arrived Mr Mallard died at the scene, officers in LA say.

The 56-year-old was exonerated by the High Court in 2006 of wilfully murdering Mosman Park jeweller Pamela Lawrence in 1994.

He later received a $3.25 million settlement from the State Government.

Attorney-General John Quigley, who led the fight to clear Mr Mallard’s name, said today he was terribly saddened by the tragedy.

“It’s just fortunate that he got to spend 13 years of freedom after so much time wrongfully imprisoned,” he said.

Mr Mallard’s family are being assisted by the Australian consulate in the US.

On Friday afternoon, WA Police released a statement extending their condolences to Mr Mallard’s family.

“WA Police have been advised of the death of Mr Andrew Mallard in Los Angeles,” the spokesperson said.

“We have notified Mr Mallard’s family in Western Australia and we extend our condolences to them at this difficult time.”

Andrew Mallard Australian Man Wrongly Spent 12 Years Behind Bars For Murder then Killed by Los Angeles Basketballer, Kristopher Smith In Hollywood in A Hit And-Run Car Murder

US man , Los Angeles Basketballer Kristopher Smith IS Accused Of A Fatal Hit-Run Of Australian Andrew Mallard Faces Court On A Plea Deal

Los Angeles Basketballer Will Avoid A Long Prison Sentence After Pleading Guilty To The Fatal Hollywood Hit-and-run Death Of Australian Andrew Mallard

Los Angeles Basketballer, Kristopher Smith Pleaded Guilty To The Fatal Hit-run-Death Of Andrew Mallard

Andrew Mallard - Jailed for 12 years: Andrew Mallard's wrongful murder conviction - Australian Story

Andrew Mallard Documentary Part 2

"When I was 19 I became friends with a man named Andrew Mallard, who had just spent the past 12 years in prison. As I slowly unraveled the shocking elements of his story, I felt compelled to make this short documentary. Though in truth, there is so much that I left out due to the magnitude of the case and of the vast twists and turns that I discovered. It contains just a fraction of the full tangled -web of murders and conspiracies that I discovered whilst making it. In the future I hope to tell the full story - and to tell it better than I did... "... E.M. Smith

"I was wrongfully imprisoned. There's a stigma that goes with that and still goes with that," he tells the program.

"I know what they did to me and it's the truth. They framed me for a murder I did not commit."

Journalist Colleen Egan had worked on the Mallard case for two years when she became convinced there had been a miscarriage of justice.

"There probably are still people out there who believe that Andrew did it. There probably always will be," Ms Egan said.

"It was just a cruel twist of fate that put him on a collision course with this inquiry and it was just a matter of fact that there were police who were willing to act dishonestly.

"There was a prosecutor willing to run a case that wasn't quite right, and there were three judges who refused to believe it when evidence was put in front of them, and they saw what the High Court saw."

This is not the first or last time

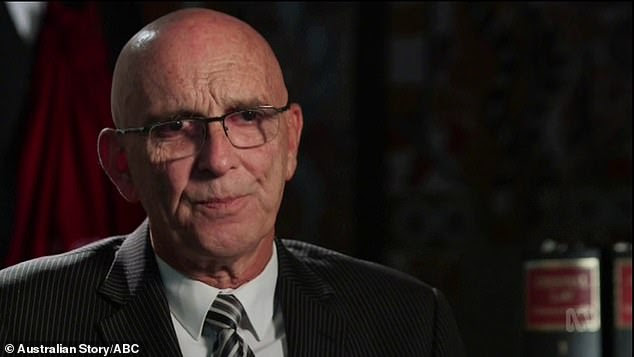

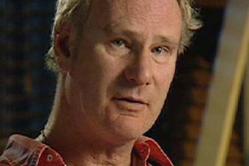

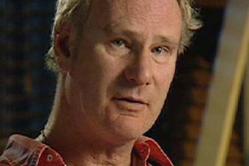

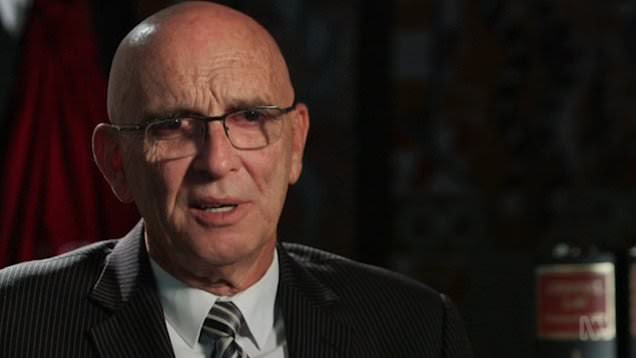

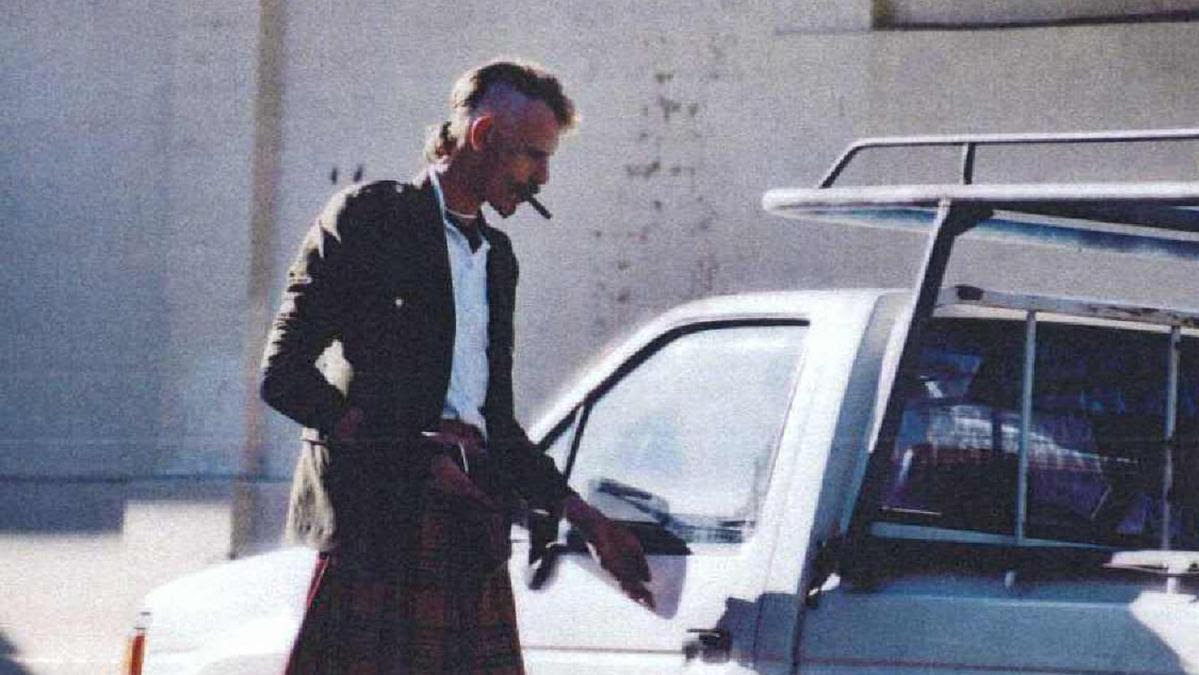

David John Caporn Red Lodge Freemason and the Former Western Australian Assistant Police Commissioner Who Helped DPP Prosecutor Frame Andrew Mallard for a Murder Andrew Did Not Commit.

As a a reward for helping to frame Andrew Mallard, David John Caporn Red Lodge Freemason and the Former Western Australian Assistant Police Commissioner, was given a new $100,000 a year job as the head the the WA Fire Service, a couple of days after he was forced to resign from the WA Police Force to stop a WA Police Force Internal Inquiry into his involvement is helped to frame Andrew Mallard for the murder of Pamela Lawrence.

This was not the first or last time David John Caporn the Former Western Australian Assistant Helped Try And Frame innocent people of crimes they did not commit, and help guilty Freemason Brothers not be charged for crime they did commit.

David John Caporn Red Lodge Freemason and the Former Western Australian Assistant Police Commissioner tried for year to frame a public servant and the mayor of Claremont for the Claremont Serial Killings.

David John Caporn Red Lodge Freemason and the Former Western Australian Assistant Police Commissioner helped well known Western Australian Footballer ,Barry Cable have sexual assault allegations dropped.

INL News Investigations indicate that David John Caporn Red Lodge Freemason and the Former Western Australian Assistant Police Commissioner and

REPORT ON THE INQUIRY INTO ALLEGED MISCONDUCT BY PUBLIC OFFICERS IN CONNECTION WITH THE INVESTIGATION OF THE MURDER OF MRS PAMELA LAWRENCE, THE PROSECUTION AND APPEALS OF MR ANDREW MARK MALLARD, AND OTHER RELATED MATTERS

7 October 2008

CORRUPTION AND CRIME COMMISSION

ISBN: 978 0 9805050 6 1

This report and further information about the Corruption and Crime Commission can be found on the Commission Website at www.ccc.wa.gov.au. Corruption and Crime Commission Postal Address PO Box 7667 Cloisters Square PERTH WA 6850 Telephone (08) 9215 4888 1800 809 000 (Toll Free for callers outside the Perth metropolitan area.) Facsimile (08) 9215 4884 Email This email address is being protected from spambots. You need JavaScript enabled to view it. Office Hours 8.30 a.m. to 5.00 p.m., Monday to Friday

CHAPTER FOURTEEN OPINIONS, RECOMMENDATIONS AND ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

14.1 Commission Opinions [707]

For the reasons stated previously in this Report, the Commission has formed the following opinions as to misconduct:

1. That Det Sgt Caporn engaged in misconduct within section 4(d)(ii) and (vi) of the CCC Act in that writing the letter to the Police Prosecutor dated 17 June 1994 containing errors and incorrect statements constituted the performance by him of his functions in a manner which was not honest or impartial and could constitute a disciplinary offence contrary to regulation 606(b) of the Police Force Regulations 1979, providing reasonable grounds for the termination of his employment as a public service officer under the PSM Act. [Refer paragraphs 327-337].

2. That Det Sgt Shervill engaged in misconduct within section 4(d) (ii) and (vi) of the CCC Act in that requesting Mr Lynch to delete from his report all reference to the salt water testing constituted the performance by him of his functions in a manner which was not impartial and could constitute a disciplinary offence contrary to regulation 605(1)(b) of the Police Force Regulations 1979, providing reasonable grounds for termination of his employment as a public service officer under the PSM Act. [Refer paragraphs 355-364].

3. That Det Sgt Shervill engaged in misconduct within section 4(d)(ii) and (vi) of the CCC Act in that causing the witnesses Katherine Barsden, Michelle Englehardt, Meziak Mouchmore, Katherine Purves and Lily Raine to alter their statements as they did without any reference in their final statements to their earlier recollections, involved the performance of his functions in a manner which was not honest or impartial and could constitute a disciplinary offence contrary to regulation 605(1)(b) of the Police Force Regulations 1979, providing reasonable grounds for termination of his employment as a public service officer under the PSM Act. [Refer paragraphs 365-442].

4. That Det Sgt Caporn engaged in misconduct within section 4(d)(ii) and (vi) of the CCC Act in that causing the witnesses Michelle Englehardt, Meziak Mouchmore, Katherine Purves and Lily Raine to alter their statements as they did without any reference in their final 164 statements to their earlier recollections, involved the performance of his functions in a manner which was not honest or impartial and could constitute a disciplinary offence contrary to regulation 605(1)(b) of the Police Force Regulations 1979, providing reasonable grounds for termination of his employment as a public service officer under the PSM Act. [Refer paragraphs 365-442].

5. That Det Sgt Shervill engaged in misconduct within section 4(d)(ii) and (vi) of the CCC Act in making false entries in the Running Sheets relating to the amendments to the statements of witnesses Katherine Barsden, Michelle Engelhardt, Meziak Mouchemore, and Katherine Purves involved the performance of his functions in a manner which was not honest and could constitute a disciplinary offence contrary to regulation 606(a) of the Police Force Regulations 1979, providing reasonable grounds for termination of his employment as a public service officer under the PSM Act. [Refer paragraphs 365-443].

6. That Det Sgt Shervill engaged in misconduct within section 4(d)(ii) and/or (iii) and (vi) of the CCC Act in that his failure to disclose to the DPP’s Office the prior statements of Katherine Barsden, Michelle Engelhardt, Meziak Mouchemore, Katherine Purves and Lily Raine, the original report of Bernard Lynch and details of the unsuccessful efforts by police to find a tool capable of inflicting the injuries suffered by Mrs Lawrence’s, involved the performance of his functions in a manner which was not honest or impartial and/or involved a breach of the trust placed in him by reason of his employment as a public officer and could constitute a disciplinary offence, contrary to regulation 603(1) of the Police Force Regulations 1979, providing reasonable grounds for termination of his employment as a public service officer under the PSM Act. [Refer paragraphs 463-480].

7. That Mr Kenneth Bates engaged in misconduct within section 4(d)(iii) and (vi) of the CCC Act in conducting the trial on the basis that the murder weapon was a wrench as drawn by the accused, but making no attempt to prove that such weapon could have caused the deceased’s injuries, particularly in circumstances where it was known that there was a problem about the pattern of some of the injuries, and involved a breach of the trust placed in him by reason of his employment as a public officer and could constitute a disciplinary 165 offence providing reasonable grounds for the termination of a person’s employment as a public service officer under the PSM Act. [Refer paragraphs 510-550].

8. That Mr Kenneth Bates engaged in misconduct within section 4(d)(iii) and (vi) of the CCC Act in that failing to disclose to the defence the results of the pig’s head testing of the wrench constituted or involved a breach of the trust placed in him by reason of his employment as a public officer and could constitute a disciplinary offence providing reasonable grounds for the termination of his employment as a public service officer under the PSM Act. [Refer paragraphs 485-490 and 543-550].

14.2 Recommendations

[708] The Commission makes the following recommendations:

1. That the Commissioner of Police give consideration to the taking of disciplinary action against Assistant Commissioner Malcolm William Shervill and Assistant Commissioner David John Caporn.

2. That the Director of Public Prosecutions gives consideration to the taking of disciplinary action against Mr Kenneth Paul Bates.

3. That consideration is given by the Commissioner of Police to making special provision for the interviewing by investigating police of mentally ill suspects.

4. That whenever there is legislation, fresh authoritative case law, or DPP guidelines which relate to the conduct of criminal investigation or the admissibility of evidence in such cases, senior police officers affected by such matters be required to attend formal seminars or meetings at which they can be made familiar with such matters.

5. That whenever the police obtain advice from the Office of the Director of Public Prosecution such advice be furnished in writing setting out, at least, the material considered, the opinion and the grounds upon which such opinion is based; or in cases of urgency, a detailed contemporary note should be made, preferably by the DPP officer or his secretary, and also by the police, setting out the matters specified.

6. That Mr Andrew Mallard gives consideration to raising a complaint with the Legal Practitioners Complaints Committee (LPCC) regarding the conduct of the trial by Mr Kenneth Bates. 166 (Division 3 of the Legal Practice Act 2003 deals with complaints made about legal practitioners. Section 175(2) specifies who can make a complaint to the LPCC including the Attorney General, the Legal Practice Board, the Executive Director of the Law Society, any legal practitioner or any other person who has had a direct personal interest in the matter.)

14.3 Acknowledgements [709]

Before concluding the Report it is desirable and proper for the Commission to acknowledge and pay tribute to the efforts of those who believed in the innocence of Andrew Mallard and who by their time and efforts secured his freedom and ultimate vindication. Those persons whose efforts were particularly significant were Ms Colleen Egan, journalist, Mr John Quigley MLA, Mr Malcolm McCusker QC, and Clayton Utz solicitors, who all acted without remuneration. Without their respective efforts and expertise, Andrew Mallard would still be in prison, convicted of a wilful murder he did not commit.

Police staked out Lance Williams' house for more than a year-ABC News

Reporters converge on Lance Williams' parents' house in Cottesloe, seeking interviews in relation to false trumped up allegations by David John Caporn the the head of the Macro Task Force that Lance Williams was the Claremont Serial Killer-ABC News

The then lord Mayor of Claremont, Peter Weygers' Claremont home was searched by police in relation to false trumped up allegations by David John Caporn the the head of the Macro Task Force that Peter Weygers' was the Claremont Serial Killer-ABC News

Taxi driver Steven Ross was questioned by police investigating the Claremont Serial Murders, in relation to false trumped up allegations by David John Caporn the the head of the Macro Task Force that Taxi driver Steven Ross was involved in the Claremont Serial Killings. ABC News

What was Andrew Mallard accused of doing and how did he prove his innocence?

John Quigley (left) Western Australian Attorney General and Andrew Mallard

Michael Kirby says he would support a body to review criminal cases where there are allegations of miscarriage of justice-ABC News

There can not no doubt that former Assistant Western Australian Police Commissioner David John Caporn has already been exposed by public evidence that former Assistant Western Australian Police Commissioner David John Caporn was a corrupt police officer who abused his position as a police officer … There is also the matter of former Assistant Western Australian Police Commissioner David John Caporn being accused of being involved in the stopping of the investigations in the allegations of sexual abuse of a young girl …. against well known Perth, footballer, Barry Cable ….

It seems clear that former Assistant Western Australian Police Commissioner David John Caporn has been given the Green Light to be involved in any criminal behaviour without fear of criminal investigation against former Assistant Western Australian Police Commissioner David John Caporn and without fear of being charged with any criminal offense… there is a lot more the NYT CSK Investigation Team can say about the criminal activities of former Assistant Western Australian Police Commissioner David John Caporn which will be brought up in due course ….

“To win Andrew Mallard’s High Court appeal would have to expose serious police corruption and that the police do everything to cover their tracks of corrupt behaviour and that if I helped Andrew Mallard to expose serious police corruption that these corrupt Western Australian Police would go for my gutz…” ….. John Quigley, the Attorney General For Western Australia …

“ I have just seen a gross case of injustice against Andrew Mallard where three Supreme Court Judges refused Andrew Mallard’s Full Court Appeal which was based on the fact that material evidence has been held back by the police …

The appeal went on for 26 hearing days … which was unheard of… normally appeals will be heard over or two days at the most … so the three appeal judges got to hear everything .. the appeal was very well presented by Malcolm McCusker and his team … and all three judges at the end went on to say no ... "we dismiss the appeal "…

I walked out of that court and thought that I must be the biggest idiot on the planet I have just seen a gross case of injustice against Andrew Mallard where three Supreme Court Judges refused Andrew Mallard’s Full Court Appeal that should have led to a retrial … and all three judges say no …”

“.. We had a person who was infirm … not insane by infirm … who had been picked upon by a group of very powerful and very dishonest police officers, who had been thrown in jail for the rest of his (Andrew Mallard’s) life .. and lazy old judges bearly with enough energy to lift their fountain pen to write the sentence “Life Imprisonment” frail of judges who were too lazy to properly scrutinize what the police were about … so I said to Andrew .. I actually help Andrew in my arms in prison because no one else could get in there … and Andrew was very very scared at that time he was 10 years into his 20-25 or 30 years that he had to do in prison … he was very frail at that point … so I held Andrew in my arms at that point and promised that so matter how long it took that I would never leave his side … never.. Andrew asked me if he would ever get out of prison … I replied …well only if we got this case back over to the High Court in Canberra … because although we would first have to appeal to Western Australian judges there would be no Western Australian Court that would overturn his conviction … because the consequences of doing so would be to identify the whole of the Western Australian Police, prosecution and court system as being corrupt … and no Western Australian Judge would have the balls to say that … because Perth is too anal and the tentacles of the system just get tangled around your throat … as you tear one corrupt tentacle off another one slithers around you … and have just got no chance …

"...We are all product of the experience we go through . we grow through our suffering .. for example, we grow through the experience of watching our father die … so what I am trying to say is that through this suffering we often grow into the better person .. and I am sure that through Andrew’s suffering that Andrew grew into something bigger and better … ” … Attorney General for Western Australia, John Quigley…

Andrew Mallard Set up of a false murder charge by the former Assistant Western Australian Police Commissioner David John Caporn and senior Western Australian Director of Public Prosecutions prosecutor Kenneth Paul Bates and other police officers and the Director of Public Prosecutions for Western Australia

I was wrongfully imprisoned .. there is a stigma that goes with that ,., and still goes with that … I still get abuse from certain members of the public …. I still get scoffed at etc. …. people don’t know the full story ….. they think I am some sort of psycho … some sort of mentally ill patient … I had done nothing wrong .. I was innocent and I protested my innocence from the word go .. for nearly 12 years I was protesting my innocence constantly and continually because it was the truth …

He would tell me that he never resolved his anger … he was always angry about the police and the prosecutors that brought the injustice .. Andrew was probably not for this planet .. the bad luck that Andrew had … he was not a soul that belonged here in some ways…

The Greeks talk about the Goddess Clotho would spin people’s fate .. Clotho was spinning against Andrew from the Get Go …

This whole story is like some Greek Tragedy … the audience thinks it’s all going well … but it all turns to mud …

Perth, 24th May 1994

Pamela Lawrence was violently murdered by someone else other than Andrew Mallard… who was deliberately set up to be wrongfully charged and wrongfully prosecuted by Freemason Police Officers and prosecutors, which included the former Assistant Western Australian Police Commissioner David John Caporn and senior WA DPP prosecutor Kenneth Paul Bates who Andrew Mallard supported by the ruling of the High Court and the Western Australian Corruption Commission … deliberately produced misleading evidence and withheld material evidence at Andrew Mallard’s murder trial which Andrew Mallard has always publicly claimed was … “… a serious criminal conspiracy to pervert the course of justice committed by former Assistant Western Australian Police Commissioner David John Caporn and senior WA DPP prosecutor Kenneth Paul Bates ……. and they should have been arrested and prosecuted for such a serious crime …. why are they allowed to get away with such criminal behaviour which destroyed and my family’s life ?…”

“.. we found that a lot of the information Andrew provided in the video interview with the police was information fed to him by the undercover officer Gary … and fed to him by the detectives that were interviewing Andrew …”

“.. a report that had said they had done a test on a pigs head .. which showed that a wrench could not have inflicted those injuries of Pamela Lawrence … while all the while the prosecutor had marked and read and deliberately kept this information from the court .. this was something that a lawyer should never ever do ….” … Attorney General for Western Australia, John Quigley…

“... over the course of my life, I had suffered from a behavioral situation where I would acquiesce … I would try to please people …”.. Andrew Mallard

“... and in fact that in the statement of facts to the prosecution certain police officers state their concerns that they did not think that I was the murdered anyway ….it’s in the statement of facts to the prosecution ”… Andrew Mallard

“... I have 3-4 years of psychotherapy to deal with post-dramatic stress .. for someone that has been found innocent after they have been wrongfully convicted there is no provision in the system for that .. you ate just spat out … you are spat out …. put are just spat out by the Belly of the Beast …. so to speak …. when I was first released … I used to have serious panic attacks … you have to remember I was still the prime suspect and thus people would give me a wide birth anyway … I hope that I am able to change things in the police and justice system .."...I never believed that I was incarcerated for the rest of my life, simply because I was innocent. ....

Guys wearing suits came dashing across the road to me pulled me out of my seat and threw me over the bonnet of the car … handcuffed me and finally shoved me into the back seat of a police car … a detective sat either side of me on the back seat of the police car, then my head was violently pushed between my knees, and the next time I hear is the cocking of a weapon ... which I recognized as a gun from the time I spent in the army and a pistol was shoved into my face … "..... words spoken by Andrew Mallard.

"... I was determined to stay forward .... keep my head forward and keep going forward ... and I did that ,,,, " words spoken by Andrew Mallard.

“ … I hope that I am able to change things in the police and justice system .." .... I don't believe that there is an infallible justice system or an infallible police service because you are dealing with people .... and people make mistakes and people can be bad as I just said .. lawyers and police not only have a legal duty but also a moral duty to us the public and that is a very very difficult job and position to be in … so I have great profound respect for the police service and the justice system and lawyers as a whole, but it is the people factor that always throws a wrench into the system … , " words spoken by Andrew Mallard.

“...We tend to be brought up that the police and the justice system is just .. we have a justice system that carries out the law .. but I have serious doubts that the justice system is entirely just …”

What was Andrew Mallard accused of doing and how did he prove his innocence?

"I was Innocent"....Andrew Mallard - Australian Story

Andrew Mallard: Wrongfully jailed for 12 years

Andrew Mallard's wrongful murder conviction

"...I never believed that I was incarcerated for the rest of my life, simply because I was innocent. ... the detectives sat either side of me on the back seat of the police car, then my head was violently pushed between my knees, and the next time I hear is the coking of a weapon ... "..... words spoken by Andrew Mallard.

"... I was determined to stay forward ... keep my head forward and keep going forward ... and I did that ,,,, " words spoken by Andrew Mallard.

" .... I don't believe that there is an infallible justice system or an infallible police service because you are dealing with people .... and people make mistakes ... " words spoken by Andrew Mallard.

"... I never look at the experience that I suffered as a negative thing ... it made me a better person for it ...

Andrew Mallard sat for 12 years behind bars and become the subject of documentaries and legal fights until his wrongful conviction was overturned and Andrew Mallard was set free in 2006 .... this documentary the unmaking of a Murdered was released a couple of years later ...

Andrew Mallard spoke with Anne with his love of art and his desire to have a family ... his family says that it was that desire that brought Andrew Mallard to Los Angeles ... Andrew mallard came to Los Angeles this week to visit his fiance,... but while walking across Sunset Strip Boulevard in Los Angeles, but Andrew Mallard was struck and killed by a car yesterday morning ... not Andrew Mallard's family are on the fight for justice .. the driver of the car didn't stop and LAP Police are still trying to find that person ... Andrew Mallard's sister in Australia has told the media in Australia that ..." they're heartbroken to have lost Andrew twice ..."

But those who know Andrew Mallars say that his ability to forgive will be his legacy and a lesson for us all .....

Right now police are looking for any information as to who killed Andrew Mallard .... again it happened here on Sunset Boulevard early Thursday morning ... they don't have a description of the car or the driver, but they are hoping that so much video footage and businesses here that something will lead the police to Andrew Mallard's killer

Andrew Mallard was wrongfully imprisoned for the murder of Perth woman Pamela Lawrence-Australian Story

Update:

Since this article was written a man has been arrested for the hit and run death of Andrew Mallard in Hollywood, Los Angeles, USA,

Teenager charged over Andrew Mallard's hit-and-run death in Los Angeles

By Madeline Palmer

Teenager charged over Andrew Mallard's hit-and-run death in Los Angeles

By Madeline Palmer

24 Apr 2019

https://www.abc.net.au/news/2019-04-24/teenager-charged-over-andrew-mallard-hit-and-run-death-in-us/11044648

Teenager charged over Andrew Mallard's hit-and-run death in Los Angeles

By Madeline Palmer

How was Andrew Mallard cleared?

Key points:

Andrew Mallard was run over on Sunset Boulevard in Hollywood

He had started a new life and was visiting his fiance at the time

Mr Mallard's family were informed by DFAT of the arrest

Andrew Mallard spent 12 years in jail for the murder of Pamela Lawrence — a crime he didn't commit. Here's how he was freed.

PHOTO: Andrew Mallard was wrongfully imprisoned for the murder of Perth woman Pamela Lawrence. (Australian Story)

PHOTO: Mr Mallard spent 12 years in jail until he was exonerated. (ABC News)

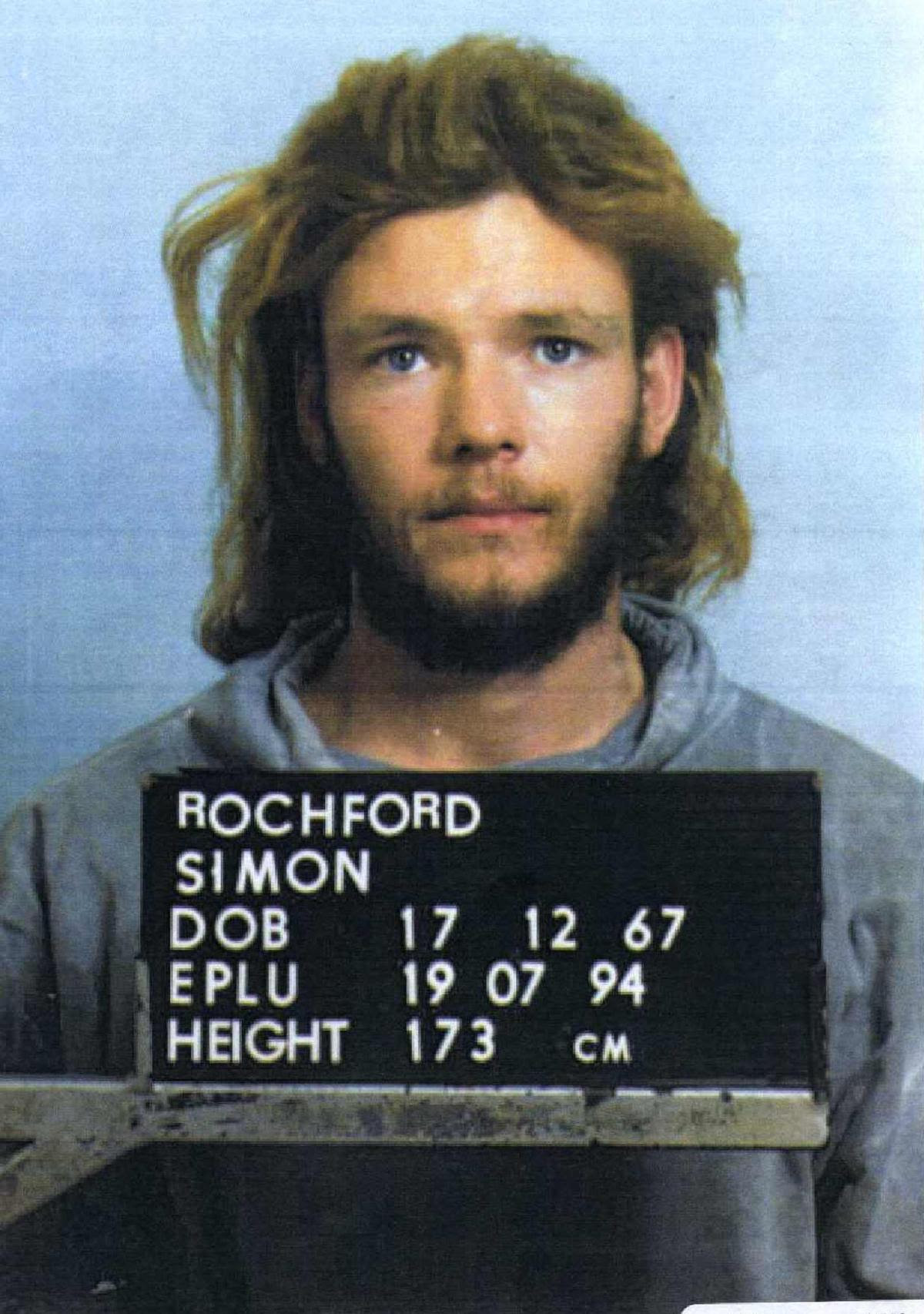

A 19-year-old man has been arrested in the US in relation to the hit-and-run death of Perth man Andrew Mallard, who spent 12 years in jail after being wrongfully convicted of murder.

Mr Mallard died after being stuck by a moving vehicle while crossing a road in Los Angeles last week.

He was hit by a car on the iconic Sunset Boulevard in Hollywood after leaving a bar late on Thursday night and could not be revived.

Mr Mallard had been visiting his fiancee during a trip from his new home in Britain, where he moved after being exonerated in 2006.

The LA Police Department had offered a $US25,000 ($35,000) reward for information into the incident.

US media outlet KTLA5 reported Kristopher Ryan Smith was charged with a felony hit-and-run after turning himself into police on Tuesday.

According to the LA County Sheriff's Department, Mr Smith was released on $US50,000 bail the evening of his arrest.

He is due to appear in the Los Angeles Municipal Court Traffic Division on May 14.

Mr Mallard's family confirmed they were informed of the arrest by the Department of Foreign Affairs and Trade.

Mallard wrongfully imprisoned for murder

Mr Mallard was convicted of the brutal murder of Perth wife and mother Pamela Lawrence in 1995 and was sentenced to 20 years.

Ms Lawrence was bludgeoned to the head in broad daylight on the afternoon of Monday May 23, 1994, at her jewellery shop Flora Metallica in the upmarket Perth suburb of Mosman Park.

She died hours later in hospital.

Mr Mallard was arrested for murder after several interviews with police, where he speculated how Ms Lawrence may have been killed and drew a picture of a wrench which police said he used to kill her.

Mr Mallard said he was fed information by police to repeat back to them, but police treated it as a confession and he was sentenced to 20 years' jail.

He served 12 years in jail until the combined efforts of a journalist, a politician and a team of high-profile, pro bono lawyers finally saw him exonerated.

Police later admitted Mr Mallard wasn't responsible for the crime after a cold case review of Ms Lawrence's murder found shavings of blue paint recovered from her head linked the crime to murderer Simon Rochford.

Living in Perth had become 'untenable'

After receiving a record $3.25 million compensation payout from the West Australian government, Mr Mallard graduated from university with a degree in fine art and travelled to London to start a masters.

He told the ABC's Australian Story that living in Perth had become "untenable", as members of the public still treated him as if he was a murderer.

Mr Mallard was still based in the UK and frequently travelled to the US, where his fiancee lived, prior to his death.

A Corruption and Crime Commission inquiry was held into the alleged misconduct by police officers in the case, but the officers involved resigned after a police inquiry began, avoiding the disciplinary process.

Topics: death, community-and-society, law-crime-and-justice, wa, perth-6000, united-states

John Quigley (left) and Andrew Mallard

John Quigley (left) was instrumental in getting Mr Mallard's murder conviction quashed. (ABC News)

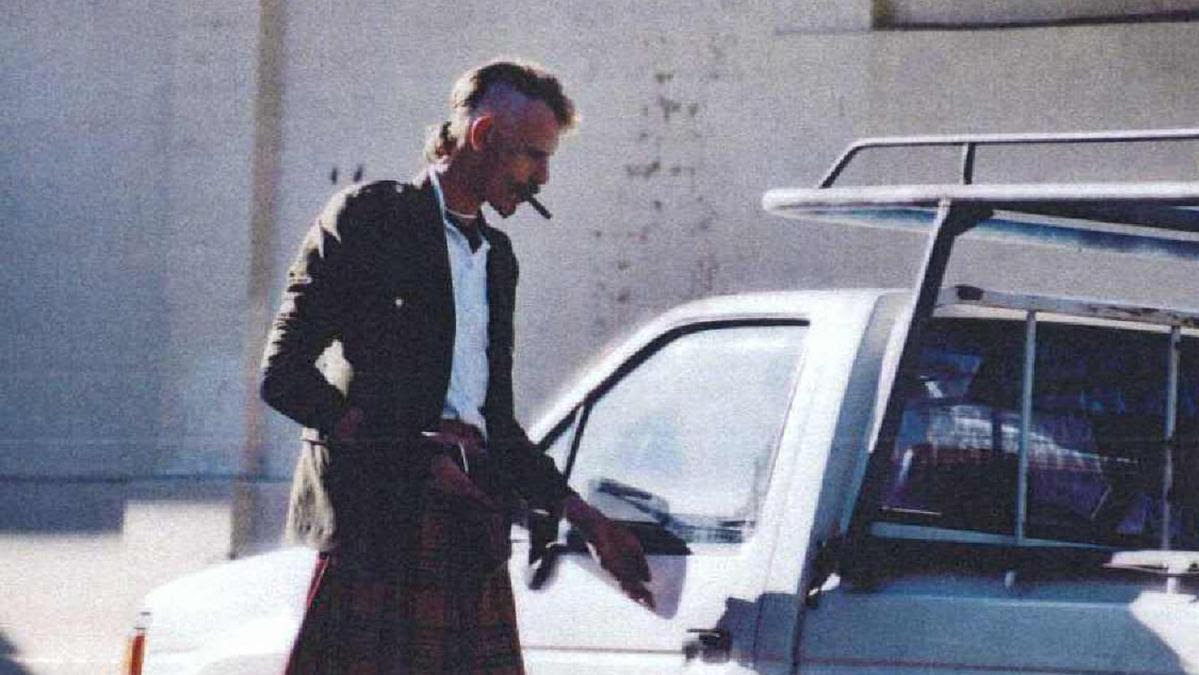

Colleen Egan@ColleenEgan1

On the day we walked from Casuarina prison...

Colleen Egan Chief of Staff to John Quigley Attorney General of Western Australia

https://www.businessnews.com.au/Person/Colleen-Egan

"Colleen Egan - Wikipedia" https://en.m.wikipedia.org/

Colleen Egan

Colleen Egan was an Assistant Editor at The West Australian newspaper. She played a role in obtaining the acquittal of Andrew Mallard, a Western Australian man who had been wrongfully convicted of murder. She also unwittingly contributed to the political downfall of Western Australian Liberal

History

Egan, who has principally been employed as a print journalist by The Sunday Times, first established herself as an investigative journalist in 2000 when her exclusive interviews with terrorist Jack Roche were published in The Australian.[2] Her work has since taken her to London, covering trials at the Old Bailey, and back to Perth as a weekly columnist for The Sunday Times. She is now Chief of Staff for WA Attorney General John Quigley.

Egan was approached in 1998 by the family of Andrew Mallard who had been convicted and detained in 1995 for the murder of jeweller Pamela Lawrence. Her subsequent investigations revealed that Mallard's conviction had been largely based on a forced confession. Her book on the case, Murderer No More: Andrew Mallard and the Epic Fight that Proved his Innocence, was published by Allen & Unwin in June 2010.[3]

Awards

- Walkley Award for Most Outstanding Contribution to Journalism for 2006 for her role in the acquittal of Andrew Mallard.

- News Limited's 2007 Sir Keith Murdoch Award for Journalism, also for the eight-year investigation that led to the acquittal of Andrew Mallard.

- 2011, Davitt Award for Murderer No More

See also

References

- ^ ABC Radio National's Media Report programme of Thursday, 10 August 1995 and from Crikey (crikey.com.au) on Thursday, 12 June 2008 - A Crikey list: MPs Behaving Badly Archived 14 June 2008 at the Wayback Machine.

- ^ "Article from Sydney Morning Herald website, dated 27 November 2002". The Sydney Morning Herald. 27 November 2002. Retrieved 17 June 2008.

- ^ "Murderer No More: Andrew Mallard and the Epic Fight that Proved his Innocence" by Colleen Egan, published by Allen & Unwin in June 2010.

External links

- Transcript from Radio National Media Report programme, featuring interview with Colleen Egan (Broadcast on Thursday, 10 August 1995).

- Walkley Awards website page for Colleen Egan

Andrew Mallard, a free innocent man, wore Buddhist beads. May he find a next life that is kinder. RIP

12:02 PM - Apr 19, 2019

Andrew Mallard, wrongfully jailed for 12 years over WA murder, killed in hit-and-run crash in US

By Herlyn Kaur and staff

20 Apr 2019,

https://www.abc.net.au/news/2019-04-20/andrew-mallard-killed-in-hit-and-run-in-los-angeles/11032672

PHOTO: Andrew Mallard was wrongfully imprisoned for the murder of Perth woman Pamela Lawrence. (Australian Story)

RELATED STORY: When a murder confession is a con

RELATED STORY: I was framed for murder, says Mallard

A West Australian man who was wrongfully jailed for more than a decade has been killed in a hit-and-run crash in the United States.

Key points:

Andrew Mallard's family say they are devastated by his sudden death

Mr Mallard was convicted of the brutal murder of Pamela Lawrence in 1995

After 12 years in jail, a journalist, politician and pro-bono lawyers helped free him

WA Police have confirmed 56-year-old Andrew Mallard died in Los Angeles.

Mr Mallard was convicted of the brutal murder of Perth wife and mother Pamela Lawrence in 1995 and was sentenced to 20 years in prison.

He served 12 years in jail until the combined efforts of a journalist, politician and a team of high-profile, pro bono lawyers finally saw him exonerated.

In a statement, the family of Andrew Mallard said they were shocked to learn overnight of his sudden death.

Former journalist Colleen Egan, who played a role in obtaining the acquittal of Mr Mallard, said she was assisting the family with media queries.

"His mother, Grace Mallard, sister Jacqui and brother-in-law Wayne are all devastated by the news," she said in a statement.

"They are being assisted by the Australian consulate in the US."

The statement said Mr Mallard had been based in the UK and was travelling frequently to the US, where his fiancee lived, and was looking forward to getting married.

Family, friends mourn death

His sister Jacqui Mallard said the family was devastated his life was cut short.

"Those years were taken from him and now his life has been taken," she said.

In a statement, WA Attorney-General John Quigley told the ABC he was terribly saddened by the tragedy.

PHOTO: John Quigley (left) was instrumental in getting Mr Mallard's murder conviction quashed.

(ABC News)

After 12 years in jail, a journalist, politician and pro-bono lawyers helped free him

WA Police have confirmed 56-year-old Andrew Mallard died in Los Angeles.

Mr Mallard was convicted of the brutal murder of Perth wife and mother Pamela Lawrence in 1995 and was sentenced to 20 years in prison.

He served 12 years in jail until the combined efforts of a journalist, politician and a team of high-profile, pro bono lawyers finally saw him exonerated.

In a statement, the family of Andrew Mallard said they were shocked to learn overnight of his sudden death.

Former journalist Colleen Egan, who played a role in obtaining the acquittal of Mr Mallard, said she was assisting the family with media queries.

"His mother, Grace Mallard, sister Jacqui and brother-in-law Wayne are all devastated by the news," she said in a statement.

"They are being assisted by the Australian consulate in the US."

The statement said Mr Mallard had been based in the UK and was travelling frequently to the US, where his fiancee lived, and was looking forward to getting married.

Family, friends mourn death

His sister Jacqui Mallard said the family was devastated his life was cut short.

"Those years were taken from him and now his life has been taken," she said.

In a statement, WA Attorney-General John Quigley told the ABC he was terribly saddened by the tragedy.

"It's just fortunate that he got to spend 13 years of freedom after so much time wrongfully imprisoned," Mr Quigley said.

"My thoughts are with Grace and Jacqui."

Los Angeles Police are investigating.

'They framed me for a murder I did not commit'

Mr Mallard spoke to ABC's Australian Story in 2010, describing the torment he endured during his incarceration.

"I was wrongfully imprisoned. There's a stigma that goes with that and still goes with that," he said.

"I know what they did to me and it's the truth. They framed me for a murder I did not commit."

Ms Egan had worked on the Mallard case for two years when she became convinced there had been a miscarriage of justice.

"There probably are still people out there who believe that Andrew did it. There probably always will be," Ms Egan said.

"It was just a cruel twist of fate that put him on a collision course with this inquiry and it was just a matter of fact that there were police who were willing to act dishonestly.

"There was a prosecutor willing to run a case that wasn't quite right, and there were three judges who refused to believe it when evidence was put in front of them, and they saw what the High Court saw."

Desperate in her efforts to find new evidence, she took a risk in seeking the assistance of then shadow attorney-general John Quigley, who had been the WA Police Union's lawyer for 25 years.

Soon Mr Quigley, with his intimate knowledge of policing practices, made a breakthrough, finding crucial evidence never revealed to the defence.

Mr Mallard's supporters were devastated three years later when, despite the new evidence, a fresh appeal to the WA Supreme Court failed. But they fought on.

It would be another two years before Mr Mallard's conviction was quashed by the High Court amid allegations of police and prosecution misconduct.

Topics: murder-and-manslaughter, crime, law-crime-and-justice, perth-6000, wa, united-states, australia

Robert Cock- QC- Former Director of the Director of prosecutions for Western Australia -last day-Departing DPP Robert Cock. (ABC)

Mallard prosecutor complaint passed on

14 Aug 2009,

https://www.abc.net.au/news/2009-08-14/mallard-prosecutor-complaint-passed-on/1390544

PHOTO: Ken Bates stood down last month with a lucrative payout.

The body that oversees complaints against lawyers has referred a complaint against a former prosecutor at the Director of Public Prosecutions (DPP) to an eastern states senior counsel.

Ken Bates was facing disciplinary proceedings for his role in the wrongful murder conviction of Andrew Mallard when he agreed to end his contract 19 months early.

He received a payout worth hundreds of thousands of dollars.

Correspondence, tabled in Parliament yesterday, revealed the Legal Practitioners Complaints Committee has referred aspects of a complaint against Mr Bates to a senior counsel in the eastern states.

The correspondence also revealed the former DPP, Robert Cock, wanted to negotiate an early end to Mr Bates' contract because he believed the disciplinary process was unlikely to be completed within two years.

The shadow Attorney-General, John Quigley (now Attorney General of Western Australia _2019/2020),

says the information calls into question Mr Cock's suitability for his new role as special counsel to the State Government.

Mr Quigley says the information reveals Mr Cock's desire to save the DPP from embarrassment by sacking Mr Bates.

"Mr Cock did not want the truth of what happened to Andrew Mallard to ever see the light of day. He should have stood Mr Bates' down years ago," he said.

He says he has advised Mr Mallard to seek the advice of an eastern states Queens Counsel (QC) over whether Mr Bates and the two police officers involved in his wrongful conviction should face criminal charges.

Mr Cock's employer, the Public Sector Commissioner Mal Wauchope, has been unavailable for comment.

Topics: law-crime-and-justice, government-and-politics, parliament, state-parliament, judges-and-legal-profession, wa, perth-airport-6105

First posted 14 Aug 2009,

Ken Bates stood down last month with a lucrative payout.

Mr John Quigley (now Attorney General of Western Australia _2019/2020)

says the information reveals Mr Cock's desire to save the DPP from embarrassment by sacking Mr Bates.

"Mr Cock did not want the truth of what happened to Andrew Mallard to ever see the light of day. He should have stood Mr Bates' down years ago," he said.

"Andrew Mallard death: A WA man’s 12-year fight for justice and freedom | The West Australian" https://thewest.com.au/news/

Andrew Mallard death: A WA man’s 12-year fight for justice and freedom

“I am an innocent man ... you have not heard the last of this.”

With those words, a then 33-year-old Andrew Mark Mallard was led from the dock of the Supreme Court in Perth towards a life sentence for a murder he did not commit.

It was far from the last the WA legal system would hear from this vulnerable “drifter”, who suffered from mental illness, and who had been wrongly convicted of murdering Mosman Park jewellery store owner Pamela Lawrence.

In fact, it was just the beginning. More than 10 years of legal appeals — during which sensational claims of withheld evidence, police corruption and bias in the judicial system and the media were aired — would follow before Mr Mallard would walk out of Casuarina Prison, exonerated.

Mr Mallard’s 12-year fight to clear his name, aided by his family and a high-profile team including then Labor MLA John Quigley, Malcolm McCusker and journalist Colleen Egan, would rock WA’s justice system.

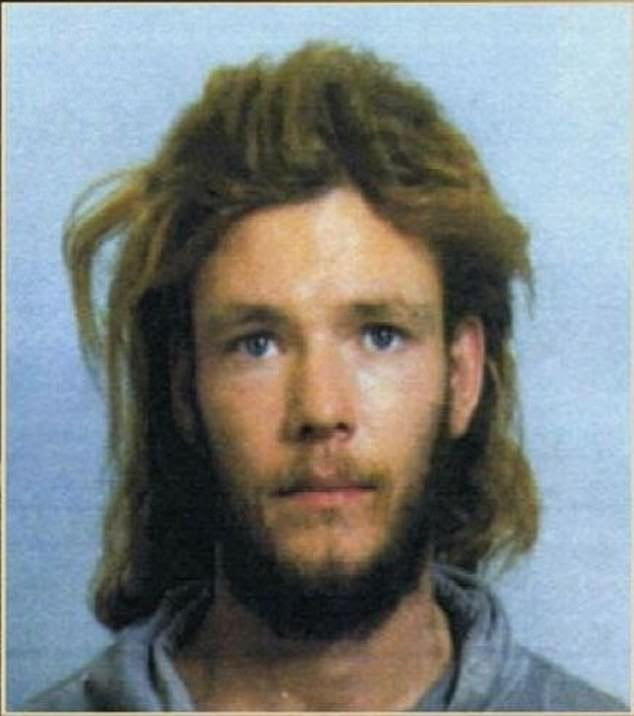

British-born Mr Mallard, who lived in Mosman Park, was a petty thief with a marijuana habit who was prone to telling far-fetched stories.

The day before Mrs Lawrence was found dead, Mr Mallard was charged over a burglary and impersonating a police officer, relating to a tale he spun in various forms which involved him being a police informant acting as an undercover drug agent.

Mr Mallard was also, according to a psychiatrist who later testified at his pre-trial hearing, in the manic stage of a bipolar mood disorder.

Pamela Lawrence, a wife and mother of two daughters, was a popular jeweller who established her business Flora Metallica on Glyde Street in 1973.

Her body was found by her husband Peter on May 23, 1994, in the midst of a huge storm which had swept across the western suburbs.

Police said Mrs Lawrence had been hit with an object at least 12 times. Their investigations led them to Graylands Hospital two days later, where Mr Mallard had been admitted after an unrelated minor court appearance.

Mr Mallard was interviewed a number of times, offering several different alibis. Later, he confessed to the killing and mentioned a potential murder weapon — a wrench — but then retracted it, claiming it was only his theory of what had happened.

Mr Mallard was charged with the wilful murder of Mrs Lawrence on July 19, 2004. He entered a plea of not guilty. In a Supreme Court trial which started on November 2, 1995, Mr Mallard was successfully prosecuted on the strength of his “confession” — unsigned, handwritten notes by police and a 20-minute videotaped interview on his theory as to what had happened.

During the trial he claimed detectives had fabricated parts of the interviews they related to the court, and had harassed, intimidated, beaten and threatened to shoot him as they interrogated him.

On November 15 a jury found Mr Mallard guilty. Five weeks later he was sentenced to life in jail, with a minimum of 20 years. In the moments after his son had proclaimed his innocence as he was led from the dock, Roy Mallard vowed outside court the family would not give up until their son and brother was exonerated.

“Andrew was convicted on unsigned and unseen statements written by the police,” he said. “There are so many holes in the case it’s not funny.”

So began the decade-long battle to free Mallard. His father would not live to see its conclusion, as he died from cancer in 1998, leaving his wife Grace and daughter Jacqui to continue the fight. They endured setback after setback, including an unsuccessful appeal to the Court of Criminal Appeal in 1996 and a failed High Court bid the year after.

A breakthrough finally came in 2002 when a new team of volunteers — led by Mr Quigley, now WA’s Attorney-General, Mr McCusker and Egan — served a petition to then attorney-general Jim McGinty, asking that the case be again referred to the Court of Criminal Appeal.

The petition contained new forensic evidence which was not disclosed in the trial — testing done by a forensic pathologist which found it was not possible for Mrs Lawrence’s wounds to have been caused by the wrench Mr Mallard described as the murder weapon.

It was also found police had not disclosed all witness statements to the defence and had retyped some statements to exclude matters favourable to Mr Mallard.

Mr McGinty agreed, but the Mallards’ joy was short-lived. The Court of Criminal Appeal rejected the bid. The group persevered and lodged an appeal to the High Court in 2003. Almost two years later, Mr Mallard’s conviction was quashed in a 5-0 judgment. Three months later, on February 20, 2006, Mr Mallard, 43, finally walked free from prison after 12 years.

Accompanied by his mother and sister, Mr Mallard said he was looking forward to a good night’s sleep without the rattle of guards’ keys to keep him awake.

He still had the threat of a retrial hanging over him but that disappeared when a new suspect emerged in May of that year. It was revealed convicted murderer Simon Rochford’s palm print had been found in Mrs Lawrence’s store, but before any investigation could proceed Rochford was found dead, of apparent suicide, in Albany Prison the next day.

It would be another three years — during which a Corruption and Crime Commission inquiry delivered misconduct findings against two police assistant commissioners and a senior prosecutor — before the Mallard case drew to a close. A decade ago, on May 5, 2009, the State Government offered Mr Mallard a $3.25 million ex gratia payment.

He pledged to spend it on his mother and sister and rebuilding his life. “I want to be like everybody else. I want to have a wife and a family and to provide for my family through my own efforts,” he said.

"Australian Andrew Mallard's last call to family revealed before death in LA hit and run" https://www.dailymail.co.uk/

'He said he was getting married, that he'd met a girl': Revealed - the heartbreaking last phone call of Australian man who died in a hit-and-run after being jailed for 12 YEARS over murder he didn't commit

By Kylie Stevens and Kelsey Wilkie For Daily Mail Australia13:53 27 May 2019, updated 14:29 27 May 2019

- Friends have recalled their shock to news of the tragic death of Andrew Mallard

- Killed in a hit and run in Los Angeles last month, 13 years after freed from prison

- Wrongly spent 12 years behind bars for the 1994 murder of Pamela Lawrence

- Had called his family the night before his death to say he was getting married

An innocent man who spent 12 years behind bars for a murder he didn't commit had called his family to say he had fallen in love the night before his life was abruptly cut short in a hit-and-run in Los Angeles.

Australian Andrew Mallard, 56, was tragically killed after he was struck by a car while crossing a road at Sunset Boulevard and Formosa Avenue in Hollywood last month.

He was found guilty of killing Perth jeweller Pamela Lawrence in 1994 in one Australia's worst miscarriages of justice.

He spent more than a decade in jail before his conviction was quashed in the High Court in 2005, which saw him to be released the following year.

WA Attorney-General John Quigley and journalist Colleen Egan, who played an integral role in overturning Mr Mallard's conviction, have recalled their shock to the news of his recent death.

Andrew Mallard endured one of Australia's worst miscarriages of justice before his life was tragically cut short in a hit and run crash in April

Andrew Mallard endured one of Australia's worst miscarriages of justice before his life was tragically cut short in a hit and run crash in April

'He had called them just the night before and said he was getting married, that he'd met a girl and that he was totally in love. They are obviously very devastated. Grace (his mother) is 92 years old now,' Ms Egan told ABC's Australian Story.

Mr Quigley described him as gentle man and honest person.

'I can't tell the feeling of grief that washed over me. I held that man in my arms in prison and promised I'd never leave him. I felt just a little bit of me die when I heard this news,' he said.

'I just think it's so unfair, so sad, what happened. I'd like to think that Andrew's soul is resting in peace.'

Friend Tonina Khamis expressed her disbelief to the news revealed he had recently written to her to say he was well and happy.

'I'm still processing it, and I'm thinking, well, maybe the universe had other plans for him. Maybe the grass is now greener on the other side for him,' she said.

Journalist and author Colleen Egan (pictured) was woken by the tragic news that Andrew Mallard, the man she helped be released from prison had been killed in a hit and run

Journalist and author Colleen Egan (pictured) was woken by the tragic news that Andrew Mallard, the man she helped be released from prison had been killed in a hit and run

The episode also aired parts of its 2010 interview with Mr Mallard.

'I was wrongfully imprisoned. There's a stigma that goes with that and it still goes with that,' he told Australian Story nine years ago.

'I still get abuse from certain members of the public. I still get scoffed at. People don't know the full story. They think I'm some sort of psycho, some sort of mentally ill patient.

'I had done nothing wrong. I was innocent and I protested my innocence from the word go. For nearly 11.5, nearly 12 years, For nearly 11.5, nearly 12 years, I was protesting my innocence consistently, continually.'

Monday night's episode ended with a statement from Pamela Lawrence's family to say they were shocked and deeply saddened by Mr Mallard's death.

They added their only solace was that he regained his freedom and saw his name cleared.

'We had high-profile people from the police and the prosecution that were still confident they had the right person,' Ms Lawrence's daughter Katie told the program in 2010.

'It didn't occur to us that... ..the justice system could have failed so dismally.'

CCTV footage captured the heartbreaking moment Mr Mallard was struck by a silver sedan in Los Angeles.

In the footage Mallard can be seen casually strolling across the road at Sunset Boulevard and Formosa Avenue in Hollywood, near where his fianceé lives.

The footage shows Mallard suddenly stopping as the vehicle, with its headlights on, approaches.

The sedan does not slow down as it ploughs threw Mallard before fleeing east on Sunset Boulevard.

Dozens of onlookers can then be seen rushing to his rescue before he died at the scene.

Kristopher Smith, 19 was charged several days later with felony hit and run involving injury or death and had bail set at $A71,300.

'I panicked,' Smith told LA TV station CBS2.

'I just went home to my mum.'

Smith says he did not see Mr Mallard as the Australian walked across busy Sunset Blvd.

He added he was 'sorry for the accident' and he felt 'sorry for the victim's family'.

Mr Mallard's family has been left devastated by his tragic passing.

'He suffered injustice and spent almost 12 years in prison for something he didn't do,' his sister Jacqui Mallard told The Australian last month.

'Those years were taken from him and now his life has been taken. We are heartbroken.'

Andrew Mallard featured on Australian Story in 2010, four years after he was released

Andrew Mallard featured on Australian Story in 2010, four years after he was released

Mr Mallard was free for only 13 years after being cleared of murder.

Pamela Lawrence, a business owner in Mosman Park, Perth, was attacked at her jewellery shop on the afternoon of Monday, 23 May 1994.

She was attacked sometime between 3pm and 6pm and died in an ambulance at 7pm.

Mr Mallard quickly became a suspect because a witness saw a man matching his description outside the shop.

He had been released from police custody earlier that day after being arrested for breaking into his his girlfriend's ex-boyfriend's apartment and was seen arriving in Mosman Park in a taxi at around 5pm.

Mallard had a history of mental illness but no history of violence. There was also no weapon, blood or DNA connecting him to the case.

Two key pieces of evidence led to his conviction – the first was police notes from interviews with Mallard where it was claimed Mallard had confessed.

The second was 12 minutes of an 11-hour interview where Mallard was filmed speculating how Ms Lawrence may have been killed.

'If Pamela Lawrence was locking the store up, maybe she came in through the back way, the front door was already locked… Maybe she left the key in the back door and that's why he had easy access, and that's why she didn't hear him until he was… in the store,' he told police.

Mallard spent 12 years of his life sentence at Casuarina Prison in Perth before he was released in 2006.

Months later a cold-case review found a palm print linking English backpacker Simon Rochford to the crime scene.

The convicted murderer was serving a 15 year minimum sentence for bashing his girlfriend Brigitta Dickens to death.

Simon Rochford (pictured) was later linked to the crime scene of Pamela Lawrence's murder in 1994. He committed suicide in a Western Australian jail days after he was interviewed by police

Simon Rochford (pictured) was later linked to the crime scene of Pamela Lawrence's murder in 1994. He committed suicide in a Western Australian jail days after he was interviewed by police

He had four years left on his sentence when he was questioned by police in relation to mother-of-two Ms Lawrence's death.

A week later he committed suicide in a West Australian prison after being publicly named as the new suspect for Ms Lawrence's murder.

The following year, in 2007, a Corruption and Crime Commission inquiry found that police had withheld crucial information from Mallard's defence team, including details of an undercover operation.

It also emerged that two police officers had caused witnesses to alter their statements.

Mallard was granted a $3.25million compensation payment for his time behind bars after lengthy negations with the state government in 2009.

He later moved to the United Kingdom, while also spending time in America.

Andrew Mallard's case: A timeline

1994: Perth jeweller Pamela Lawrence is brutally killed with a heavy instrument in her own store. The murder weapon has never been found

1995: Andrew Mallard is wrongly convicted of her murder

1996: Mallard's appeal to the Supreme Court of Western Australia is dismissed

2003: After spending eight years of his sentence of life imprisonment in strict security, he petitioned for clemency

The Attorney-General for Western Australia referred the petition to the Court of Criminal Appeal, which later dismissed the appeal

2005: Mallard's appeal is heard in the High Court, his conviction is quashed

2006: After 12 years behind bars, Mallard is free

A cold case review is held and uncovers a partial palm print linking British backpacker and convicted murder Simon Rochford to the crime scene

A week after Rochford is questioned by police, he is found dead in his prison cell from suspected suicide

2007: A Corruption and Crime Commission investigation into the case leads to two assistant police commissioners, Mal Shervill and David Caporn, being forced to step down

2009: Mallard is granted a $3.25 million ex gratia payment for his time behind bars

2019: Mallard is killed in a tragic hit and run in Los Angeles

On completing his fine arts degree at Curtin University, Mr Mallard left WA for Britain, where he planned to continue his studies, in August 2010. It appears he had finally found the happiness he sought when his life was tragically cut short this week.

The Wronged Man: Andrew Mallard

https://www.abc.net.au/austory/the-wronged-man:-andrew-mallard/11121148

Introduced by Western Australia's Attorney-General John Quigley

When Pamela Lawrence was brutally murdered in her Perth shop in 1994 police focused their investigation around one suspect, Andrew Mallard.

He quickly became the victim of a miscarriage of justice, spending twelve years in jail for a crime he didn’t commit.

Mallard’s family fought successfully to release him, enlisting then WA Shadow Attorney-General John Quigley and journalist Colleen Egan who uncovered a trail of deception and police misconduct.

In this updated episode of Andrew Mallard’s story, Australian Story talks to the friends who stood by him until his untimely death last month.

INTRODUCTION: Hello.I’m John Quigley, the Attorney- General for Western Australia. Twenty five years ago a much loved woman was brutally murdered. It led to one of the most disgraceful events in WA’s legal history, an event that I became intimately involved in. Andrew Mallard was wrongfully convicted of the crime and spent 12 years in prison before being exonerated and compensated. Andrew told his story on this program nine years ago, tonight the final chapter.

ANDREW MALLARD: I was wrongfully imprisoned. There’s a stigma that goes with that and still goes with that. I still get abuse from certain members of the public. I still get scoffed at et cetera. People don’t know the full story. They think I’m some sort of psycho, some sort of mentally ill patient. I had done nothing wrong. I was innocent and I protested my innocence from the word ‘go’. For near eleven and a half - nearly 12 years, I was protesting my innocence consistently, continually, because it was the truth!

TONINA KHAMIS, FRIEND: He would often tell me that he never resolved his anger. He was always angry about the police and the prosecutors that brought the injustice.

COLLEEN EGAN, JOURNALIST AND AUTHOR: Andrew was probably not for this planet. I mean the bad luck that he had. He was just not a soul that belonged here in some ways

JOHN QUIGLEY, WA ATTORNEY GENERAL: The Greeks talk about the goddess Clotho who spins people’s fate. Clotho was spinning against Andrew from the get go.This whole story is like some Greek tragedy the audience think this is going well then it all just turns to mud

COLLEEN EGAN, JOURNALIST AND AUTHOR: It was about five o’clock in the afternoon and that day was the day of a big freak storm. Everyone in Perth remembered it for this terrible weather that suddenly came in. Shops were closing up around Glyde Street in Mosman Park where Pamela Lawrence had a little jewellery store. Pamela’s husband, Peter Lawrence went down to the shop and realized that she had been bludgeoned in a very, very violent attack.

KATIE KINGDON, Pamela Lawrence’s daughter: And the paramedics brought mum out of the shop on a stretcher and into the back of the ambulance. I saw her. She was just bandaged and her face looked beautiful as usual, she was just in a jumper and jeans and she just looked like she was asleep with a bandage round her head. When I got home I called the hospital and the nurse that answered the phone said to me that they’d stopped CPR because they couldn’t do anything. And then I had to go and tell my sister which was probably the worst moment of my life.

COLLEEN EGAN, JOURNALIST AND AUTHOR: Understandably there was a very big manhunt that went on immediately for who may have killed this woman who didn’t seem to have an enemy in the world. There was 136 initially on the suspect list, because someone had seen someone in the window, a man and there was an identikit description put out, and so the police amassed a large number of suspects and Andrew Mallard was one of those suspects.

ANDREW MALLARD: I was down on my luck, I was vulnerable, I was living on the streets, I was trying to survive. I was suffering from a nervous breakdown basically and I was so embarrassed by the situation that I didn't want to approach my family for help, so I tried to make it on my own.

GRACE MALLARD, MOTHER: He hadn’t been eating. He’d been smoking pot and living rough. I mean he just was not normal at that time. Not what you’d call stable anyway. He wasn’t stable.

COLLEEN EGAN, JOURNALIST AND AUTHOR: It’s not difficult to see how Andrew became a suspect in the first place. He’d had a bit of a mental breakdown. He was acting quite erratically and ended up in Graylands Psychiatric Hospital as a result of some things he was doing including some sort of petty crime and thievery and one occasion where he pretended to be a police officer and broke into a flat

JOHN QUIGLEY, WA ATTORNEY GENERAL: So he went in for 21 days. But whilst in hospital he was then interviewed by the police. He was not offered the public advocate or anyone from Legal Aid. Or indeed he didn’t even have a mental health nurse with him. You’re asking a mental patient in a psychotic condition as to his exact movements at a specific time some two or three weeks before. So over a period of two or three days they excluded what Andrew was putting forward as alibi evidence and then came back and said "You're a liar".

COLLEEN EGAN, JOURNALIST AND AUTHOR: After Andrew was released from the psychiatric institution, within hours of his release from there, he was put straight into a police interview room with Detective Caporn and he was there for eight hours,

ANDREW MALLARD: At that point I knew he was looking at me as the murderer. And this is when I started to protest my innocence. I said, ‘Look I’ve had nothing to do with that I’ve had nothing to do with that murder. I’m innocent.’

COLLEEN EGAN, JOURNALIST AND AUTHOR: None of that was recorded and out they came saying we have got a confession. It always seemed strange that while they said he confessed during that first 8 hour period they let him out on the street

ANDREW MALLARD: And during that week of brief, confused, dazed freedom, I am approached by a man introducing himself as Gary. Gary was actually I now know, an undercover officer.

JOHN QUIGLEY, WA ATTORNEY GENERAL: The undercover officer took Andrew about Fremantle, bought him hotel rooms, bought him alcohol, supplied him with a bong and on Andrew's account, cannabis.

COLLEEN EGAN, JOURNALIST AND AUTHOR: He was really fuelling this mania.When they brought him back a week later into the same interview room, sat there for another couple of hours with him and then decided to put him on video.

EXTRACTS POLICE INTERVIEW

OFFICER: We brought you in this morning and we had a conversation in relation to the murder of Pamela Lawrence at Mosman Park. Do you agree with that?

ANDREW MALLARD: I do.

ANDREW MALLARD: I had over the course of my life suffered from a behavioural situation where I was I would always acquiesce. I would try to please people. I was a people pleaser.

OFFICER: And you told us that you went in the rear went through the rear of the shop at Flora Metallica. Is that what you told us?

ANDREW MALLARD: I told you that.

OFFICER:Okay, okay. I’m just going to go through that now okay – what you told us. We’ll sort the rest out later. Okay?

COLLEEN EGAN JOURNALIST AND AUTHOR: And they were just very leading questions from the detective trying to get Andrew to agree with things that he was saying and really so much of it just was clearly theorising.

OFFICER: You described the steps to us and you described the rear door and the flyscreen door.

ANDREW MALLARD: I did. May I say something else?

OFFICER: Okay, yeah. Go on.

ANDREW MALLARD: If Pamela Lawrence was locking the store up, maybe she came in through the back way and the front door was already locked and she left the key in the back door, and that's why he had easy access and that's why she didn't hear him until he was

OFFICER: We'll go on with what you told us earlier ok before we go into anything else,

COLLEEN EGAN: We found out that a lot of the information that he was giving in that video interview and in earlier interviews was information fed to him by the undercover officer and fed to him by the detectives that were interviewing him.

OFFICER: the fact is that you told us all these things and you now say that that was a complete pack of lies, that all the things that you told us was

ANDREW MALLARD: I say that is my version, my conjecture of the scene of the crime.

OFFICER: Ok no worries. We’ll leave it at that. End of story. Thanks very much.

GRACE MALLARD, MOTHER: The next thing we knew we had a telephone call from a policeman to say they’d arrested Andrew for murder.

NEWS REPORT: Today a breakthrough Cop:Major crime squad have today charged Andrew Mark Mallard thirty one years of age with the wilful murder of Pamela Suzanne Lawrence

I couldn't believe it. You know? Andrew? Andrew's not violent. He's not a violent person, never was. He was a very gentle type of person. And you know, it just floored us.

KATIE KINGDON, PAMELA LAWRENCE'S DAUGHTER: Dad and Amy and I attended most of the trial. Ken Bates, the prosecutor, set my family at ease. He was confident that they had the right person.

COLLEEN EGAN, JOURNALIST AND AUTHOR: The whole of the case was based on these so‑called confessions.

NEWS REPORT: The jury heard that although Mallard had twice confessed to the murder but had later retracted those confessions, there were 15 things he’d told police that only the killer would have known.

COLLEEN EGAN, JOURNALIST AND AUTHOR: There was no DNA, there were no fingerprints, there was no blood, despite this being a horrendously bloody scene, there was nothing forensically at all.The most damning single piece of evidence against Andrew at trial and when he was later trying to get his convictions overturned was this Sidchrome wrench drawing that he'd done during the unrecorded part of the police interview. We now know, having heard the body wire tapes of Gary the undercover officer that Sidchrome and the wrench was all discussed during that undercover operation that we never knew anything about. And the prosecutor said "With this wrench he killed her" and Andrew was quickly convicted.

NEWS REPORT: “Mallard, 33, continued to protest his innocence throughout the sentencing hearing frequently interjecting. Outside the court, Mallard’s father also protested his son’s innocence.”

ROY MALLARD, FATHER: “We know my son Andrew is innocent of this terrible crime. The real murderer is still free.

CAPTION:

Andrew Mallard was sentenced to 20 years in jail in 1995.

Appeals to the WA Supreme Court and the High Court failed.

His family fought on.

COLLEEN EGANN, JOURNALIST AND AUTHOR: I got a phone call one day from Grace Mallard. And as a last resort I suppose, they came to me working as a journalist to try and investigate the case and find fresh evidence. When I was reading the transcript I really couldn't believe that anyone could be convicted on the evidence that Andrew was convicted on. In 2002, I’d already been looking at this case for four years. Andrew was getting quite desperate.I was working as a political journalist and in my former life as a court reporter, John Quigley was one of the best‑known and smartest lawyers in town and John Quigley had joined with the Labor Party, the backbench of the government

JOHN QUIGLEY, WA Attorney-General: I had for about 25 or 30 years been the counsel of choice for the Western Australian Police Union in Perth